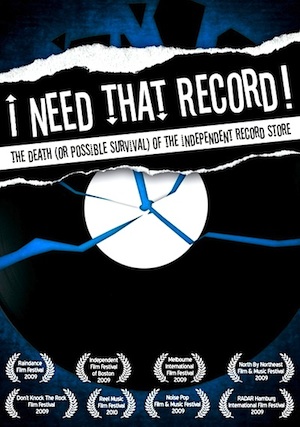

By David Ross. Brendan Toller’s documentary I Need That Record! The Death (or Possible Survival) of the Independent Record Store (2010) brings a good deal of personality and attitude (in the best sense) to the story of the demise of the independent record store, though it might just as well tell the story of the demise of the independent video or book store, all of which are victims of the same forces: box store encroachment followed by on-line revolution, all feeding the bottom lines of large corporations that don’t particularly give a damn about records, or movies, or books. The restaurant business has been similarly decimated. Applebee’s anyone?

I am a fierce advocate of free-market capitalism, and yet I have to agree with Toller that something has gone wrong when Wal-Mart sells 20% of all albums and those albums are largely the work of corporate mannequins like Lady Gaga and Justin Bieber. My mid-sized Southern college town has one remaining used record store and one remaining used book store. Our last independent video store closed in December, and our Borders – which drove out our independent book and record stores – recently got a dose of its own medicine and closed amid a blaze of luridly florescent signage of the kind you associate with particularly tacky used car lots.

I’ll have to explain to my young daughter how likeminded people used to gather – in the flesh – to mingle, swap notions and preferences, and listen to whatever was on the turntable. I will have to recreate the lost world of my youth, and tell how I roamed the second-hand record stores of Boston and Cambridge, spending hours in grungy mouse-holes like Mystery Train (named in honor of the Elvis tune), and how I timidly put my fourteen-year-old inquiries to the superior wisdom of pierced twenty-four-year-olds, who had, in fact, heard everything and evolved a real critical acumen. Between 1988 and 1992, I spent many procrastinative late afternoons at Cutler’s in New Haven (still there!). I once asked the sagacious manager about Moby Grape’s first album, about which I’d read in The Rolling Stone Record Guide (before it annoyingly became the “album guide”). He said that the record was out of print but that he had a copy (of course) and that he’d make me a tape. My tape was waiting for me the next day, as promised. You don’t get that kind of service – that degree or any degree of giving a damn – at Wal-Mart.

I will have to convey to my daughter what an elegant physical object the long-playing vinyl record was: how heavy as it balanced on the fingertips, how mysteriously engraved, hypnotic in its rotation, poignantly delicate and prone to time’s different kind of engraving.

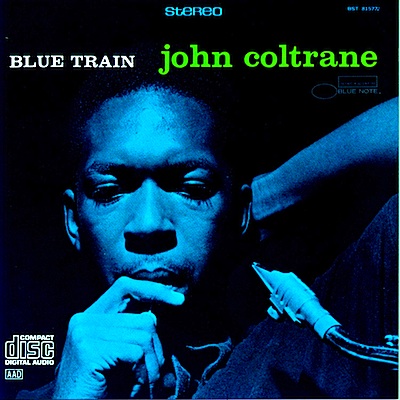

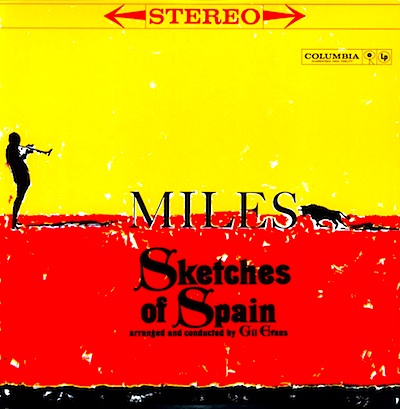

Explain also how eye-catching and sometimes beautiful album art was and how much the art mattered. Certain album covers were indelible objects of fascination. Blue Note’s myriad masterpieces of cover design (see here) seemed to inscribe a whole worldview of avant-gardism and cool, a kind of visual code for high modernism in its African-American dimension. On more sober and mature reflection, I realize that Blue Note created one of the supreme caches of modern American design. I adored the Warhol banana on the first Velvet Underground album (1967) and the Mapplethorpe portrait on Patti Smith’s Horses (1976). It’s reasonable to surmise that album art, like comic books, filled a gaping visual void in middle-class American life and inspired countless young people to begin to think about the world in visual terms.

I will also have to explain that technology is not necessarily progressive and that the long-playing record actually sounded better.

I will have to explain, finally, that each record somehow told the story of its own history. In I Need That Record, Lenny Kaye, Patti Smith’s guitarist, beautifully elegizes the LP as an artifact in this sense:

I’m a fan of the download. I like to hit enter and have the song appear on my iTunes within seconds, but there’s something about holding the artifact, about feeling it in your hand. It reveals a lot about the moment in time that the record was made. An abstract song could come from anywhere, but if you see something in a twelve-inch vinyl LP, with the cover art, or you hear the scratch in the 78, you get a sense of time and place that is, for me, irreplaceable.

When my daughter asks what happened to record companies and record stores and to the records themselves, I will have to answer honestly, “I’m not really sure.” Communism is a potential analogy: decades of self-imposed misery, the illogic of which was demonstrated by the almost instantaneous evaporation and repudiation of the offending system. Does capitalism have phases of communistic heartlessness and aimlessness and self-destruction? Perhaps we too will eventually exclaim, “Good lord, what are we doing to ourselves,” and our equivalent of the Berlin Wall will suddenly become the pile of rubble it was, in actuality, all along.

Fred Goodman’s classic The Mansion on the Hill: Dylan, Young, Geffen, Springsteen, and the Head-on Collision of Rock and Commerce is a good place to begin an inquiry into what the hell has gone wrong (1998). I Need That Record updates the story.

Digital media have partially loosened the bottleneck created by the record companies, but on-line existence is comparatively sterile and un-educational in the broadest life sense. It’s great to watch, say, Wanda Jackson or Hound Dog Taylor on YouTube (here and here), but there’s no getting around the fact that you remain at your desk, not having had to foray into the world of sights and sounds and chance encounters. And, in any case, where are today’s Wanda Jacksons? Where are the A&R men and independent record store owners working on behalf of the next Wanda Jackson, not because they want a spread in the Hamptons, but because they instinctively want to live in a world that’s a little more spirited?

Posted on May 27th, 2011 at 9:18am.

Is it possible that running these “independent”, less-profitable types of shops an services has become much more difficult because of increased business and employment regulations, taxes and charges, insurance premiums, etc.?

A year or so ago I attended the screening of a short documentary film about the decline of an independent film venue in Australia.

There was much lamenting during this soppy, nostalgic film about the big end of town, the decline of standards, and the unmatchable, “unbalanced” power of commercial cinema. (i.e. the sort of baloney you might get from someone like Chomsky.)

After the film was … finally … over … I asked the filmmaker, who was there to answer questions, about such matters as insurance charges, taxes, union regulations, etc. and whether or not he’d found that they had contributed to the decline of this small, enthusiastic venue.

In other words, although I didn’t phrase it explicitly in such terms: What about anti-free-market factors?

Lo and behold, all these factors turned out to be MAJOR contributors in the decline of this “independent” film venue!

But they weren’t mentioned during the documentary, and probably wouldn’t have been mentioned by the audience had I not brought up the issue.

I hope the connection between this story and the review by David Ross is clear.

Capitalism (separation of state and economy, limited government, etc.) is good for the independents which tend to run on a shoe-string. And statism is disastrous for the independents.

Best Wishes,

PRODOS

Melbourne, Australia

Prodos,

You ask a fascinating un-asked and un-answered question. My sheer speculation is that taxation are regulation are not the crux of the problem. The crux of the problem is that clientele is shopping elsewhere, and more basically that the culture is not producing enough people who instinctively say “No thanks” to the brave new world of Wal-Mart and i-Tunes.

Only a few even try to say “No thanks.” At my daughter’s K-12 school, I have the chance to witness the fringe kids with their florescent dyed hair and multiple piercings and obscure totems that refer to even obscure bands. I respect their impulse resist the culture of the Box Store and give them a degree of credit, but their retort to this culture seem so shabby and brainless. They do not realize that the reverse principle of the Box Store is not punk music or skateboard or tattoos, but Beethoven.

I don’t know what part of the country you hale from, David, but here in California the mom and pop indie record stores got blown out of the water in the early 70s. Stores like Wherehouse and the Tower Records put them out business by massive corporate investment and concentrating on the top 90 percent popular product while ignoring the outlying 10 percent. If you were a collector and enthusiastic enough, you could go to the semi-annual record collector conventions to find what you wanted – usually at a large premium.

Ironically, Wherehouse was killed by Tower, and Tower was killed by the internet – and vinyl collecting has moved to EBAY.

With the death of Tower Records a few years ago the final nail was put into the coffin for these eclectic type of stores.(although that was a mutli-store Big Box that was able to have that indie feel) I honestly miss them because as it points out there was a sense of community and discovery. I’ve substituted them to a degree with Amazon. But still, the sense of discovery is missing. The only quibble I have with this movie (I literally groaned) was the shot of President Bush with a IPOD and the commentary that even a moron can operate them. It was unnecessary and gratuitous. And with that shot and commentary it reminded what I didn’t like about these type of stores and that’s the type of people that typically worked at them. For the best representation of that type of personalty look no further than the Jack Black character (Barry) from the movie, High Fidelity.

Great job, David — it’s nice to see these types of establishments and moments romanticized like this. I never really got into the indie music store scene because Best Buys and Wal-Marts popped up everywhere when I was in high school.

I still get a taste of this experience at my local comic book store — a place that remains a bastion of reality never covered by the facade of soulless corporatism. It’s somehow refreshing to get a small roll of the eye from the guy behind the counter when I plop down my Star Wars and Green Lantern books, which obviously aren’t hip enough to be taken seriously.

Usually conversations evolve into political debates, but in those environs, I can unleash a verbal fury. At work I have to be a little nicer … a little.

I’d love to see Toller’s piece.

I’ll echo a previous poster’s comment about the gratuitous shot at Bush. An encouraging sign, though, is the fact that vinyl still exists and continues to grow in sales each year. I work at a high end home entertainment store, and we sell all the latest in digital technology, but we also have a steady stream of sales of turntables and analog accessories. Quality is still around, albeit a little less visibly. You just need to seek it out. The point in the article about the loss of community is one, though, that isn’t as easily remedied.

Some of the dilemma is generational. The people that aged out into retirement in the 1970s, 80s, into part of the 90s were able to keep a big chunk of non-rock popular music going, and their spending coincided with the rock and roll record buyers. That’s a pretty good sized audience when combined. (I remember classical-music only record stores that were surviving in larger cities, and there were other mixed-specialty shops abounding too). But those old people stopped buying because they were dying off, and they took a lot of their pop culture with them, besides just their money. Rock and roll just isn’t big enough, and it was the perfect genre (along with modern pop, rap, etc) to get wiped out by (the original) Napster and all the others that have followed. My opinion, for what it’s worth, is that the WW2 generation that funded the huge growth of pop culture that rock-and-roll eventually co-opted, would not have supported the illegal downloading phenomenon. So, my theory is part of the audience that funded the breadth and depth of pop music died off, and the fans left are too easily able to make the compromise of simply stealing recorded music. Another coffin nail is that most teen/twenties people today do not want physical objects like CDs, they want the gadgets that play the recorded music, organizes it, and lets them control it in a way no automatic turntable ever could. It isn’t that it is “un-hip” to buy a CD, its just pointlessly old-fashioned, even anti-economic, because what if you only want the one song and don’t like the rest of the ‘album?’ Something which generations of platter buyers accepted as a cost of getting what you want is now superfluous. There are many more reasons, like a “perfect storm” of reasons, why the music industry has had to take it in the gut, diminishing into a fraction of what it once was. But I believe it starts with the WW2 generation going offstage.