By David Ross. I offered a little paean to the independent film here, but what would such a paean to the contemporary Hollywood comedy look like? The Hollywood comedy is, if not dead, at least writhing on the floor and gasping for breath and rapidly turning blue. Netflix’s selection of new comedies is a flotilla of cliché-ridden, two-starred dreck, of which a film like You Again (2010) is representative. Kristen Bell, Jamie Lee Curtis, and Sigourney Weaver head a mildly promising cast, but the film is a mire of clichés. Here’s the plot in Netflix-speak:

History – make that high school – may repeat itself when Marni (Kristen Bell) learns that Joanna (Odette Yustman), the mean girl from her past, is set to be her sister-in-law. Before the wedding bells toll, Marni must show her brother that a tiger doesn’t change its stripes. On Marni’s side is her mother (Jamie Lee Curtis), while Joanna’s backed by her wealthy aunt (Sigourney Weaver).

Every character is a deliberate incarnation of cliché: the nerd-turned-LA-public relations-whiz-who’s-still-a-nerd-at-heart, the head cheerleader who sadistically delights in tormenting her social inferiors, the salacious granny who says things like “If you don’t go for him I will” (this an attempt to reverse the eighteenth-century cliché of Mrs. Grundy, never mind that this cliché was killed off decades ago, possibly by Auntie Mame), the eye-rolling, wise-ass younger brother whose sarcastic sallies are affectionately disregarded. And of course the film ends with psychotherapeutic reconciliations and teary hugs. Comedy depends on surprise and sudden anarchic subversion. Cliché is anathema to surprise and the reverse of subversive. Thus a film like You Again is, by definition, dead on arrival.

I’m interested in You Again only as an example of the countless comedies that go quietly to the doom of bored trans-Atlanticists who watch thirty minutes and decide to snooze or fiddle with their iPhones. Movies like this don’t even bother to resist their fate; they may even seek it on the principle that formulaic death-in-life is less culpable than risk.

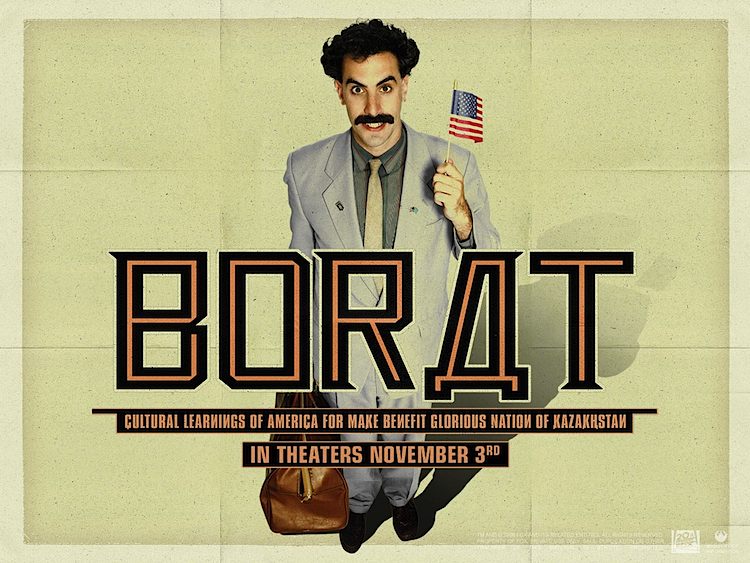

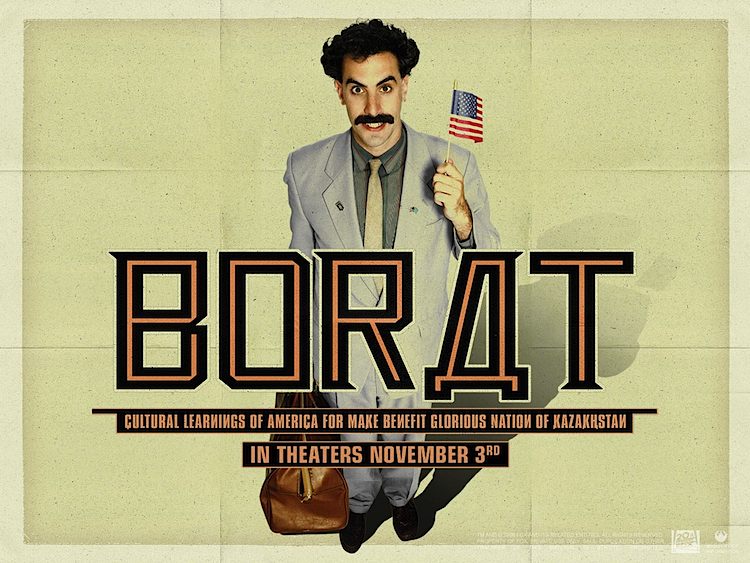

Genuinely funny films like David O. Russell’s Flirting with Disaster (1996), the Coen brothers’ Intolerable Cruelty (2003), Borat (2006), and Greg Mottola’s Superbad (2007) are exceptions that prove the rule. Ben Stiller in Flirting with Disaster reminds us of Ben Stiller in Zoolander, Dodgeball, Envy (don’t even remember this stinker, do you?), Starsky and Hutch, Night at the Museum (1 & 2!), The Marc Pease Experience, and so forth. Jonah Hill in Superbad reminds us of Jonah Hill in calibrated conventionalities like Knocked Up, Saving Sarah Marshall, and Get him to the Greek. Rowan Atkinson in Black Adder – perhaps the funniest turn in all of contemporary comedy – reminds us of Rowan Atkinson in The Lion King, Johnny English, and Mr. Bean’s Holiday.

Genuinely funny films like David O. Russell’s Flirting with Disaster (1996), the Coen brothers’ Intolerable Cruelty (2003), Borat (2006), and Greg Mottola’s Superbad (2007) are exceptions that prove the rule. Ben Stiller in Flirting with Disaster reminds us of Ben Stiller in Zoolander, Dodgeball, Envy (don’t even remember this stinker, do you?), Starsky and Hutch, Night at the Museum (1 & 2!), The Marc Pease Experience, and so forth. Jonah Hill in Superbad reminds us of Jonah Hill in calibrated conventionalities like Knocked Up, Saving Sarah Marshall, and Get him to the Greek. Rowan Atkinson in Black Adder – perhaps the funniest turn in all of contemporary comedy – reminds us of Rowan Atkinson in The Lion King, Johnny English, and Mr. Bean’s Holiday.

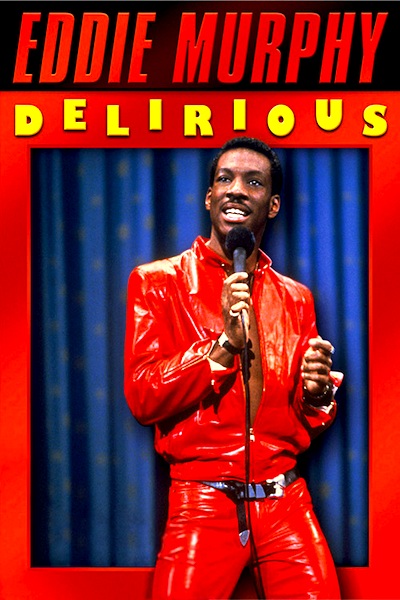

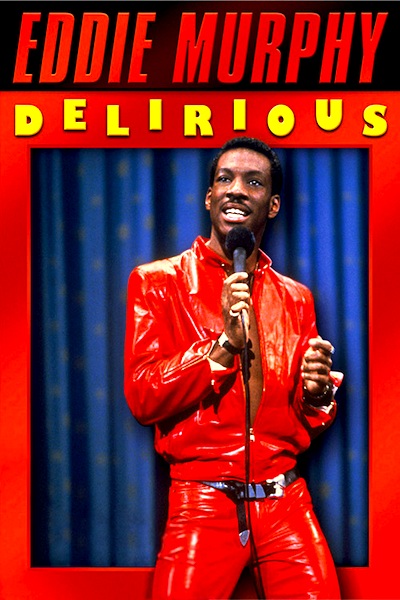

In the last twenty or thirty years, Hollywood has spent billions of dollars on comedies that have produced a few sniggers among thirteen-year-olds, but left this rest of us with a sense of having been gypped and maybe even insulted. It has also serially wasted the talents of generations of not untalented comedians. To those mentioned above, we can add countless others, beginning with Eddie Murphy, a legitimate comic genius (v. Delirious) reduced to whooping it up with barnyard animals. How does this happen?

A comprehensive explanation probably has a few components. There is of course the quest to hedge one’s bets and play it safe, which is part of the innate economics of the modern film industry, in which star vehicles begin $10 or $20 million in the salary hole. There is also the coarsening of the film audience along with the rest of the culture. Verbal high-wire acts like Ball of Fire and His Girl Friday assume audiences conditioned by the mordant witticisms of Mencken and the bright sophistication of Broadway show tunes and the lively bloodsport of cities with numerous daily newspapers. Audiences reared on video games and public school political correctness tend to go glassy-eyed while trying to follow a baseline rally of ironic badinage. Here’s a test: show a young person “Duck Amuck,” the most manic and zanily postmodern of the Loony Tunes. I bet they don’t laugh. Continue reading Whither Comedy?

By David Ross. Two propositions about James Brown: 1) He was the highest energy performer ever. In full overdrive, he was the rubber-legged soul incarnation of Chuck Jones’ Tasmanian Devil. Nobody – not Elvis Presley, Jimi Hendrix, The Who, or Bruce Springsteen – ever approached Brown’s expenditure of calories per second or approximated his capacity for what amounts to self-detonated metabolic nuclear explosion. 2) His bands of the late fifties and sixties – featuring vocal backup by the Famous Flames and best captured on the classic album Live at the Apollo (1963) – were the greatest of the R&B and rock era. These bands were not necessarily the most gifted, but they were the best rehearsed, the most cohesive, the most rhythmically agile, and in all ways the most pinpoint. The most virtuosic rock units – The Who, The Jimi Hendrix Experience, Led Zeppelin, Mahavishnu Orchestra, The E Street Band – sound tattered in comparison. While the rock ethos tended toward drug-induced laziness, Brown was an obsessive-compulsive Karajanesque whip-cracker, as his sixties-era sax player Maceo Parker recalls:

By David Ross. Two propositions about James Brown: 1) He was the highest energy performer ever. In full overdrive, he was the rubber-legged soul incarnation of Chuck Jones’ Tasmanian Devil. Nobody – not Elvis Presley, Jimi Hendrix, The Who, or Bruce Springsteen – ever approached Brown’s expenditure of calories per second or approximated his capacity for what amounts to self-detonated metabolic nuclear explosion. 2) His bands of the late fifties and sixties – featuring vocal backup by the Famous Flames and best captured on the classic album Live at the Apollo (1963) – were the greatest of the R&B and rock era. These bands were not necessarily the most gifted, but they were the best rehearsed, the most cohesive, the most rhythmically agile, and in all ways the most pinpoint. The most virtuosic rock units – The Who, The Jimi Hendrix Experience, Led Zeppelin, Mahavishnu Orchestra, The E Street Band – sound tattered in comparison. While the rock ethos tended toward drug-induced laziness, Brown was an obsessive-compulsive Karajanesque whip-cracker, as his sixties-era sax player Maceo Parker recalls: