[Editor’s Note: the post below appears today on the front page of The Huffington Post.]

By Govindini Murty. Few directors are as willing to venture into the abyss as Werner Herzog. His prolific body of work has ranged from intense dramas like Aguirre: The Wrath of God and Woyzeck that plumb the depths of the human soul to documentaries like Encounters at the End of the World and Grizzly Man that examine humanity’s fragile place in the miraculous and terrifying world of nature. The astonishing breadth of Herzog’s filmmaking conveys the humanist’s sense of wonder at the world – what he describes as the “ecstasy of observation.”

Herzog’s latest film, Into the Abyss: A Tale of Death, A Tale of Life (opening this Friday, November 11th) is a compelling look at the contentious issue of the death penalty. Producer Erik Nelson has stated that the film is intended to inform the current Republican presidential debate over the death penalty, in particular with regard to the candidacy of Texas Governor Rick Perry. Herzog himself has issued a Director’s Statement expressing his opposition to capital punishment – though in keeping with his lifelong aversion to political interpretations of his work, he has also asserted that Into the Abyss is not a political film. These apparent contradictions point to the enigma of Werner Herzog himself – on the one hand a sensitive humanist with strong moral convictions, yet on the other hand an artist who resists being defined by political activism or party ideology.

Into the Abyss embodies these contradictions. The film tells the true story of a brutal triple murder committed in Conroe, Texas. Michael Perry and Jason Burkett, intending to steal two cars owned by Sandra Stotler, killed Stotler in her home and then lured her son Adam and his friend Jeremy Richardson into the woods and executed them. Perry and Burkett subsequently went on a joy ride in the cars, before winding up in a bloody shoot-out with the police. Perry and Burkett were convicted of the murders, with Perry receiving the death penalty, and Burkett receiving a life sentence.

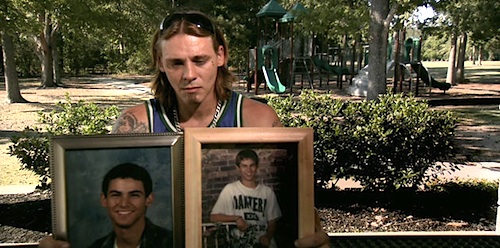

Herzog interviewed Michael Perry just eight days before his execution, and also interviewed Jason Burkett in prison. Other interviews include those with Burkett’s wife Melyssa Thompson-Burkett, who contacted Burkett while he was in prison and subsequently married him; Fred Allen, a prison captain who worked in the execution chamber and who assisted in over 125 executions before resigning in moral crisis; and most significantly, the relatives of the victims themselves: Lisa Stotler-Balloun, the daughter of Sandra Stotler and sister of Adam Stotler, and Charles Richardson, the brother of Jeremy Richardson. Stotler-Balloun and Richardson in particular provide the most heartbreaking testimony of the film, as Herzog does not shy away from depicting the shattering effect of the murders on their lives. As a result, Into the Abyss exists in a complex tension between Herzog’s avowed position against capital punishment and his impulse as a storyteller to depict both sides of the story and allow readers to make up their own minds.

I had the opportunity to meet with Werner Herzog in Los Angeles recently and discuss with him Into the Abyss and his extraordinary body of work. Part I of this interview appears below.

GM: I’d like to ask you about the title of your movie, Into the Abyss, because I’ve seen you refer to the concept of ‘the abyss’ quite a few times in your work. In Woyzeck you have a line “Every man is an abyss, you get dizzy looking in,” and in Nosferatu you have a line “Time is an abyss profound as a thousand nights.” This is a concept you keep referring to – what does ‘the abyss’ mean to you?

WH: It’s a good observation, and when I came up with the title Into the Abyss – it dawned on me that it could have been the title of quite a few other films. Like Woyzeck could have had that title, or The Great Ecstasy of Woodcarver Steiner or even the cave film, Cave of Forgotten Dreams, because I’ve always tried to look deep inside of what we are – deep into the recesses of our existence, of our prehistory – like in Cave of Forgotten Dreams. So it is some sort of a theme that runs through quite a few of my films.

GM: I want to ask you about the relationship between humanity and the universe. There was a wonderful quote at the end of Encounters at the End of the World where Dr. Gorham asks, and I paraphrase, “are we the means through which the universe becomes conscious of itself?” This reminded me of a quote from Blaise Pascal’s Pensées:

“A reed only is man, the frailest in the world, but a reed that thinks. Unnecessary that the universe arm itself to destroy him: a breath of air, a drop of water are enough to kill him. Yet, if the All should crush him, man would still be nobler than that which destroys him: for he knows that he dies, and he knows that the universe is stronger than he; but the universe knows nothing of it.” (Trans. A.J. Krailsheimer)

This seems to apply to Into the Abyss and its depiction of human beings within this world. In the film you go driving down country roads and you show the trailer parks, the run-down stores, the boarded up gas stations, the bars. It looks like a wasteland that God is somehow absent from, and there are these people in the midst of it who are in a terrible state of pain and confusion – in an apparently indifferent universe.

WH: Let me address Pascal first. Yes, I like him very much. I even invented a quote for the film Lessons of Darkness. It starts with a Pascal quote “The collapse of the universe will occur like the creation in grandiose splendor,” and underneath it says Blaise Pascal, but I invented it – and of course Pascal couldn’t have said it better. [Laughs.]

But, it’s interesting. The wasteland, this forlorn landscape, has become fascinating for me – this lost kind of Americana. And one of the death row inmates with whom I spoke – not in this film but in another film I’m already finishing – he said to me how he saw on his very last trip forty-three miles between death row and the death house where they are being executed in Huntsville. And in this cage in the van he sees a little bit of an abandoned gas station, he sees a cow in the field, and all of a sudden for him, everything is magnificent, and he says: “It looked like Israel to me, it all looked like the Holy Land.” And I immediately grabbed my camera and I did this voyage of the forty-three miles and indeed the most forlorn landscapes all of a sudden look like the Holy Land. So I look at these forlorn landscapes all of a sudden with fresh and different eyes.

GM: I was also very struck by the similarities in the comments of three of the people whom you interviewed. Lisa Stotler-Balloun spoke about the four years of terrible loneliness she suffered after the murders of her mother and brother, when her life was empty, when she lived withdrawn from the world and felt her life had no meaning. Then there was Michael Perry himself who, despite the fact that he had killed three people and was on death row, said that the circumstances he was in had no impact on him. He had literally blocked the prison walls out. And then there is Fred Allen, the former prison captain who worked in the execution chamber, who talked about quitting his job and finally discovering his real self. These are all different formulations of the same feeling of dissociation from the world through tragic circumstances – of being split from the world, cut off from reality, cut off from one’s own true self. This seems to be a recurring theme in modern filmmaking and literature.

WH: Yes, but … we shouldn’t speak about Perry who was executed eight days later. It was some sort of a mechanism to keep his sanity – to talk himself into being innocent, although he had confessed twice, and in detail, and there is overwhelming evidence against him. So there’s no real doubt about his guilt. But the film is not in the business of guilt or innocence.

But let’s talk about Lisa Stotler-Balloun and Fred Allen, the former captain of the tie-down team. Both of them in a way are not disassociated anymore from the world, from friends and society. They have somehow managed to move back into it. Lisa Stotler has somehow overcome the worst of her nightmares. Fred Allen is a tormented soul, but somehow he’s back. He gave up his profession at the cost of losing his pension and today he has a company that does logistics – supplies for the trucking business. And he all of a sudden discovered for himself a very meaningful life where he sits back and watches nature and enjoys the birds. The film actually ends with the wonderful, wonderful text where he says he keeps watching the birds, and what are the ducks doing, and all the hummingbirds – pause – why are there so many of them? Cut. End of the film. What a fantastic question.

GM: It’s a very poetic ending. It reminds me of that shot of Klaus Kinski playing with the butterfly at the end of My Best Fiend, in terms of the individual having that connection with nature and life. So there’s hope after all for reintegration with the world.

Melyssa Thompson-Burkett was to me the final figure who was very striking – that she was drawn to this convicted killer. What is it in women that is drawn to that darkness in the death row inmates?

WH: You should answer it [chuckles], you are a woman.

GM: An urge to danger, an urge to nihilism, a desire to tame evil?

WH: I do not know. It’s very mysterious. There’s always a mystery between men and women, and thank God it exists. [Chuckles.] What kind of life would it be without this mysterious attraction that men and women have for each other, and love? It comes out of the blue, it comes out of nowhere. Melyssa meets the inmate for the first time and falls in love and she witnesses a rainbow from the gates of the prison – to her, she knows he’s innocent. And they belong together. So, in a way it’s very moving, but more mysterious than anything else.

GM: It’s in that mysterious space that all the good art and all the good filmmaking happens, where you have a chance to go into the world of the imagination, to go beyond the world of the intellect.

WH: Yes. That’s always been a quest of mine.

In Part II of this interview, I discuss with Werner Herzog his Rogue Film School (currently accepting applications), as well as his attitudes toward Avatar, pantheism, yoga, New Age nutritional supplements, Wrestlemania, and the end of civilization.

Posted November 11th, 2011 at 9:18am.

I grew up reading about the work of Werner Herzog and only recently been able to actually watch his films.(Thanks to Netflix, etc) A truly prolific and interesting person that never fails to fascinate. I enjoyed your article and look forward to the follow up.

johngaltjkt – thanks so much for your comment. Yes, Herzog is amazingly prolific (57 films to date!) and there is so much to enjoy in his films. In addition to Herzog’s work with Klaus Kinski in the ’70s and ’80s, I’m also a tremendous fan of his documentaries. “Encounters at the End of the World” in particular is a favorite. I really want to see “Cave of Forgotten Dreams,” as well. I wasn’t able to catch its brief engagement here in LA this spring, so I’m eagerly waiting for the DVD release on Nov. 29th.

Wonderful interview, Ms. Murty. I look forward to part II.

Your observation of the butterfly in ‘My Best Fiend’ reminded me of another “butterfly moment” of Herzog’s in ‘Aguirre’ – a little throwaway moment of on the conquistadors on board the raft on whose finger a butterfly has landed. He just gazes at it to the accompaniment of the flute player until it flies away, then the narrative resumes.

Thank you Lee – that’s a wonderful point about the moment with the butterfly on the raft in “Aguirre.” That’s what makes Herzog such a great filmmaker – his ability to notice and capture such details. I noticed the same thing when I met with him – how intelligent and observant he was of the people and environment around him.

Great post, Govindini. I was just thinking about how I wanted to see this film…

Another anti-death penalty film that has always interested me is Dead Man Walking. The text is that capital punishment is morally wrong because the killer is indeed a man with a (revived and redeemed) soul, yet the subtext is that this spiritual awakening was brought about by his death sentence. But for that, would he have ever acknowledged or experienced the sacred nature of life and his place in the human community?

Anyway, looking forward to Herzog’s take on it all. Will tune in for part 2.

That’s a really excellent point that you make Pat:

“the subtext is that this spiritual awakening was brought about by his death sentence. But for that, would he have ever acknowledged or experienced the sacred nature of life and his place in the human community?”

I think that’s the whole problem – people who kill do not appreciate the sacredness of life in the first place. The wasteland is internal with them – but they don’t realize that and go to their execution unenlightened (I use the Buddhist term deliberately here). Some do realize the sacredness of life when they have the finality of their own mortality thrust upon them – and then they realize that the world was holy the whole time and they should have treated it as such. It’s tragic that it has to come to that.

The question is, how do your inculcate a greater respect for life in human beings? Most people already have a natural sense of morality and respect for life – they don’t have to be taught it. But then there are those few who are completely lacking in that sense – what does one do with such people? Can society save them? Can religion or philosophy save them? And what about their victims and the wreckage they leave behind? Should the focus be less on saving them than limiting the terrible damage that they do?

We used to have carefully worked out religious guidelines on such issues, but having abandoned those, we are a society in free fall when it comes to dealing with the very real nature of evil in the world.

“We used to have carefully worked out religious guidelines on such issues, but having abandoned those, we are a society in free fall when it comes to dealing with the very real nature of evil in the world.”

Exactly. And in large part the guidelines were based on a sense of personal responsibility to hew to the moral law and penalties for those who do not. In an era of moral relativism and psychoanalytic analysis, that sense of personal responsibility is gone. Thus we are left with our confused thinking. Would the killer in DMW have been better off if he had gotten off on a technicality and continued his degraded life? I don’t know. We all die eventually anyway…

So what is the argument he’s making against the death penalty? That in the end the killers are enlightened, remorseful? I’m not getting it.

Actually, Herzog is making the point in the film is that all life, no matter how evil or degraded, is still inviolable and cannot be taken away by the state. He also issued a Director’s Statement in the press materials that explains further how his position grew out of his experiences suffering through Nazi Germany. Here’s Herzog’s statement from the “Into the Abyss” press materials:

DIRECTOR’S STATEMENT

“I am not an advocate of the death penalty. I do not even have an argument; I only have a story, the history of the barbarism of Nazi Germany.

There were thousands and thousands of cases of capital punishment; there was a systematic program of euthanasia, and on top of it the industrialized extermination of six million Jews in a genocide that has no precedence in human history.

The argument that innocent men and women have been executed is, in my opinion, only a secondary one. A State should not be allowed – under any circumstance – to execute anyone for any reason. End of story.”

– Werner Herzog

Thanks, Govindini.

Boy, do I hate that argument, and I speak as a Jew almost all of whose relatives from my father’s side were killed by the Germans. I see not the slightest comparison between the execution of such vicious, unthinking killers as those portrayed in the film and to the barbarities of the Germans under Hitler. To the contrary, the killers in this case are Nazis of a sort, writ small. I wonder: Does Herzog approve of the hanging of German leaders at Nuremberg? Were their lives too inviolable? One of the great gifts of human intellect is the ability to make fine distinctions. Herzog abuses that by lumping together all killing into one category. The response to German atrocity should not be to show mercy to those who commit their own atrocities.

Kishke –

I agree with you that Herzog’s argument is muddled, but he does at least concede that it’s based on something not really rational. At the same time, though, I would just note that when you read some of Herzog’s interviews for this film, he shows a nuanced understanding of what leads people (such as myself) to support the death penalty. The director’s statement is a little curt, and the fact that it might lead some to believe that he associates pro-death penalty people with Nazis is unfortunate, but Herzog has shown no tendency to demonize those who disagree with him when he gets a chance to explain himself.

There are real problems with getting true coherence out of Herzog’s worldview, and it leads him into some pretty dark places (cf. Aguirre, obviously; but also, say, Fitzcarraldo, where you get this idea of futile Sisyphean labor as a justification of human life). Then again, he’s not a philosopher, and ultimately his job is just to present his view of life as a whole as he sees it. For every film like “Into the Abyss” that might upset some conservatives, there is an “Even Dwarfs Started Small,” which is a full-on mockery of the puerile revolutionary antics of the Left.

Nonetheless, I clearly think you have a point. I would just encourage you not to give up on Herzog. He truly has a generous mind and spirit – he is not a hater, and not a flaming lefty by any means – and his vision is infinitely superior to that of most filmmakers working today, or indeed over the past forty years.

SeeSaw: Thanks for your thoughtful response. After reading that statement, I had pretty much decided in my mind to avoid Herzog’s work, but I’m glad to reconsider.

Great interview with one of my all-time favorite directors.

While I am, in the end, pro-death penalty, I have read other interviews with Herzog on this film and, as usual, his view is well considered, non-hysterical, and responsible. I completely respect it, and I especially respect that – as usual – he doesn’t tell people like me to go eff ourselves. One of Herzog’s best qualities is that even when he comes out of the political closet a little bit, he refuses to be baited into being claimed for a particular ideology. Every time I see him get interviewed someone tries to lure him into a larger condemnation of something, usually capitalism or America – think Stroszek and, lately, Bad Lieutenant. They’re doing the same with this film, and Herzog just will not play the game. I love his absolutely pig-headed independence, and the way in which he manages at the same time to not turn into a bitter, shrill a**-wad in expressing himself.

Interestingly enough, these qualities makes those who disagree with him more, not less, likely to listen to what he has to say. Would that other filmmakers could take the same approach. One of the things that makes Grizzly Man such an amazing achievement is the way he takes a man who someone like me would normally disdain and make fun of, and humanizes him – a lost soul, there but for the grace of God go I…

Anyway, I actually saw Cave of Forgotten Dreams on Movies on Demand, and it is a very quiet, meditative film – more like Fata Morgana and the last twenty minutes of Lessons of Darkness than Encounters at the End of the World or Little Dieter Learns to Fly. I found it somewhat rough going (as I did Fata Morgana), but nonetheless – an admirable film. Not one of my favorites, though.

SeeSaw – great points, as always. I really agree that Herzog’s more subtle approach, where he doesn’t beat people over the head with a political point and where he also is fair in showing both sides of a story, is far more likely to win people over to his side. He’s a smart man and he wants to be effective with his filmmaking, not just a controversialist, and this is why he’s avoided being baited into overtly political discussions. For example, I’ve seen a number of interviews where they’ve tried to get him to bash Texas or Rick Perry, and he absolutely refuses to, even going so far as to say he loves Texas. (Check out the interview he did on Collider for further details on this – I’ll post the link when I get a chance).

I’m very excited about seeing “Cave of Forgotten Dreams” – thanks for pointing out that it’s On Demand. I missed it in theaters and the DVD wasn’t coming out until the end of the month – nor was it on Netfliz of Amazon – so I was getting frustrated at not seeing it.

By the way, other Herzog documentaries I’ve really enjoyed include “The White Diamond” (absolutely charming, especially the portraits of the local Guyanese gentlemen!) and “The Wheel of Time” (beautiful account of a Tibetan Buddhist ceremony, with stunning shots of the Himalayas and the devout Tibetans who travel thousands of miles through them for the ceremony).

I LOVED the White Diamond, and I haven’t had a chance to see The Wheel of Time. Will do so soon.

You know I cry every time I see that scene in Lessons of Darkness when Herzog narrates some apocalyptic Biblical-style quote, the oil volcanoes blast out of the ground, and Arvo Part’s “Stabat Mater” haunts the scenery with its lamenting strings? Herzog’s ability to capture moments like that, those “sublime” moments when words just will not do the trick, is awe-inspiring. It doesn’t always work, but that is just the price for trying to do something so ambitious in the first place.