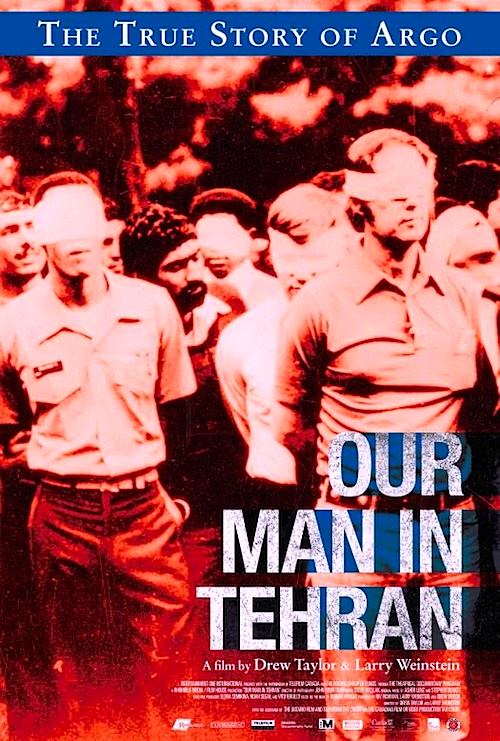

By Joe Bendel. The word “diplomatic” is often used as an adjective for cautious and noncommittal. That hardly describes Canadian Ambassador Ken Taylor’s term of service in post-Revolutionary Iran. He was the one played by Alias’s Victor Garber in Argo. As Hollywood films go, it was pretty accurate, but there was considerably more to the story. Co-producer-directors Drew Taylor (son of Miracle Mets pitcher Ron Taylor) & Larry Weinstein tell the behind-the-scenes story of the ambassador, his wife Pat, and his diplomatic staff, as fully as it can now be told, in Our Man in Tehran, which opens this Friday in New York.

When the Islamist students occupied the American Embassy with the Ayatollah’s blessing, it constituted a direct act of war. It also sent a chill through every other western mission. Somehow, six consular officers managed to slip out the back alley, but they were cut off from the British Embassy, their designated emergency refuge. It would be Ken Taylor and his colleague John Sheardown who took in the Americans, literally hosting the six “Houseguests,” as they came to be known, in their private residences.

Yes, there was a CIA agent named Tony Mendez who developed and implemented a daring plan to extract the Houseguests. Perhaps you have heard about it. The cover story involved a phony science fiction film titled Argo. If you haven’t, Mendez himself takes viewers through the operation step-by-step. However, one of the greatest revelations in OMIT is the extent to which the Ambassador and embassy personnel were gathering and relaying intel for the tragically ill-fated rescue attempt.

As much as former “October Surprise” conspiracy theorist Gary Sick tries to cover for his former boss, Jimmy Carter comes off looking like a bumbler out of his depth dealing with the Iranian crisis. Yet, in retrospect, nobody looks worse than Canadian opposition leader Pierre Trudeau, who tried to exploit the situation asking combative questions he knew from confidential briefings with PM Joe Clark that External Minister Flora MacDonald could not safely answer.

As much as former “October Surprise” conspiracy theorist Gary Sick tries to cover for his former boss, Jimmy Carter comes off looking like a bumbler out of his depth dealing with the Iranian crisis. Yet, in retrospect, nobody looks worse than Canadian opposition leader Pierre Trudeau, who tried to exploit the situation asking combative questions he knew from confidential briefings with PM Joe Clark that External Minister Flora MacDonald could not safely answer.

The access to primary sources in OMIT is rather remarkable, with (Drew) Taylor & Weinstein scoring extensive on-camera interviews with both Ken and Pat Taylor, as well as Clark, MacDonald, Mendez, Sheardown’s widow Zena, the Houseguests, and former Iranian hostage and CIA station officer William Daughtery. Indeed, it is quite valuable to have the perspective of Daughtery, who probably endured the worst torture meted out by the Revolutionary Guard during the hostage crisis. However, it is a little awkward seeing the discredited Sick pop up periodically, even though he avoids making unsupported accusations this time around.

The accounts surrounding Argo and the Houseguests are absolutely fascinating and inspire warm feelings of fellowship for all Canadians (except Trudeau). With co-writer Robert Wright (author of the eponymous book on which OMIT is based), Taylor & Weinstein give the audience a detailed understanding of the rituals of diplomacy and the secret inner workings of the intelligence services. There are also real lessons to be learned from the incidents it documents. First and foremost, wishful thinking is not a strategy. Highly recommended, Our Man in Tehran opens this Friday (5/15) in New York, at the Cinema Village.

LFM GRADE: B+

Posted on May 12th, 2015 at 10:52pm.