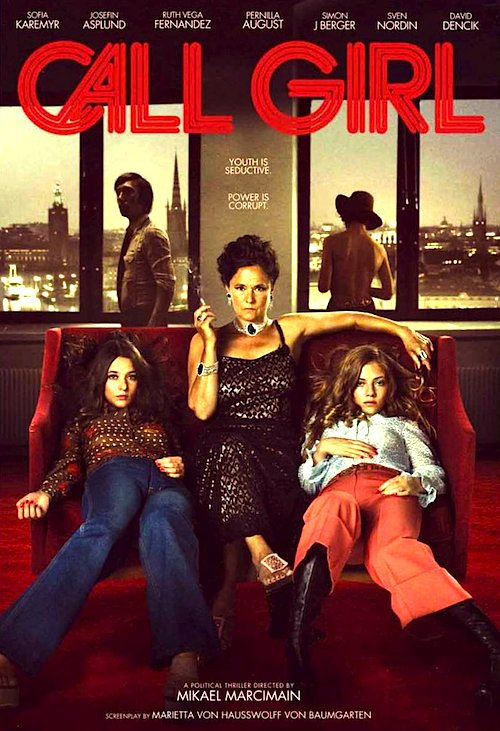

By Joe Bendel. The 1970’s really were swinging for Sweden, especially for the government. At the time, Olof Palme’s Minister of Justice, Lennart Geijer, was pushing a measure to largely emasculate laws against pedophilia, until he was caught up in the prostitution scandal that would subsequently carry his name. As it happens, under-aged girls were involved. It was a sordid but bipartisan national scandal that makes great fodder for Mikael Marcimain’s real life political thriller Call Girl, which screens as a selection of Film Comment Selects 2013.

Mere days before what is expected to be a close election, an American actress suspiciously resembling Jane Fonda sings the praises of the progressive PM never specifically identified as Palme on television. Meanwhile, crusading vice cop John Sandberg types his report with a purpose. At every step, the state security service has interfered with his investigation, as viewers soon learn via flashback.

Iris Dahl is too much for her mother to handle, assuming she ever tried. Fortunately, in liberal Sweden she can simply deposit her problem child in a juvenile home that looks more like a hippy commune. Sneaking out is a snap, especially when her cousin Sonja Hansson arrives to mutually reinforce their delinquency. Unfortunately, in the course of their partying, they encounter Dagmar Glans. A madam with a powerful clientele, Glans recruits the fourteen year-old girls for her stable.

At first, the cousins are seduced by the easy money and flashy lifestyle Glans provides. Inevitably though, the work takes a toll on them, physically and emotionally. Any ideas they might have about quitting are quickly dispelled by the procurer and her enforcer, Glenn. After all, the girls could recognize some rather powerful politicians. Initially, Sandberg is oblivious to Glans’ young working girls and the notoriety of her clients. He is simply trying to bust a vice queen with apparent connections. However, when his wiretaps come in with conspicuous gaps, Sandberg and his hours-from-retirement partner start to suspect the scope of the conspiracy afoot.

At first, the cousins are seduced by the easy money and flashy lifestyle Glans provides. Inevitably though, the work takes a toll on them, physically and emotionally. Any ideas they might have about quitting are quickly dispelled by the procurer and her enforcer, Glenn. After all, the girls could recognize some rather powerful politicians. Initially, Sandberg is oblivious to Glans’ young working girls and the notoriety of her clients. He is simply trying to bust a vice queen with apparent connections. However, when his wiretaps come in with conspicuous gaps, Sandberg and his hours-from-retirement partner start to suspect the scope of the conspiracy afoot.

Call Girl resembles a 1970’s film in more ways than just soundtrack and décor. In an icily detached manner, it presents a deeply cynical view of the Swedish government, definitely including St. Olof’s administration. Nor does it take leering pleasure from Glans’ dirty business. Marcimain leaves little doubt Dahl and Hansson are grossly exploited by just about everyone – and the state social welfare establishment simply looked the other way, for fear of “stigmatizing” them. We even witness a strategy session for Geijer’s proposal to effectively normalize sexual relations with minors.

With credits including television miniseries and second unit work on Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy, Marcimain was well prepared to tell an intricately plotted, richly detailed, multi-character tale of intrigue. Despite the very specifically Swedish circumstances, it is always easy to follow. Somehow he also clearly conveys the unsavory acts the cousins are forced to participate in, without reveling in the luridness.

Frighteningly seductive in a weird, matronly way, Pernilla August’s Glans vividly shows how the devious exploit others and insinuate themselves with the powerful. It is a big, bravura portrayal of a user. As the used, Sofia Karemyr is shockingly powerful portraying Dahl’s wilted innocence. Risking type-casting (having appeared as Machiavellian game-players in A Royal Affair and Tinker Tailor), Danish-Swedish actor David Dencik again turns up as government fixer, Aspen Thorin.

Call Girl is a great period production that never romanticizes its era. Smart, tense, and unexpectedly pointed in its critique of the Swedish justice system, Call Girl is highly recommended for fans of complex political drama. It screens this today (2/20) and tomorrow (2/21) at the Howard Gilman Theater as part of Film Comment Selects 2013.

LFM GRADE: A-

Posted on February 20th, 2013 at 1:17pm.