By David Ross. Documentary film seems to shift between nature puffery with a rueful environmental subtext, vaguely condescending anthropological examinations of red state weirdos, and aggressive leftwing political polemics. As usual, conservatives have ceded the field without much of a fight. I am not in favor of conservatives answering leftwing polemics with rightwing polemics. I am in favor of conservatives answering clichés with non-clichés, answering tendentious narratives with non-tendentious narratives. With this mind – and with the caveat that my documentary viewing has been far from encyclopedic over the last ten years – let me offer my list of the decade’s best documentaries. Please note that ‘best’ in this case is a cinematic assessment; it has nothing to do with political point of view.

By David Ross. Documentary film seems to shift between nature puffery with a rueful environmental subtext, vaguely condescending anthropological examinations of red state weirdos, and aggressive leftwing political polemics. As usual, conservatives have ceded the field without much of a fight. I am not in favor of conservatives answering leftwing polemics with rightwing polemics. I am in favor of conservatives answering clichés with non-clichés, answering tendentious narratives with non-tendentious narratives. With this mind – and with the caveat that my documentary viewing has been far from encyclopedic over the last ten years – let me offer my list of the decade’s best documentaries. Please note that ‘best’ in this case is a cinematic assessment; it has nothing to do with political point of view.

• Jazz (2000, Ken Burns).

• Mark Twain (2000, Ken Burns).

• Dogtown and Z-Boys (2002) is the surprisingly interesting story of the birth of skateboarding. You will come to view the annoying punks who nearly run you down on the sidewalk with a new respect.

• Stone Reader (2002) chronicles the search for the forgotten novelist Robert Stone.

• The Art of Piano: Great Pianists of the 20th Century (2002) is like a Pharaonic tomb in its wealth of archival footage: Horowitz upon his return to Carnegie Hall in 1965, Rubinstein in Moscow, etc.

• The Kid Stays in the Picture (2002, Robert Evans) is a lubricious exercise in autobiographical self-indulgence from film producer Robert Evans, a live wire even by Hollywood standards.

• Architectures (2003), a four-disc series, presents case studies in modern architecture, each about twenty-five minutes long. Much of the architecture is rebarbative, and the film itself may be a bit dry and technical for some tastes, but few films about art and culture are this detailed and intellectually serious.

• Deep Blue (2005) is underwater cinema at its most lush and exotic. The inevitable environmental message sneaks in at the end, but one can’t really call it gratuitous.

• Deep Blue (2005) is underwater cinema at its most lush and exotic. The inevitable environmental message sneaks in at the end, but one can’t really call it gratuitous.

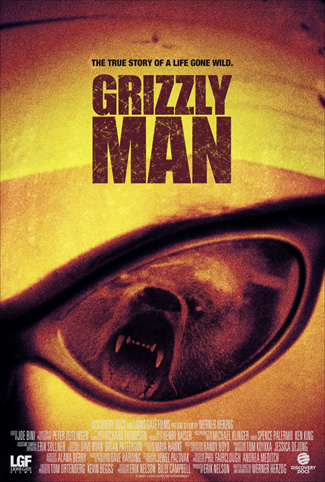

• Grizzly Man (2005, Werner Herzog). Nutcase lives with the bears and gets eaten

– go figure. Even so, the film provides a compelling critique of a certain kind of romantic idealization of nature, which poses dangers for us all.

• Ballets Russes (2005) is a moving history of one of the twentieth century’s great ballet companies, featuring interviews with many of the dancers who made the company legendary. The film becomes an examination of – and finally a paean to – artistic dedication of the highest order.

• Into Great Silence (2005) is at once silent, static, and epic, a grand glimpse of life in a Carthusian monastery in the mountains of France. It is one of the more difficult and beautiful films ever made, and perhaps film’s most sincere and respectful attempt to portray the life of religious devotion.

• Encounters at the End of the World (2007, Werner Herzog) brings the Werneresque hermeneutical apparatus to bear on the McMurdo research station at the South Pole, with reflections on the soullessness of technology and the fate of humanity. This sounds deep – and in fact it is deep.

• Note by Note: The Making of Steinway L1037 (2007, Ben Niles) chronicles the construction of a Steinway grand piano, from lumber yard to Carnegie Hall. It is fascinating study of engineering expertise, but even more an homage to old-fashioned ideals of hand-craftsmanship. I plan to show it to my writing students, in the hope that its implicit ethic of perfectionism will teach them a lesson.

• Ballerina (2009, Bertrand Normand) chronicles the trials and triumphs of a gaggle of Kirov ballerinas at different phases in their careers. Among the featured dancers is Svetlana Zakharova, perhaps the greatest ballerina of her generation, and not incidentally one of the most beautiful women in the world. Here she is: ethereal in Swan Lake; sultry in La Bayadère; smoldering in Carmen.

Here’s an instructive documentary double-bill: The Kid Stays in the Picture and Derrida (about the French literary theorist and progenitor of deconstruction). Evans is charming, scabrous, lewd, and hilarious; Derrida is evasive and more spiritually sterile than imaginably possible. Sure, you’d rather have a beer with Evans, but with whom would you rather discuss Proust or Heidegger? I’m tempted to say Evans again. Derrida may be a genius in the strict sense, but he is a guarded genius. Personality, one realizes, is not incidental to genius; it may even be the essence of true genius.

If I had to give a decadal Academy Award, I would be deeply torn between Encounters at the End of the World, Note by Note, and Into Great Silence. The first is a film of intellect; the second a film of heart; the third a film of spirit. The latter must take the laurels, if only because its beauty is so unusual, its method so simple and yet so ambitious. Nearly three hours long, the film does not merely depict the lives of the monks, but attempts to induce in the viewer a sense of the monastic rhythm, the slowness and ceaselessness of the monks’ simple acts of toil and devotion. There seems to me a deep and central question in this, having nothing to do with matters of faith and observance. Breadth and depth exist always in opposition. Our culture has become a veritable cult of breadth, a crab-dance of scuttling lateral movement. The web is world-wide, but what remains world-deep?

Posted on August 31st, 2010 at 9:33am.