[Editor’s Note: the post below appears today on the front page of The Huffington Post and AOL-Moviefone.]

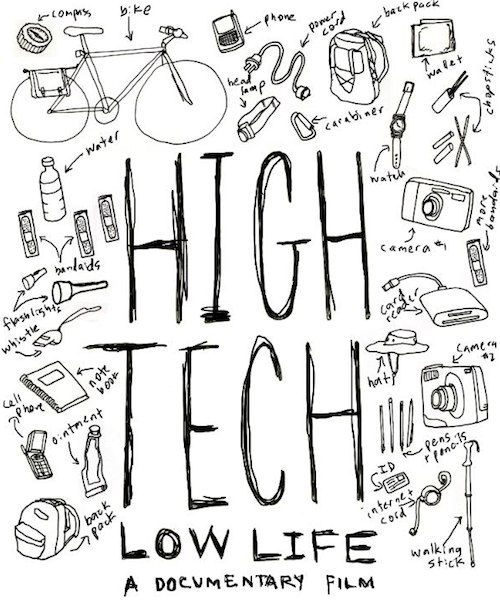

By Govindini Murty. Even as Chinese dissidents like Nobel laureate Liu Xiaobo and artist Ai Weiwei suffer physical imprisonment, hundreds of millions of their fellow Chinese citizens are suffering a form of mental imprisonment thanks to their nation’s system of internet censorship. For example, the Chinese government recently blocked on-line searches for words relating to the 23rd anniversary of the June 4th, 1989 Tiananmen Square massacre, censoring the terms “Tiananmen square,” “June 4th,” the number twenty-three, the words “never forget,” and even images of candles. The award-winning documentary High Tech, Low Life, currently screening at film festivals in the U.S., UK, and Australia, profiles two dissident Chinese bloggers who are working to challenge this Orwellian system.

Directed by Stephen Maing, High Tech, Low Life was in part funded by a Kickstarter campaign publicized on The Huffington Post and was an official selection of the 2012 Tribeca Film Festival. High Tech, Low Life documents the work of 57-year old blogger Zhang Shihe (known as “Tiger Temple”) and 27-year old Zhou Shuguang (known as “Zola”), two of China’s best-known “citizen reporters.” Even as the Chinese government uses internet technology to stifle dissent, these brave bloggers find creative ways to circumvent “The Great Firewall of China” and publish the truth about human rights abuses to the world. Along the way, Tiger and Zola suffer official harassment, familial disapproval, eviction, and arrest.

Blogger Zola describes in the film the vast apparatus of internet censorship that exists in China:

“There are 440 million netizens in China, 40,000 internal police monitor them, and 500,000 websites are blocked in China.” [Despite this,] “if an incident happens anywhere, netizens and citizen journalists will flock to the scene from all over the country. The censors might stop some of us, but they can’t stop all of us.”

Tiger Temple expands on the morally corrosive effect of the government’s censorship: “We’ve all been brainwashed. We’ve been listening to lies for too many years.” Although material prosperity may have improved in China, Tiger argues that life today is as bad as it was under Mao’s dictatorship. As Tiger puts it, the Chinese people are “complacent because they feel powerless.”

Tiger Temple and Zola could not be more different in style. The older, more experienced Tiger is a writer and former publisher living in Beijing who becomes closely involved in his subjects’ lives, bringing them food, money, and legal help. Tiger’s father was a high official in the Communist Party, but the family was persecuted by Mao during the Cultural Revolution in the ’60s. Tiger recalls how he and his family were beaten, evicted from their home, and exiled to the countryside. It was then, as a 13-year old, that Tiger says he started “roaming the country.”

Tiger Temple and Zola could not be more different in style. The older, more experienced Tiger is a writer and former publisher living in Beijing who becomes closely involved in his subjects’ lives, bringing them food, money, and legal help. Tiger’s father was a high official in the Communist Party, but the family was persecuted by Mao during the Cultural Revolution in the ’60s. Tiger recalls how he and his family were beaten, evicted from their home, and exiled to the countryside. It was then, as a 13-year old, that Tiger says he started “roaming the country.”

Tiger’s entry into blogging was almost accidental. Returning home one day from viewing an exhibition of Monet paintings in Beijing, he saw a woman being stabbed to death on the street by a man as bystanders watched. Horrified but unable to prevent the murder, Tiger grabbed his camera and documented its aftermath instead. He notes that when the police showed up, they were angrier at him for taking the photos than at the murderer himself, because such scenes would normally be censored from the press. Tiger went on to publish the photos online and caused a sensation, becoming known as China’s first “citizen journalist.” Tiger adds that he calls himself a “citizen” and not a “citizen journalist” because that way the government can’t ban him.

Years later, Tiger makes lengthy journeys on bike through the countryside to report on the lives of the rural poor who have suffered in the rush to urbanization. He is even on occasion tailed by agents of the government. In one trip documented in the film, Tiger bicycles 4000 miles to Er Loa, a village devastated by the illegal flooding of toxic waste by the local government. The floods of waste have caused the farmers’ homes to collapse and have made farming impossible. Villagers tell Tiger that local officials have warned them that if they complain too much they will be arrested. Not only does Tiger take photos and video of the environmental devastation, he also brings the villagers flour and noodles to feed them and tells them he has forwarded their information to a university in Beijing where law students are working to file a legal complaint with the authorities. Tiger interests an NGO in their case, and the farmers are ultimately brought to Beijing to speak at the Civil Society Watch’s Environmental Protection Conference.

As for the younger Zola, his rise from rural vegetable vendor to famous blogger is even more striking. As he puts it: “I used to be a nobody. Until I discovered the internet.” Zola’s first significant story comes about when he hears of the alleged rape and murder of a young girl at the hands of the son of a local government official in the county of Weng’an. The Chinese media isn’t covering it, so Zola goes to the village himself to see what is happening. He finds no reporters there – but plenty of police to keep an eye on the angry and grieving villagers. Zola attends the news conference where the local officials give an improbable reason for the girl’s death: they claim that she decided to jump off a bridge and commit suicide after watching a friend do three push-ups on the bridge. Zola goes to the bridge, does three push-ups, and sarcastically looks around to see if anyone feels an impulse to suicide. Zola’s reporting on the scandal causes the number of readers on his site to jump from about 200 a day to 200,000.

Zola typifies the new generation of young, brash Chinese bloggers. He is criticized at times by his readers for being too flamboyant and westernized, but by Western standards his youthful hijinks seem pretty tame. Zola declares “I just record what I witness,” unlike Tiger who gets actively involved in his subject’s lives. However, Zola’s bravery as a blogger goes well beyond mere observation. He repeatedly risks arrest by reporting on politically-sensitive subjects. In one scene, Zola interviews a man in Beijing whose house is about to be bulldozed to “beautify” a street in advance of the 2008 Beijing Olympics. As the man cries to Zola over the loss of his home, the bulldozers and the local police are poised just a few feet away. In another striking scene, Zola shows a small house sitting on a lonely island of earth in the midst of an enormous construction crater. The family inside has refused to vacate their home and the government is about to go in by force.

Zola’s parents don’t understand any of this. They disapprove of his career, considering his pro-democracy efforts destabilizing to the “large family” of China. They want him to settle down and do something that they consider more useful to the state, like farming and getting married.

In the course of their blogging, Tiger Temple and Zola suffer official harassment and intimidation. Tiger is arrested in the middle of the night and driven by ten police to the city of Xi’an to keep him out of Beijing during a Communist Party conference. Later, the police put pressure on his landlord and Tiger is evicted from his apartment. Disheartened, Tiger puts his modest belongings in storage and decides he will live on the road, riding his bike around China to document local abuses. As for Zola, he is threatened by intruders who assault his home in the middle of the night and is warned that the state security services intend to arrest him. When Zola is invited to speak at a blogger conference in Germany, his ticket is confiscated at the airport and he is prevented from leaving China. He finds out that the Public Security Agency has blacklisted him “as a threat to national security.” And although they’ve both found ways to host their blogs on foreign servers, both Tiger and Zola are still continually under threat of having their websites shut down or posts erased by the government.

When Tiger Temple and Zola eventually meet, there is a fascinating moment where Zola states: “I think the most important thing is to be conscious of the boundary between you and them.” This is the nub of the issue: how to keep one’s mental integrity even in the midst of corruption.

And when Zola worries that he’s too irreverent, Tiger responds “There are many kinds of warriors … you’re a playful warrior.” Zola is touched by this, and the interaction between the two men reminds me of that between Toshiro Mifune’s feisty farmer-warrior and Takashi Shimura’s older, experienced samurai in Akira Kurosawa’s The Seven Samurai.

Through an accumulation of closely-observed detail, High Tech, Low Life creates a devastating portrait of life in an authoritarian society. What makes the documentary all the more moving is how it reveals that no matter how powerful the Chinese government may seem to be, there are always Chinese citizens willing to risk their lives to speak out for freedom.

Tiger Temple and Zola’s solitary courage manifests true humanism: the idea that one feels a sense of obligation toward one’s fellow citizens without needing a coercive authority to make one act humanely. Indeed, these bloggers act justly despite the threats and intimidation of the Chinese state.

That the Chinese government, for all its apparent power, still feels threatened by such activists is made clear by the strenuous efforts it makes to deny their impact. There are some particularly telling TV clips in which news anchors on Chinese state TV ridicule democracy activists, claiming that “this kind of agitation is an act of vanity” that undermines “peace and social stability.” The anchors add: “Anyone looking for parallels to the Arab Spring will be sorely disappointed.” However, the Chinese are so frightened by the role that social media and the internet played in the Arab Spring that they create a new State Internet Information agency “to prevent disruptions to social stability.”

Tiger Temple questions the Chinese government’s concern for “social stability,” since this stability apparently involves the wholesale abridgment of its’ citizens human rights. As Tiger comments, it’s “as if bureaucratic order is more important than the law itself.”

LFM GRADE: A

Posted on June 8th, 2012 at 8:11am.