[Editor’s note: the post below appears today on the front page of The Huffington Post.]

By Govindini Murty. As we celebrate the holidays, many of us are taking digital photos and videos of our loved ones, thinking that these digital files will be saved forever. The same thinking applies to our movies, books, songs, and stories – we save all of our creative works to the digital cloud, assuming they will be safely stored there. But between continual tech upgrades that make our digital files obsolete, and UN agencies that now seek to censor the internet, the question must be asked: are any of our cultural memories really safe in the digital age?

Recent developments are making it clear that control of digital information, and in particular of online artistic content, is the new front in the twenty-first century war of ideas. The UN’s International Telecommunications Union recently voted to allow individual nations to censor the free flow of the internet. This move was welcomed by authoritarian governments like China, Iran, Saudi Arabia, and Russia – and condemned by democracies like the U.S., the U.K., Canada, and Australia.

Combine this alarming development with the fact that many people now store their photos, videos, writing, and other creative works in online clouds, without ever creating hard copies or backing up their data – and the result is the potentially explosive ability of authoritarian forces to erase vast areas of our cultural memory at the push of a button. Without physical copies, no longer does a dictator have to go to the trouble of staging public burnings of art and books, as in 1930s Nazi Germany or 15th century Florence under Savonarola.

The freedom of the individual artist to speak out is more important now than ever, as today’s authoritarian nations seek to silence artists at every opportunity. Russia’s jailing of the women’s punk rock group Pussy Riot, China’s jailing of dissident artist Ai Weiwei, and Iran’s jailing of filmmaker Jafar Panahi are all examples of modern autocracies crushing citizens’ rights to creative expression. Apparently nothing is more threatening to today’s political fanatics than a free, creative individual.

And now the UN is going to give these authoritarian nations official sanction to censor the online work of artists, filmmakers, writers, and creative thinkers. This is a worldwide cultural catastrophe in the making.

Yet this isn’t the only danger that faces the preservation of our cultural memories; a new form of techno-utopianism poses a serious challenge to the preservation of our creative works. The problem in technologically advanced cultures like America is that we sometimes value technology for its own sake more than we do content. We equate advanced technology with greater value, so we rush to upgrade software, devices and formats without making any corresponding effort to ensure that prior digital files and formats can still be used.

Obviously it’s important that we progress technologically. As a filmmaker I embrace digital filmmaking tools for their ability to democratize the movies, and as a writer I wouldn’t even be writing this post if it weren’t for the freedom of speech enabled by the internet. But as the digital revolution matures, we must give thought to how we manage and protect the enormous new quantity of digitally-created works.

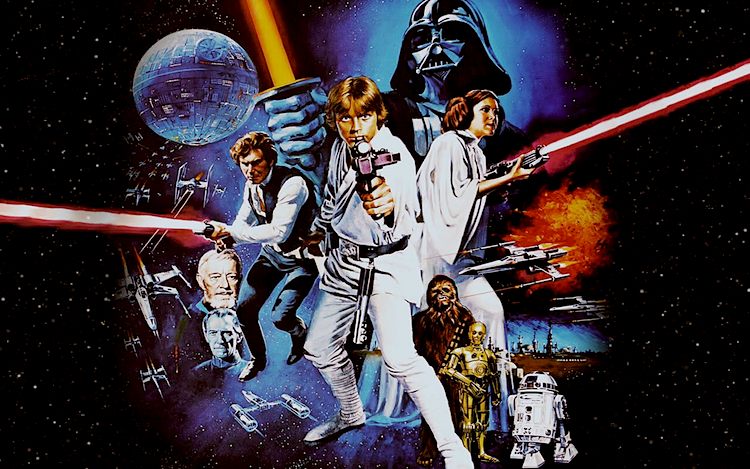

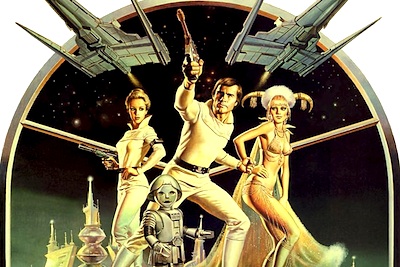

This holiday season we’re celebrating blockbuster movies like Les Misérables and The Hobbit, but the irony is that these films are based on classic novels by Victor Hugo and J.R.R. Tolkien that were written in the pre-digital age – and are still around today because they’ve been widely distributed in paper hard copies. But what about fresh artistic and literary works created today? Where will they be fifty or a hundred years from now if they only exist in digital form? Even if they are classics, who will have the chance to adapt them into tomorrow’s movies or other, future forms of storytelling if they are erased within a few years by government censors – or are unreadable because tech companies have upgraded tablets/e-readers to the point that they can’t read prior digital books? Continue reading LFM’s Govindini Murty at The Huffington Post: This Holiday Season, What Happens When All of Our Cultural Memories Go Digital?