[Editor’s Note: The post below appears today on the front page of The Huffington Post and AOL-Moviefone.]

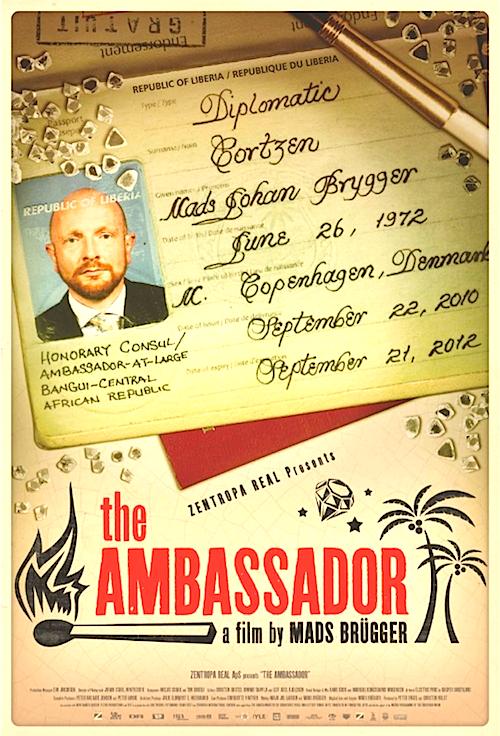

By Jason Apuzzo & Govindini Murty. His documentaries have been among the most provocative films featured in the Sundance Film Festival over the past several years. Bolder even than Sacha Baron Cohen, he’s punk’d both the North Korean communist government and now, in his new film The Ambassador, the Central African Republic and the corrupt diplomatic culture that supports it.

He’s one of Europe’s funniest and most controversial filmmakers, although most Americans haven’t heard of him — yet.

The name of this lanky, cerebral enfant terrible is Mads Brügger.

In Brügger’s previous film The Red Chapel (read the Libertas Film Magazine review of the film here), winner of Sundance’s 2010 World Cinema jury prize for documentaries, the filmmaker pulled off one of the most dangerous and politically provocative stunts in cinema history by infiltrating North Korea as part of a fake socialist comedy group. Operating under the watchful (and vaguely confused) gaze of the North Korean government, Brügger’s cameras proceeded to document the bizarre, Orwellian nether-world of today’s Pyongyang and its frightening cult of the ‘Dear Leader.’

In his new film The Ambassador (read the Libertas Film Magazine review of the film here), which recently screened at Sundance, Brügger now attempts an even more complex and daring stunt by purchasing a Liberian diplomatic title and infiltrating one of the most dangerous places on Earth — the Central African Republic (CAR) — as an ersatz Ambassador. His purpose? To expose the illegal blood diamond trade — and the corrupt world of CAR officials, bogus businessmen and shady European and Asian diplomats that it benefits.

Like a tragicomic version of Conrad’s Heart of Darkness, The Ambassador takes viewers into a rarely-seen world of European influence-peddlers who exploit the African continent — and the amoral retinue of African officials, petty businessmen and hangers-on who are complicit in the exploitation.

Along the way Brügger and his hidden cameras have close encounters with everything from an obese ex-French Legionnaire heading the CAR’s state security (who is assassinated shortly after talking to Brügger), to armed militias in the middle of Africa’s ‘Triangle of Death,’ to a diamond smuggler with a secret child bride and potential terrorist ties, to a tribe of inebriated pygmies organized by Brügger to staff a match factory.

It all makes for a potent, carnivalesque and politically incorrect experience — and one that exposes the mutual racism (of Europeans toward Africans, and Africans toward Europeans) that makes central Africa such a hotbed of corruption and violence.

In the midst of all this is Brügger himself — a tall, soft-spoken Danish journalist (and son of two Danish newspaper editors) with an ironic sense of humor and an uncanny ability to transform himself into the kind of diffident European grandee that African officials are accustomed to exploiting — and being exploited by — well into the 21st century.

Along with my Libertas Film Magazine co-editor Govindini Murty, I sat down with Brügger at the Sundance Film Festival to talk about his funny, horrifying and highly controversial new film. With a shaved head, and wearing a skull ring from DC Comics’ The Phantom, Brügger arrived looking very much the part of an experimental European director.

Apuzzo: What got you interested in [corruption in the Central African Republic] as subject matter for a film?

Brügger: I like doing films that divert from their own genre. I wanted to do an Africa documentary without all the usual semiotics and codes of the generic Africa documentary. You know — NGO people, child soldiers, HIV patients, and so on. But also I wanted a film where you would meet all the people you usually don’t get to see – you know, the kingpins, the players, the ministers who live a very secure and comfortable life away from the scrutiny of the media. So I thought that if I could purchase a diplomatic title, I could gain access to this very closed realm of African state affairs and politics. It’s pretty much a ‘let’s-see-what-happens’ project. Once we set off to do this, who will we meet? What kind of people will I run into?

Apuzzo: How did you prepare to become a corrupt European diplomat?

Brügger: [Laughs.] I prepared for almost three years, because I wanted to really go into detail with my persona. I would go to receptions, embassies in Copenhagen, especially the Belgian embassy because they have a lot of African diplomats coming there. I noticed all the telltale signs, the do’s and don’ts of how diplomats behave and carry themselves. For instance, when they’re having cocktails they like to fold their napkin into a triangle and then wrap it around the glass. I think it’s because they don’t want to leave fingerprints, but I don’t know for sure. [Laughs.]

The most popular cigarette amongst African diplomats are red Dunhills. The most popular liquor is Johnny Walker Black Label. You know, things of that order. At the same time, I also wanted my ‘character’ to be packed with various archetypes, and characters from comic books: Dr. Müller in Tintin, Bernard Prince (a Belgian comic book hero), even the Man with The Yellow Hat from Curious George.

Apuzzo: I thought that one of the key things that sold the character, so to speak, was his personal narcissism – in terms of the clothing, the demeanor, the portrait that you had of yourself in the diplomatic suite. Was that narcissism a key component of how you interacted with people there?

Murty: In other words, was that narcissism a way of interacting or seeming believable to people of the tyrannical mindset — since narcissism is a key element of tyranny?

Brügger: Exactly. There’s narcissism in it, but also: you know the theory about ‘mirror neurons’? That when you’re meeting somebody you start emulating them, on an unconscious level.

I think it played out well — that by looking like something from a Graham Greene novel from the ’60s or ’70s I would attract people who are on to the same fantasies that I display, which is what I think happened. I was the ultimate fantasy of a white businessman-diplomat, because Africans themselves also have fantasies about white people. Usually they deal with these scruffy-looking NGO guys in sweaty T-shirts. I thought that if I would look very rich, very well-off, very eccentric, I would make African ministers think: if he looks like that he has to be very rich, very powerful, probably also very naive and idiotic. But that’s OK. You know, ‘we will not kill him – we can use him.’ So there’s also a survival strategy in it.

Apuzzo: Two really key figures out of the whole film were ‘Dr. Eastman,’ who is this sort of secretive, shadowy European figure pulling the strings and selling the diplomatic titles – and also Emperor Bokassa [former dictator of the Central African Republic], whom you mentioned you had a personal fascination with.

Brügger: Yes, very much so.

Apuzzo: Emperor Bokassa representing the worst of 1970s-era African despotism …

Brügger: … and madness.

Apuzzo: And with ‘Dr. Eastman’ almost representing the European side of that madness, almost like an Ernst Blofeld or a Bond-villain.

Brügger: Exactly.

Apuzzo: It seemed that what allowed you to get away with what you did was that you were fulfilling stereotypes and fantasies that a lot of Africans themselves had about white European businessmen.

Brügger: Yes, it has a lot to do with ‘magical thinking,’ which is something very important in Africa. Bokassa, as you know, he was the ultimate expression of this particular kind of madness. He was this carnivalesque figure trying to emulate Emperor Napoleon. He had this Napoleonic coronation, costing the national GNP times one hundred.

Murty: You had some footage of it in the film.

Brügger: Yes, it really is unbelievable. That, of course, also has a lot to do with this very painful relationship of the ‘colonial master’ with its subject.

What’s so interesting is that there is this Werner Herzog film called Echoes from a Somber Empire, and he went in the early ’90s to the Central African Republic together with a journalist named Michael Goldsmith, who was almost beaten to death by Bokassa, personally. And they go back to re-track the history of Bokassa – and at the end of the film, we learn that Michael Goldsmith is now dead because he had gone to Liberia to cover the civil war where he gets killed. So there are some very interesting intertextualities between [Herzog’s] film and my film.

Murty: You briefly alluded to Conrad’s Heart of Darkness in the film. You said that if the Congo is the ‘heart of darkness,’ then — and you put a humorous twist on it — then the Central African Republic is its ‘appendix.’

Brügger: Yes, exactly.

Murty: So much of what Conrad depicted seems to still be existing in Africa today, over a century later. Were you consciously thinking of Conrad and what he depicted as you set out on your own journey?

Brügger: Look at the Head of State Security [the obese ex-French Legionnaire shown in the film]. He’s like Marlon Brando in Apocalypse Now. He is in ‘the horror,’ you know. […]

It’s a total dog-eat-dog world, and the new boss on the block is definitely going to be the Chinese. They are all very worried about the Chinese. They were personally telling me, you know, ‘be careful about the Chinese.’ And I would ask, ‘but where are they?’ ‘Are they here at all?’ And they would say, ‘yes, they are here — but they are very sneaky. We never see them, but they are here.’

Apuzzo: I wanted to ask you about that, because there was a statement you made in the middle of the film about a ‘new Cold War’ between the U.S. and China. You’re obviously very concerned, having done The Red Chapel, with communist tyrannies, and so forth. Do you actually think there’s a coming Cold War between the U.S. and China?

Brügger: I think that could very well be. Just look at what China’s doing now in the Pacific … and the scale of what they’re doing in China is mind-blowing — how much money they’re bringing in, how many natural resources they’re bringing in. They’re bankrolling, for instance, Mugabe — who is like an African Hitler, basically. He is the devil incarnate. By buying his diamonds, they keep his regime going — which is criminal, I think.

For me, the defining moment with Sino-African politics is China inviting [Sudanese President] Omar al-Bashir to Beijing. He is a wanted criminal, wanted for crimes against humanity [the Darfur genocide], and yet they take him to Beijing and treat him with a state banquet, which is really depraved. And for sure there are tensions in Africa between the West and China, and they will become worse, I believe.

Apuzzo: Changing subjects, there’s this idea we have in the West nowadays that it is the West that is exclusively victimizing Africa. And you depict quite a bit of that in your film, obviously. But it seems that the breakthrough of your film is in showing how through these despotic tyrannies Africans also victimize themselves.

Brügger: About 8 million people were killed during the time of Belgian rule, but what is going on today has a lot to do with what Africans are doing to themselves. Also, you know, they have this ‘zero-sum’ thinking. So if it’s going well for you, an African would tend to believe ‘something is going wrong for me.’ It’s not possible for you to do good, without somebody else doing bad. So they will start to envy you, and hate you. And that kind of thinking, you know, really destroys a society.

Murty: One of the other things that was heartbreaking was that scene where M. Gilbert is being confronted by his wife at the diamond mine. There’s some sort of a fracas, and he says: “don’t shame me in front of the white men.” That was a very interesting moment, that there’s still this sense of inferiority vis-a-vis ‘white’ culture, and a feeling of subservience, and how that mindset is hard to break.

Brügger: It has to do with how complex a thing racism is in Africa – because there’s white vs. black racism, but there’s also black-on-black, black-on-Chinese, blacks being racist toward white people …

Apuzzo: Tribal rivalries …

Brügger: … tribal rivalries, which are also tearing countries apart. So it [racism] is really a very sinister thing in Africa.

Apuzzo: I want to ask you about your relationship with the pygmies. [Brügger employs members of a pygmy tribe to work in a match factory that will serve as the cover for his attempted diamond smuggling in the film.] What was that actually like behind the scenes?

Brügger: Pretty much as it was in the scenes. Actually, I think they were severely damaged from binge drinking. They do drink a lot, the pygmy people, at least in the vicinity of Bangui. But we were, of course, worlds apart. There wasn’t much that connects me with a pygmy. What is there to talk about, you know?

Apuzzo: Let me tell you something that I found interesting about their [the pygmies] presence in the film — that reminded me of something in The Red Chapel. In The Red Chapel you went over to North Korea with the handicapped comedian, Jacob Nossell — and the thing that occurred to me watching The Ambassador was that you were actually depicting in both films how handicapped people, or the weak, the infirm — how they end up being treated in these despotic societies. The way that the pygmies were outcasts from society, just the way your friend Jacob was treated in North Korea.

Brügger: That’s true. When North Korean people met Jacob, in that regard he was like the black swan. They would ask him if he was drunk, or if he was sick, because they’d never seen a person with his kind of handicap before. As with Albert and Bernard [the pygmies in The Ambassador] and with pygmies in general, they are outcasts, they are abused, they are looked down upon, there’s a lot of racism regarding pygmies. And there are these horrible occurrences in the Congo where rebels have killed and eaten pygmies – it’s atavistic, to get part of their ‘magical powers’ inside them. So, you know, the ones paying the highest price for dysfunctional African states are the pygmies.

Murty: It’s interesting how so often in societies that live according to mythological thinking the outcast figure — the sacrificial figure, as it were — is also considered the figure who can bring magic, and who must be controlled or exploited in some manner. I guess the pygmies were those figures in that community. I just feel very sad for the pygmies, themselves. […]

You also bring up the fact that it’s next to impossible to do business there. For people who are well-meaning, Western people who want to do development in Africa and help — the whole idea of development being that you don’t give people hand-outs, but you build things so they can run them themselves …

Brügger: That doesn’t work there.

Murty: Is there any hope? How will things improve there?

Brügger: I think it’s a situation of utter despair. Some of the diplomats in Bangui told me they believed that within the vicinity of 15 or 20 years the country will no longer exist, because they can barely uphold their own sovereignty. They only have two thousand soldiers to protect an area the size of Texas. They have the Lord’s Resistance Army there – this crazy, border-crossing, rebel group headed by a transvestite wizard called Joseph Kony. You have two or three different rebel groups. You have highway robbers from Chad.

Apuzzo: On that point I wanted to ask you something that was touched on in the film – the possibility of M. Gilbert’s terrorist ties or connections …

Murty: … to an organization that was one of the funders of Hamas.

Apuzzo: What did you make of that?

Brügger: Hassan el Bakas? Well, I discovered for sure that Hassan el Bakas exists, and he’s a real figure, so that checked out — what the State Security guy was saying. And that he is a very shady and sinister guy. […]

Apuzzo: Who are your favorite filmmakers?

Brügger: Werner Herzog, of course. A Swedish director called Roy Andersson, he’s not very well known outside of Scandinavia. Lars von Trier, he’s really a master. Todd Solondz. I like his sense of humor; I really like the film Palindromes — I think it’s his best film ever.

Murty: What about classic Danish filmmakers? For example, Benjamin Christensen in the ’20s made Haxan/An Account of Witchcraft and Magic through the Ages, and then also Dreyer, The Passion of Joan of Arc …

Brügger: Of course Dreyer is on my list, you know, he was probably the biggest Danish filmmaker ever.

Apuzzo: This is the second film in a row you’ve done, the purpose of which is to expose corruption. Is that how you conceive your mission as a filmmaker and as a journalist?

Brügger: Of course, journalism and humanism go hand in hand. And I think of them as very humanistic films- – almost to a spiritual level.

Murty: In your films, underneath all of your satire, and your exposure of the horror of what you’re seeing — you have a deeply humanistic vision, a sense of outraged morality at your core. Of course, coming from northern Europe, there’s a humanistic tradition that goes back to Erasmus … I see your films and I also think of paintings by Brueghel or by Hieronymus Bosch in terms of the grotesque human behavior you expose. Do you see yourself as part of that tradition?

Murty: In your films, underneath all of your satire, and your exposure of the horror of what you’re seeing — you have a deeply humanistic vision, a sense of outraged morality at your core. Of course, coming from northern Europe, there’s a humanistic tradition that goes back to Erasmus … I see your films and I also think of paintings by Brueghel or by Hieronymus Bosch in terms of the grotesque human behavior you expose. Do you see yourself as part of that tradition?

Brügger: Well you know [looking abashed], I don’t think of myself in terms of Brueghel and the classic painters, but Denmark is in many ways the ultimate expression of humanism — which you can also feel in the way Danish people trust the state. Danish people believe that people of authority are like The Smurfs. Benevolent people. [Laughs.] But that is because there is so much trust among citizens in Denmark, among citizens and the authorities. It’s one of the least corrupt societies in the world, you know.

At the same time, it’s also a very matriarchal society. Most of the schooling system, the universities, are defined by and led by women. And this creates a situation in which a lot of men of my generation have problems with authority. I sure do. That also in many ways defines the kind of journalism that I do.

Murty: Were there other things in your upbringing that shaped your particular vision as a filmmaker – in terms of either you family, or your education?

Brügger: Well of course my mother and father being journalists … My father was the editor-in-chief of Denmark’s biggest business daily, the Financial Times of Denmark, while my mother worked for twenty years at Denmark’s biggest tabloid, exposing scandals about politicians. In some ways I am a synthesis of this – the tabloid/yellow press thinking, and the more traditional business journalism. In a way, it is a strange mix of Borat and The Economist.

Murty: You mentioned the humanistic vision of your films – but also about the spiritual element, as well. What is your own spiritual inspiration as you tackle these very difficult subjects?

Apuzzo: In other words, what sustains you as you descend into hell?

Brügger: [Laughs.] In Danish we have an expression, “to do the white cut.” That is a Danish expression for a lobotomy. It is also a metaphor, to “give yourself the white cut.” … It’s an act of letting everything else go. Just doing it.

Murty: Almost like a Zen-type moment. Entering the void. Losing your mindfulness.

Brügger: Yes, going ‘all-in.’ Without any considerations of what will happen to you, what will happen to other people, just doing it. So when I’m in it, I’m ‘all-in.’

Published on February 10th, 2012 at 8:15am.

Great interview. Liked Brugger before; like him even more now.

I caught Red Chapel on netflix and it is hands down that best thing I’ve ever seen on North Korea, and I’ve seen most of them. Can’t wait to see this one; hope it gets out on DVD soon.

I too think Palindromes is Solondz’s best film.

Thanks, SeeSaw. Believe me, if you liked Red Chapel you’ll love The Ambassador even more. It’s really incredible.

@SeeSaw – If you liked RED CHAPEL, you should check out the VBS guide to North Korea: http://bit.ly/mSXy1v