[Editor’s note: this is the first of a new LFM series of ‘visual essays’ for classic movie fans, called “Classic Cinema Obsession” by Jennifer Baldwin.]

By Jennifer Baldwin.

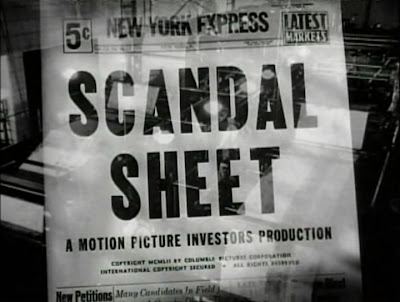

This Week’s Classic Cinema Obsession: SCANDAL SHEET (Phil Karlson, 1952)

Why do so many old movie obsessives (myself included) love Film Noir? Maybe it’s because so many films noir feature characters who are also, one way or another, obsessives themselves. Obsessed with money, with power, with justice, with a member of the opposite sex. The old movie obsessive can identify with these characters; we know what it’s like to have a passion that is all-consuming, which takes over our lives.

But classic film buffs like me love Noir for another reason too: Film Noir satisfies our obsessions. Beneath the surface of these B-movie programmers with their tightly woven plots and genre thrills, old movie obsessives can find complex, multi-layered themes and characters; hidden, coded messages about society and the human psyche; and a wealth of stylistic touches that make these films an endless source of study and analysis for the dedicated cinephile. In less than 90 minutes, your average film noir can provide an old movie obsessive with hours, days, years of film geek fun.

That’s what we’ve got with SCANDAL SHEET, a well-written, gritty and cynical little crime flick from director Phil Karlson, starring Broderick Crawford, John Derek, and Donna Reed, and based on a novel by Samuel Fuller (yeah, that Sam Fuller). It aired on TCM May 19, 2010 (2:00 AM EST) as part of their Star of the Month tribute to Ms. Reed and it’s my Classic Cinema Obsession of the Week.

SCANDAL SHEET has a great hook: A star reporter for a New York tabloid investigates a murder that turns out to have been committed by the tabloid’s editor-in-chief. Crawford plays the editor of the New York Express, a man named Mark Chapman; John Derek is the ace reporter for the Express, Steve McCleary; and Donna Reed is a feature writer named Julie Allison, who hates the tabloid direction the New York Express has taken under Mark Chapman’s leadership. It’s a tense thriller and a cynical, biting expose of the tabloid journalism racket.

Like any decent films noir, SCANDAL SHEET is entertaining and tightly plotted with the requisite twists and turns. But like the better films noir, SCANDAL SHEET uses all the elements of cinema — lighting, mise en scene, sound, dialogue, repetition of visual motifs — to make a deeper point and explore a powerful theme. SCANDAL SHEET is about image, reality, identity, and exploitation; about how we see other people and how we objectify each other. It’s about how we see ourselves, how we try to construct an image of ourselves for the world to see. It’s a film about the reality and illusion of images; about the power of pictures and faces to reveal AND deceive. It’s a film about identity and class and the power of the media to exploit and yet, at the same time, to find truth.

SCANDAL SHEET is a film steeped in irony. Immediately after the first turning point (when Chapman murders a woman from his past) we watch as dramatic irony builds upon dramatic irony. The characters’ ambitions are eventually their downfall. No one seems to be who they pretend to be or who the world thinks they are.

It’s a film about faces.

It’s about how faces reveal and conceal. We watch a parade of faces — many of them the dregs of society, the losers and the lower classes — and we watch as the powerful and successful use and ridicule these poor souls.

Chapman calls them “slobs.” He looks down on all the “Lonely Hearts.”

McCleary the reporter calls them “suckers” even as he uses them for information.

Even Donna Reed’s Julie (the moral center of the film) calls the Express’s readers “poor, ignorant dopes.”

Phil Karlson is the master of interesting faces.

In his other feature of 1952, KANSAS CITY CONFIDENTIAL, Karlson cast three of the all-time greatest faces in classic cinema to play the heist men: Jack Elam, Lee Van Cleef, and Neville Brand.

Karlson doesn’t skimp on the faces in SCANDAL SHEET either. In the first scene he takes us from midtown Manhattan to the lower East side. He shows us the grime and degradation of the lower classes. He shows us a face.

The woman has witnessed a murder. A husband in her building took a meat axe to his wife’s face. The woman tells the reporter, McCleary, what she saw and Harry Morgan’s gadfly news photographer snaps the picture:

Morgan’s cameraman always seems to be around, a ubiquitous presence, reminding us of the importance of images and the photographed face.

Immediately in this opening scene we are confronted with the film’s two great motifs: The Human Face and the Photograph. These two motifs will eventually become not only visually important but also important to the plot, as later in the film, Mark Chapman waits for someone to recognize his face in a photograph and peg him for the murder of Rosemary De Camp’s “Miss Lonely Heart.”

After the opening scene on the lower East side, we watch as the next 80 minutes pile up frame after frame of photographs and faces. Like all good newspaper films, SCANDAL SHEET has its share of shots of newspaper headlines, but director Karlson practically bombards the audience with shot after shot of headlines and photos, with characters reading the tabloid and looking at the pictures.

Characters take pictures, look at pictures, flip through the newspaper and examine the pictures inside. Pictures provide evidence; pictures provide truth. Pictures are lurid and exploitative. Pictures remind characters of their pasts. And all of these pictures are of people, of their faces. We see photos of Miss Lonely Heart at the Lonely Hearts ball, then we see photos of her dead in her bathtub.

We see the face of former report Charlie Barnes (played by Henry O’Neill), now a drunk, a “rum dum” according to Chapman. He’s scruffy and unkempt, bleary-eyed and obviously down on his luck. But we are told he was once a great reporter, a Pulitzer Prize winner. We see his photo on the wall of a restaurant and we see the face of another man, a man who had it all, who was a success.

Characters are always looking at each other’s faces, always trying to tell who it is they are really seeing.

Success and failure are key themes in the film. Mark Chapman wants success. He wants fame and money. He wants to sell as many newspapers as possible. When the paper reaches 750,000 in circulation, Chapman receives a large bonus from the stockholders. A huge chart is on display in the news room, keeping track of the circulation numbers for the paper, looming over everything and everyone in the office.

Not by coincidence, the chart is displayed like a huge clock face, ticking off the numbers until 750,000. It is another FACE, a face that hangs over Chapman and his fate; an ironic reminder that as the headlines of Miss Lonely Heart’s murder grow bigger and sell more papers, the closer Chapman gets to his goal of the big bonus — and the closer Chapman gets to being found out for the murder.

Charlie Barnes wants success again too. He’s part of the lower classes now, but he still looks down on them, pushing away his fellow bums, trying to reach back up and get to the top of the journalism world again.

John Derek’s reporter, McCleary, wants fame and success too. He’s callous and cruel towards the dopes and suckers he reports on. He makes fun of murder victim Miss Lonely Heart’s dresses; he plasters her pathetic murdered face all over the paper in order to sell copies and get his name on the front page.

Faces. Photos. Image. Reality.

Characters are constantly observing or commenting on other people’s photos, on other people’s faces — on other people’s images and identities.

Who is Mark Chapman really? A big shot editor or a murderer?

Who is Charlie Barnes? A washed-up drunk or a Pulitzer Prize winning investigative reporter?

Who is Miss Lonely Heart? A pitiable woman, a loser, a dope? Or a person who deserves to be treated with respect and dignity simply because she is a human being?

The people in the tabloid business know the power of images. They know that images are everything. And director Karlson knows this power as well. He fills the screen with the faces of the “cheap and depraved,” with the “slobs” and the “dopes.” Karlson’s view is a cynical one: The people on the top, the elitists, the snobs, the successful people like Chapman and the stockholders, they don’t really see these forgotten misfits. They exploit them but they don’t really see them as people. They just flash their cameras and use these poor faces to sell newspapers.

And yet, these forgotten little people will be the ones to eventually “see” Chapman for what he really is. They will be the ones who will add pieces to the puzzle for the reporter, McCleary, to put together.

The face of Chapman — however respectable he may seem on the surface — is a face caught between light and shadow. From shadow to light and back to shadow again.

He’s a man who hides his true identity, who wears a face that disguises the dark, depraved soul inside.

SCANDAL SHEET is a little gem of a movie that’s anchored by a clever, literate script; stellar acting (especially by its supporting cast); and a visual style that enhances and deepens the film’s story and themes. Karlson is a director who knows the power of the human face and the power of the photographic image. The film’s cinematographer is Burnett Guffey of BONNIE AND CLYDE fame, as well as a host of other great films noir.

If you missed the airing on TCM, SCANDAL SHEET is available as part of the SAMUEL FULLER FILM COLLECTION on DVD.

SCANDAL SHEET is a cynical little noir that’s obsessed with the photographic image and with the human face — obsessed with image and identity, with the power of the photographic image to reveal truth even as it exploits it — and thanks to this photographic obsessiveness it’s the perfect choice for my Classic Cinema Obsession of the Week.

One thought on “Classic Cinema Obsession: SCANDAL SHEET (Phil Karlson, 1952)”

Comments are closed.