[Dr. Li-ling Hsiao, a longtime friend of Libertas, is Associate Professor and Assistant Chair of the Department of Asian Studies at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. This article appears in the 2010 issue of the Southeast Review of Asian Studies.]

By Dr. Li-ling Hsiao. On a dimly lit stage, an old man lifts a cane and lights the red lanterns. Accompanied by the spare sound of ringing bells, the lanterns gradually rise like an ascending curtain and reveal a stage space for the dance of red lanterns performed by a corps de ballet dressed in blue. A female voice, singing in the style of the Peking opera, gradually becomes audible. This prelude opens Dahong denglong gaogao gua or, as it is better known in the West, Raise the Red Lantern. The performance combines elements of ballet, modern dance, and Peking opera. The conflation of East and West governs every creative aspect of the ballet, which explains why it has been acclaimed equally in China and throughout the world.

The ballet is the brainchild of Zhang Yimou (b. 1951), who made his name in the West as the director of the renowned Chinese film Raise the Red Lantern (1991). Zhang won the best director award at the Venice International Film Festival in 1991, and the film received an Academy Award nomination as best foreign film in 1992. Subsequent films like Shanghai Triad (1995), Hero (2002), House of Flying Daggers (2004), and Curse of the Golden Flower (2005) sealed Zhang’s reputation as a giant of world cinema, while his direction of the extravagant opening ceremony of the 2008 Olympic Games in Beijing made him an international celebrity. Given his penchant for stunning visual pattern, Zhang’s interest in the highly stylized media of opera and ballet is hardly surprising. The ballet – his first – premiered in Beijing in 2001 and has since played in Europe and America. A revised version of the ballet, featuring the National Ballet of China, with music by Chen Qigang and choreography by Wang Xinpeng and Wang Yuanyuan, appeared on video in 2005, encouraging an assessment of what Zhang has both achieved and failed to achieve.

The ballet is the brainchild of Zhang Yimou (b. 1951), who made his name in the West as the director of the renowned Chinese film Raise the Red Lantern (1991). Zhang won the best director award at the Venice International Film Festival in 1991, and the film received an Academy Award nomination as best foreign film in 1992. Subsequent films like Shanghai Triad (1995), Hero (2002), House of Flying Daggers (2004), and Curse of the Golden Flower (2005) sealed Zhang’s reputation as a giant of world cinema, while his direction of the extravagant opening ceremony of the 2008 Olympic Games in Beijing made him an international celebrity. Given his penchant for stunning visual pattern, Zhang’s interest in the highly stylized media of opera and ballet is hardly surprising. The ballet – his first – premiered in Beijing in 2001 and has since played in Europe and America. A revised version of the ballet, featuring the National Ballet of China, with music by Chen Qigang and choreography by Wang Xinpeng and Wang Yuanyuan, appeared on video in 2005, encouraging an assessment of what Zhang has both achieved and failed to achieve.

The story of the Red Lantern originates in a novella titled Wife and Concubines by Su Tong (b. 1963) published in 1990. Su Tong’s novella tells the story of a nineteen-year-old college student, Songlian, who marries into a rich household and becomes the fourth concubine of the much older master. The novella centers on the vicious competition and relentless jealousy governing the household world of the wives, concubines and maids, and on the friendship that develops between Songlian and the elder son of the master, Feipu, which verges on transgression. As these two plot lines progress, Songlian increasingly withdraws into solitude and self-confinement, while the abandoned well in which several concubines have died looms threateningly outside her room. Her attempt to distance herself from the intrigues of the household, however, does not prevent her from striking back after being slandered, resulting in the death of her maid and the loss of her master’s favor. After witnessing the adulterous third wife’s death by drowning in the well, Songlian loses her mind and becomes an invalid inmate of the household.

Zhang Yimou’s film brings a stunning visual aestheticism to Su’s story, while engaging in a significant plot revision. In the novella, Songlian attempts to remain above the petty intrigues of the household, but in the film she quickly succumbs to something devious and dark in her own nature and becomes as fully Machiavellian as the other women. The film thus assumes a moral and dramatic weight missing from the novella: Zhang’s Songlian is no mere innocent victim of circumstance, but a complex moral agent whose downfall is largely her own doing. In both novella and film, Songlian is the unintentional victimizer of the maid, but in the film she is the effective murderer of the third wife, whose infidelity she reports to the treacherous second wife, knowing, in some recess of her mind, that her tale is the death warrant of a competitor. Significantly, the novella envisions Songlian crazed by circumstance, while the film envisions her crazed by guilt. Zhang thus reconceives the story as a parable of the self caught in the fate it has created, and the film becomes a Shakespearean tragedy played out in a Chinese social context. The ingénue of the novella is no more; she has been replaced by the tragic heroine.

Zhang also accentuates the story’s symbolic elements, bringing a new complexity and intensity to the story. Most significantly, the film elevates the lantern, which the novella mentions only peripherally as a crucial leitmotif. In Zhang’s film, the lantern hangs in the courtyard of the lady with whom the master intends to spend the night. Fantasizing about being a wife or concubine, the maid, Yaner, raises her own red lantern, which provides Songlian with an excuse to mete out harsh punishment and unleash her own frustrations. She forces Yaner to kneel in the courtyard until the maid dies in the snow. Thus, the red lantern, an auspicious symbol, becomes a symbol of illicit desire and ambition as well as a morally ambiguous marker of the master’s favor. Zhang also makes an important symbol of the small hammers used to massage the feet of the wives and concubines. The massage, like the lantern, is a symbol of privilege, and the clicking sound of the hammer echoes throughout both the household and film, indicating the constant competition for favor. The sound of the hammer likewise has erotic connotations, suggesting the physical ministrations enjoyed by some but denied to others. Zhang brilliantly utilizes the symbolic elements to underscore the silent drama that plays out within the household; the symbolism allows Zhang to explore the intricacies of his domestic drama without impinging on the silence and the isolation that is its subtext. Finally, Zhang shifts symbolic emphasis from the well (a crucial motif of the novella) to a small stone room on the roof of the compound. Both symbolize the tragic fate of unfaithful women, but the room, situated above, suggests a totalitarian world of observation and control, and represents the panoptic eye of the master and his minions. Zhang achieves this effect by frequently adopting a rooftop perspective on the action below, taking in the stone room in what seems an incidental fashion. Visually, Zhang implants the room as a subconscious consideration and thereby prepares for its powerful revelation as a place of execution when the third wife is carried there, as if in funeral procession, at the end of the film. Zhang thus makes clever use of his actual location, the Qiao Compound in Pingyang, Shanxi Province, and turns an accidental feature of the structure – perhaps a harmless storage shed or recreational pavilion – into a haunting symbol of power and the dread of power.

Zhang also accentuates the story’s symbolic elements, bringing a new complexity and intensity to the story. Most significantly, the film elevates the lantern, which the novella mentions only peripherally as a crucial leitmotif. In Zhang’s film, the lantern hangs in the courtyard of the lady with whom the master intends to spend the night. Fantasizing about being a wife or concubine, the maid, Yaner, raises her own red lantern, which provides Songlian with an excuse to mete out harsh punishment and unleash her own frustrations. She forces Yaner to kneel in the courtyard until the maid dies in the snow. Thus, the red lantern, an auspicious symbol, becomes a symbol of illicit desire and ambition as well as a morally ambiguous marker of the master’s favor. Zhang also makes an important symbol of the small hammers used to massage the feet of the wives and concubines. The massage, like the lantern, is a symbol of privilege, and the clicking sound of the hammer echoes throughout both the household and film, indicating the constant competition for favor. The sound of the hammer likewise has erotic connotations, suggesting the physical ministrations enjoyed by some but denied to others. Zhang brilliantly utilizes the symbolic elements to underscore the silent drama that plays out within the household; the symbolism allows Zhang to explore the intricacies of his domestic drama without impinging on the silence and the isolation that is its subtext. Finally, Zhang shifts symbolic emphasis from the well (a crucial motif of the novella) to a small stone room on the roof of the compound. Both symbolize the tragic fate of unfaithful women, but the room, situated above, suggests a totalitarian world of observation and control, and represents the panoptic eye of the master and his minions. Zhang achieves this effect by frequently adopting a rooftop perspective on the action below, taking in the stone room in what seems an incidental fashion. Visually, Zhang implants the room as a subconscious consideration and thereby prepares for its powerful revelation as a place of execution when the third wife is carried there, as if in funeral procession, at the end of the film. Zhang thus makes clever use of his actual location, the Qiao Compound in Pingyang, Shanxi Province, and turns an accidental feature of the structure – perhaps a harmless storage shed or recreational pavilion – into a haunting symbol of power and the dread of power.

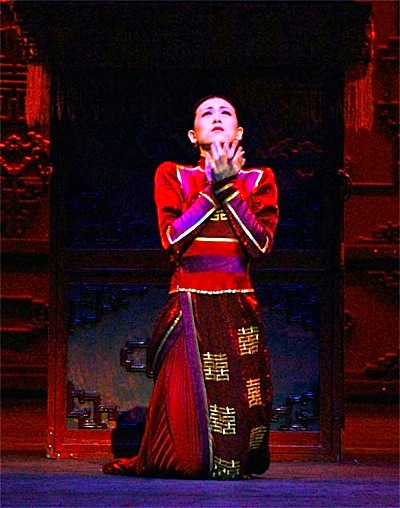

In its emphasis on color and pattern, the ballet attempts to replicate the film; however, the ballet struggles to capture the plot intricacies and the moral nuances of the film, and tells a simpler story of tragic love involving Songlian (played by the prima ballerina), Songlian’s lover (a plot addition), two older wives, and the master. Songlian and her lover (played in the style of the male protagonist or xiaosheng of Peking Opera) engage in a clandestine affair, which the second wife discovers and reports. The master orders the execution of the couple, as well as the second wife, the latter in apparent punishment for being the bearer of bad news. In its de-emphasis of the political struggles among the women of the household, the ballet is closer to the novella, which hints at a romance between Songlian and Feipu without suggesting actual infidelity. Like the film, the ballet adopts the lantern as its center, but removed from the context of the film’s symbolic system, the lantern becomes merely decorative. The lantern is lit at the beginning of the performance and again when Songlian steps from the bridal sedan chair while surrounded by the corps de ballet. The symbolic meaning of the lantern is not clearly introduced, and the viewer naturally assumes the red lantern means no more than it usually does when lit as part of the marriage ceremony. The second wife lights her own lanterns after losing the master’s favor (a deviation from the film, which assigns this audacity to the maid), but the scene seems to presuppose a symbolic meaning that has not been established, and the scene seems arbitrary and even confusing.

Zhang seems to realize that ballet is about the elaborate ornamentation of a simple plot line, but he appears to be caught up in his own visual extravaganza to the detriment of what should be his primary emphasis: the expressive potential of dance. There is an instructive contrast with Lin Hwai-min (b. 1947), director of Taiwan’s Cloudgate Dance Company. No less than Zhang, Lin is a master of visual spectacle, but his elaborate lighting and flowing silks accentuate, rather than distract from or compete with, the expressive effort of the dance itself. In general, Zhang remains too much the filmmaker. He seems unsure how to make dance serve his purposes. Lacking Lin’s intimate understanding of the body and the body’s unconscious symbol-language, he conceives the dance as a mere component in a multimedia spectacle, not realizing that the moving body is intrinsically privileged and inescapably central. Ironically, Gong Li’s performance as Songlian in the film is brilliantly bodily, while the ballet tends to be physically inert.

Zhang seems to realize that ballet is about the elaborate ornamentation of a simple plot line, but he appears to be caught up in his own visual extravaganza to the detriment of what should be his primary emphasis: the expressive potential of dance. There is an instructive contrast with Lin Hwai-min (b. 1947), director of Taiwan’s Cloudgate Dance Company. No less than Zhang, Lin is a master of visual spectacle, but his elaborate lighting and flowing silks accentuate, rather than distract from or compete with, the expressive effort of the dance itself. In general, Zhang remains too much the filmmaker. He seems unsure how to make dance serve his purposes. Lacking Lin’s intimate understanding of the body and the body’s unconscious symbol-language, he conceives the dance as a mere component in a multimedia spectacle, not realizing that the moving body is intrinsically privileged and inescapably central. Ironically, Gong Li’s performance as Songlian in the film is brilliantly bodily, while the ballet tends to be physically inert.

Raise the Red Lantern tells a thoroughly traditional Chinese tale, recalling, for example, the famous Ming novel Jin Ping Mei (The Plum and the Golden Vase, seventeenth century). Zhang’s archaic instinct for repetitive pattern and sumptuous color is well suited to this material, as the film demonstrates. The ballet preserves traditional Chinese elements in its costumes and set design, but the conventions of the ballet necessarily introduce a Western element that can be discordant. The score, for example, is an experimental fusion of Western and Chinese music. Some of the music derives directly from the Peking Opera, but much of the music combines Chinese melody and instrumentation with the dissonant effects of Western modernism. The most successful musical interlude occurs during the dance that narrates the jealous reaction to the arrival of the new bride and the introduction of the master. The females are accompanied by Chinese music heavy with percussion, while the master and his servants are accompanied by jagged shards of sound that recall Stravinsky’s Rites of Spring. Here, the music is not attempting to define the mood, but to function as the rhythm of the dance; moreover, the music underscores the distinction between male and female so essential to the basic idea of the story. Here the music and the dance work together to tell the story, while they otherwise tend to compete or simply to misunderstand one another. Once again, Zhang is too much the filmmaker, lacking an instinctive feel for the requirements of successful ballet; sensorily, he is all eye and not enough ear.

The props and the costumes are mostly Chinese. The qipao (the Chinese dress popularized in Shanghai during the 1930s) defines the natural line of the upright body rather nicely, but the qipao’s elegance derives from its form-hugging constriction, which works against the expressive movement of ballet and modern dance. Whether the dancers’ movements are actually hindered, the dress gives the impression that they are hindered and leaves the viewer cringing in expectation of split seams and bared bottoms – the balletic equivalent of Janet Jackson’s infamous ‘wardrobe malfunction.’ Moreover, the stiffness of the dresses cannot accommodate the shifting lines of the dancers’ bodies; the precise outlines are obscured, and the fabric tends to bunch rather than flow. In order to accommodate leg movement, the dresses have an unusually high slit, revealing a good deal of hip and buttock and contradicting the erotic logic of the qipao, which is to suggest the contours of the body while keeping it carefully concealed.

The props and the costumes are mostly Chinese. The qipao (the Chinese dress popularized in Shanghai during the 1930s) defines the natural line of the upright body rather nicely, but the qipao’s elegance derives from its form-hugging constriction, which works against the expressive movement of ballet and modern dance. Whether the dancers’ movements are actually hindered, the dress gives the impression that they are hindered and leaves the viewer cringing in expectation of split seams and bared bottoms – the balletic equivalent of Janet Jackson’s infamous ‘wardrobe malfunction.’ Moreover, the stiffness of the dresses cannot accommodate the shifting lines of the dancers’ bodies; the precise outlines are obscured, and the fabric tends to bunch rather than flow. In order to accommodate leg movement, the dresses have an unusually high slit, revealing a good deal of hip and buttock and contradicting the erotic logic of the qipao, which is to suggest the contours of the body while keeping it carefully concealed.

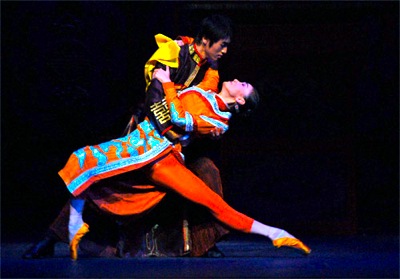

The choreography goes a step farther in the attempt to produce a hybridity of Chinese and Western dance. Its basic point of reference is the Western ballet, but it incorporates the shenduan, or stylized gestures, of the Peking Opera. The ambition is bold and admirable, but the result leaves something to be desired. Following the classical ballet, the choreography features a number of pas de deux involving the prima ballerina and the male lead. The first occurs in the first scene, in which Songlian journeys to her new home and meets her lover on the way. The male lead is costumed in full military armor. He wears high-healed shoes in the manner of the Peking opera, and six pennants rise from his backplate. According to the conventions of Peking opera, these pennants signify a soldier in the midst of battle. Burdened with all of this paraphernalia, the dancer can perform only the simple, stylized shenduan of the Peking opera even as he attempts to fulfill the usual partnering duties of the male ballet dancer (lifting, supporting, etc.). The pairing of the clunky male and the fluid female seems odd and uncoordinated, as if the dancers had accidentally wandered onto the same stage.

The second scene features a meta-performance that embeds a Peking opera performance within the ballet to celebrate the master’s birthday, which is central in the novella but marginalized in the film. An operatic performance is appropriate to such a celebration and does not seem gimmicky. In the second scene, the operatic performance forms the backdrop for the prima ballerina’s solo and the pas de deux of the ballerina and her lover. The two dances simultaneously narrate the same drama of forbidden love, creating an obviously meaningful juxtaposition and, perhaps, symbolizing the aesthetic aspiration of the ballet itself. The skill of the operatic performers, however, clearly contrasts with the laborious exertions and relatively poor coordination of the dancers. The operatic performers who fight with lances in the second scene are likewise models of impeccable stylization, at odds with the rest of the program. These painful contrasts underscore that the Western element remains a stubbornly foreign element and that Chinese ballet cannot, for the moment, compete with the ancient and culturally central traditions of Peking opera.

The second scene features a meta-performance that embeds a Peking opera performance within the ballet to celebrate the master’s birthday, which is central in the novella but marginalized in the film. An operatic performance is appropriate to such a celebration and does not seem gimmicky. In the second scene, the operatic performance forms the backdrop for the prima ballerina’s solo and the pas de deux of the ballerina and her lover. The two dances simultaneously narrate the same drama of forbidden love, creating an obviously meaningful juxtaposition and, perhaps, symbolizing the aesthetic aspiration of the ballet itself. The skill of the operatic performers, however, clearly contrasts with the laborious exertions and relatively poor coordination of the dancers. The operatic performers who fight with lances in the second scene are likewise models of impeccable stylization, at odds with the rest of the program. These painful contrasts underscore that the Western element remains a stubbornly foreign element and that Chinese ballet cannot, for the moment, compete with the ancient and culturally central traditions of Peking opera.

In the climax of the ballet, the two wives and the lover are caned to death. The domestics who perform the execution are, oddly enough, dressed as soldiers, their uniforms recalling those in the Zhang’s acclaimed film Hero. Zhang may want to associate their cruelty with the brutality of the Qin (third century B.C.) army and the murder of the three innocents with the political oppression perpetrated by the Qin dynasty, but this over-the-top anachronism seems radically at odds with the subtle suggestions of dance and furthermore overturns the secrecy and mystery surrounding the punishment meted out to the unfaithful wives. In this scene, the body’s power to imply pain and anguish through subtle inflection is completely overshadowed as the soldiers smash the canvas backcloth with seven-foot rods while the three dancers writhe in the foreground. The scene is frenzied, ungainly, and loud, and Zhang may believe that this is entirely to the point, but a more knowing student of the classical ballet would understand that the dance must suggest inelegance while itself remaining scrupulously elegant. This climax may have an internal logic in theory, but from the perspective of the disgruntled viewer it comes to seem a weirdly symbolic attack on dance as an expressive medium and a frustrated acknowledgment that the performance has failed.

The fusion of Eastern and Western is far from impossible, as demonstrated by the painting of Lin Fengmian (1900-91) and the dance of Lin Hwai-min, on the one hand, and by the art of James McNeill Whistler (1834-1903) and the poetry of Ezra Pound (1885-1972), on the other. Zhang himself successfully weds East and West in his films, most especially in Shanghai Triad, which begins as homage to the American gangster film but gives way to a mood of bitter lyricism that is entirely Chinese. In all cases, however, this marriage depends on a mastery of the medium, a control firm enough to accommodate the foreign element. Zhang is a supremely gifted film director who has trespassed on a discipline that is not his own; like Songlian, he attempts to maneuver in a world he only partially understands, with similarly unfortunate results.

The fusion of Eastern and Western is far from impossible, as demonstrated by the painting of Lin Fengmian (1900-91) and the dance of Lin Hwai-min, on the one hand, and by the art of James McNeill Whistler (1834-1903) and the poetry of Ezra Pound (1885-1972), on the other. Zhang himself successfully weds East and West in his films, most especially in Shanghai Triad, which begins as homage to the American gangster film but gives way to a mood of bitter lyricism that is entirely Chinese. In all cases, however, this marriage depends on a mastery of the medium, a control firm enough to accommodate the foreign element. Zhang is a supremely gifted film director who has trespassed on a discipline that is not his own; like Songlian, he attempts to maneuver in a world he only partially understands, with similarly unfortunate results.

Posted on October 10th, 2010 at 8:11pm.

he fusion of Eastern and Western is far from impossible . .

Japanese prints = Alfons Mucha posters

Not to mention the ballets where the girls were dancing with Red Army uniforms and rifles while chasing imperialists.

It would be great to stage a comedic ballet/opera based on same.

ADD: Thanks for the article. I just bought the DVD of the ballet based on your piece here.

Sounds like a wonderful film to see. What an interesting cultural combination – the Peking Opera and Western ballet. Has Dr. Li-ling Hsiao ever written a review of “Dream of the Red Chamber”? Don’t know if it has ever been filmed but it is a current full-length dance drama that is currently doing the rounds of theatres in North America and sounds similar in that it has been termed “A seamless fusion of ballet, modern dance and traditional Chinese dance” by the “Toronto Star.” It is performed by the Bejing Friendship Dance Company.