By Joe Bendel. If you are looking for a unifying theme among this year’s live action short film Oscar nominees, several address the responsibilities of parents and the extent to which the wider society can complement or replace the family unit. Of course, there is also the ringer that cannot be shoehorned into a handy rubric. All five nominees screen as part of the annual showcase of Academy Award nominated shorts, which opens today at the IFC Center in New York.

Frankly, Sini and Jokke are not bad parents. They are just kind of a mess in Selma Vilhunen’s Do I Have to Take Care of Everything? Nearly over-sleeping an important wedding, they still manage to schlep their two young daughters over to the chapel, despite a series of minor disasters. Everything is pleasant and amusing, but only an inch deep and seven minutes long.

In contrast, Esteban Crespo’s That Wasn’t Me seems to expect a round of applause just for dramatizing the child-soldier issue. Married Spanish doctors have come to an African war zone as part of a humanitarian mission, but their safe passage documents do not impress one warlord. The horrific crimes that follow will be done at his behest by young orphans pressed into his so-called army. Discussing his crimes after the fact, one former child-soldier explains how the guerilla commander exploited their need for a sense of family and belonging.

There are scenes in TWM that are genuinely shocking. While it serves as a timely reminder of the appalling lack of human rights throughout the continent, the film feels rather programmatic, like a calculated statement rather than a fully realized drama in its own right.

When it comes to pulling on heartstrings, none of the shorts can compete with Anders Walter’s Helium, but earns its sentiment through honest hard work and artistry. Alfred’s parents are caring and conscientious, but that cannot change the fact he is dying of a terminal disease. His mother constantly tells him he is going to Heaven, but the harps and white robes do not do much for him. Enzo, the clutzy new janitor, has a better conception.

Reminded of his late kid brother, who also shared a love for zeppelins and Jules Vernish hot air balloons, Enzo starts telling Alfred about the world of Helium, a steampunk-Boy’s Life alternative to Heaven. For a while, Enzo’s vision of Helium lifts the boy’s spirits, but his body soon takes a turn for the worse. Helium’s animated fantasyscapes are quite richly rendered, bringing to mind about the only part of the What Dreams May Come movie that actually worked. However, it is the chemistry between Casper Crump, Pelle Falk Krusbæk, and Marijana Jankovic as Enzo, Alfred, and his understanding nurse that really lowers the boom in Helium. Despite the melodramatic aspects, viewers will feel moved rather than manipulated.

Reminded of his late kid brother, who also shared a love for zeppelins and Jules Vernish hot air balloons, Enzo starts telling Alfred about the world of Helium, a steampunk-Boy’s Life alternative to Heaven. For a while, Enzo’s vision of Helium lifts the boy’s spirits, but his body soon takes a turn for the worse. Helium’s animated fantasyscapes are quite richly rendered, bringing to mind about the only part of the What Dreams May Come movie that actually worked. However, it is the chemistry between Casper Crump, Pelle Falk Krusbæk, and Marijana Jankovic as Enzo, Alfred, and his understanding nurse that really lowers the boom in Helium. Despite the melodramatic aspects, viewers will feel moved rather than manipulated.

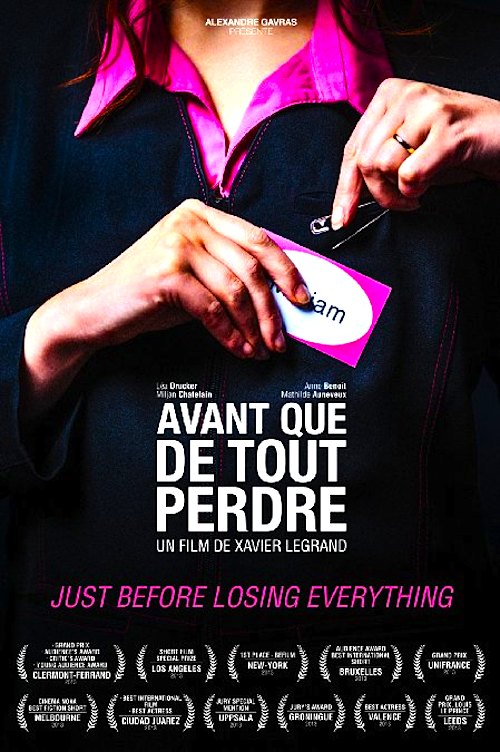

There is also some pretty raw emotion in Xavier Legrand’s Just Before Losing Everything, which is arguably the best of this year’s live action nominees. Miriam is a battered wife, who has finally decided to leave her husband. However, it will not be a simple matter of walking out the door. She must bundle up her kids and collect what money she can from the job she must leave behind. Everyone at her Tesco-like superstore is sympathetic, but uncomfortable and unsure how far they can go to help. Then her husband shows up looking for the checkbook.

If Helium boasts the strongest ensemble of this year’s nominations, Losing features the single strongest performance from Léa Drucker as Miriam. We so get all her fear, vulnerability, and misplaced shame. Instead of yelling “look at me,” it is work that hits you in the gut.

As the odd man out, Mark Gill’s BAFTA nominated The Voorman Problem tells a self-consciously clever tale of an emotionally disturbed prison inmate who thinks he is the almighty and the nebbish shrink sent to evaluate him. There is witty bit of business involving Belgium, but the ironic payoff is forced and perfunctory. Nonetheless, co-star Martin Freeman has helped generate scads of revenue for the industry as Bilbo Baggins in the Hobbit trilogy and Watson in BBC/PBS’s Sherlock, so Voorman might have the inside track with the Academy.

In terms of tone and overall quality, this year’s live action field is less consistent than their animated counterparts. Still, it is well worth seeing for Helium and Just Before Losing Everything, which account for over half the program’s running time. They introduce some international talent worth keeping an eye on. Recommended accordingly, the nominated live action showcase opens today (1/31) at the IFC Center.

Posted on January 31st, 2014 at 2:04pm.