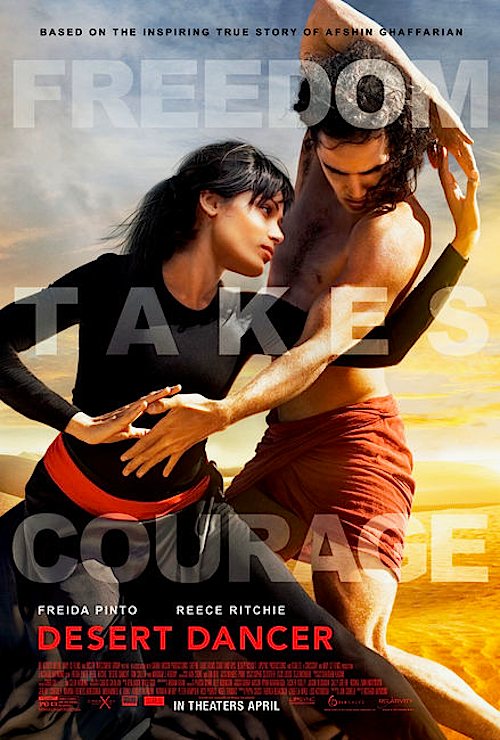

By Joe Bendel. “If you’re an artist, we’ll beat you artistically.” Yes, this is what passes for wit with the Basij, Iranian’s Islamist civilian paramilitary militia. Ironically, Afshin Ghaffarian got off relatively easily when a Basij chief spoke those words to him. Had he known Ghaffarian was actually a dancer, he most likely would have beaten him to death (quick, let’s make a nuclear deal with them). Ghaffarian and his friends were among the thousands brutalized by the Basij during the 2009 election protests, but they simply wanted to put on a public performance. Their brief moments of freedom are stirringly depicted in Richard Raymond’s based-on-fact bio-picture, Desert Dancer, which opens this Friday in New York.

Against all odds, Ghaffarian received clandestine arts education during his elementary years from a courageous teacher. He was a relatively experienced actor by the time he reached college, but his was always fascinated by the strictly forbidden discipline of dance. Of course, YouTube is duly blocked in Iran, but when he went online through a friend’s work-around access, he discovered a wealth of performances from the likes of Nureyev and Gene Kelly. Soon he convinces a handful of friends to join his proposed underground dance troupe. Everyone is understandable uneasy when the mysterious Elaheh invites herself into the group, but she turns out to be okay. She also has real technique, having been secretly trained by her former ballerina mother.

Longing to perform in front of a live audience, Ghaffarian and Elaheh will stage an intimate recital for a handful of carefully invited friends in a secluded desert location. Unfortunately, their friend Mehran’s older brother is a junior Basij commander, who is determined to ferret out Ghaffarian’s small ensemble. When another member is severely beaten by the Basij for his reformist allegiances, it puts further stress on the group. Soon Ghaffarian also finds himself be ruthlessly worked over in an unmarked Basij van. However, his fate will take a dramatic turn on the third act.

Longing to perform in front of a live audience, Ghaffarian and Elaheh will stage an intimate recital for a handful of carefully invited friends in a secluded desert location. Unfortunately, their friend Mehran’s older brother is a junior Basij commander, who is determined to ferret out Ghaffarian’s small ensemble. When another member is severely beaten by the Basij for his reformist allegiances, it puts further stress on the group. Soon Ghaffarian also finds himself be ruthlessly worked over in an unmarked Basij van. However, his fate will take a dramatic turn on the third act.

While the real life Ghaffarian has stressed the film’s thin layer of fictionalization, Raymond and screenwriter Jon Croker are scrupulously faithful to the tenor and circumstances surrounding the ill-fated 2009 Green Movement, as well as the general difficulties of being artistically inclined while living under a repressive regime. Desert is also closely akin to Bruce Beresford’s Mao’s Last Dancer (which won the Astaire Award for best film choreography) for the manner in which it portrays the powerful expressiveness of dance, while also using it as a symbol for freedom. In fact, Akram Khan’s choreography is unusually distinctive and Astaire Award-worthy, incorporating elements of ballet and modern interpretive dance.

To their estimable credit, co-leads Reece Ritchie and Freida Pinto clearly trained hard for their roles, because they do Khan’s steps justice. Frankly, when they are standing still, their romantic chemistry is just so-so, but when they move together, they heat up the screen. There are ably supported by a fine ensemble, particularly including the deeply humanistic performances of Makram Khoury, as Ghaffarian’s old teacher Mehdi, and Bamshad Abedi-Amin as the quietly courageous Mehran. It is also nice to see Nazanin Boniadi, albeit ever so briefly, in a near cameo as Ghaffarian’s progressive mother, Parisa.

Desert vividly captures the ominous atmosphere of the 2009 crackdown, as well as the liberating power of dance. In his feature directorial debut, Raymond maintains a tense, paranoid vibe, but also exhibits an intuitive sense for when to go for the emotional jugular. It is an inspiring story that is undiminished by the real life Ghaffarian’s recently more circumspect rhetoric. Enthusiastically recommended, Desert Dancer opens this Friday (4/10) in New York, at the Landmark Sunshine and the Loews Lincoln Square.

LFM GRADE: A-

Posted on April 6th, 2015 at 9:19pm.