By Joe Bendel. The worst crimes are always committed by altruists, but Ana Puttnam knows her oncologist father is different. She has returned to his home town in hopes of restoring his reputation while he is still alive. However, something or someone in their ancestral home begs to differ in Roberto Busó-García’s supernatural drama The Condemned (trailer here), which opens this Friday in New York.

By Joe Bendel. The worst crimes are always committed by altruists, but Ana Puttnam knows her oncologist father is different. She has returned to his home town in hopes of restoring his reputation while he is still alive. However, something or someone in their ancestral home begs to differ in Roberto Busó-García’s supernatural drama The Condemned (trailer here), which opens this Friday in New York.

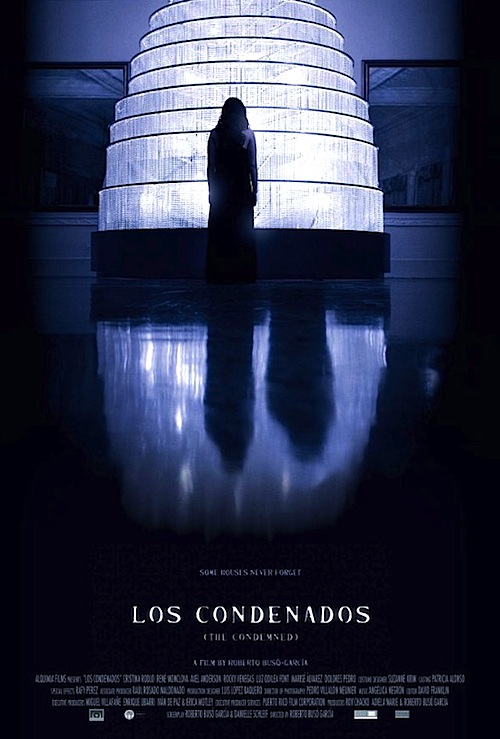

Largely incapacitated, Dr. Puttnam (with two t’s) is not long for this earth. His daughter has brought him back to their stately manor house in Rosales, Puerto Rico – where it all began – to establish a museum dedicated to his philanthropic work. It was here that he established his first free cancer clinic for the poor. However, he has also been dogged by scandalous rumors regarding his early career. She was hoping the villagers would rally to his defense, but nobody seems to want to get involved. As she presses on, strange things start happening in the house. The planned exhibitions are a particular focus of the mysterious venting.

Only two people in Rosales are happy to see the Puttnams return. One is the loyal family retainer Cipriano. The other is the new chauffeur, the one villager willing to present himself for prospective employment. Each has their reasons for their interest in the Puttnam family. Likewise, they are both uneasy with Ana’s plans to revive the family’s big Christmas soiree for the townsfolk. At least she will get some use out of her mother’s old crystal chandelier tree.

It is hard to decide whether The Condemned is really intended as horror film or more of an uncanny morality tale. There is one gruesome death, but it is rather out of place, leading one to wonder if it was a cast-member request Busó-García obliged. Aside from a handful of shocking moments, it is more about creeping dread and the corrupting influence of the past on the present—almost more Tennessee Williams than H.P. Lovecraft.

Still, Busó-García and production designer Suzanne Krim’s team crafted quite a gothic setting. That chandelier tree becomes the indelible image of the film, but the rest of the house is quite atmospheric too. Frankly, Busó-García’s deliberate genre coyness deftly keeps viewers off-balance and unlikely to anticipate the third act revelation.

Poised and photogenic, Cristina Rodlo is surprisingly engaging as Ana Puttnam, completely avoiding any scream queen theatrics or manipulations. Her work holds up, even as the audience’s perspective shifts. Popular Puerto Rican comic actor René Monclova is also suitably earnest yet appropriately mysterious as Cipriano.

Visually, one can see the influence of the Spanish horror movie renaissance on The Condemned, but Busó-García tells his tale with restraint. While it is certainly slow by the genre standards that may or may not apply, it all more or less comes together at the end. Recommended for those who enjoy their paranormal fare on the cerebral side, The Condemned opens this Friday (3/1) in New York at the Quad Cinema.

LFM GRADE: B

Posted on February 25th, 2013 at 2:17pm.