By Joe Bendel. Thanks to Gustav Klimt’s Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer, art lovers around the world will instantly recognize Maria Altmann’s beloved aunt and her iconic choker necklace. After the annexation of Austria, Bloch-Bauer’s necklace found its way into the possession of Herman Goering’s wife, while her stunning portrait was plundered by Vienna’s Belvedere Gallery. For years, it was the cornerstone of their collection, but Altmann filed a restitution claim as the last surviving Bloch-Bauer heir that ultimately forced Austria to confront its National Socialist past. Altmann’s dramatic early years in Austria and her protracted legal battle are chronicled in Simon Curtis’s The Woman in Gold, which opens this Wednesday in New York.

The Bloch-Bauers were a wealthy, assimilated Jewish Austrian family with a reputation for supporting the arts. This was especially true of Adele Bloch-Bauer, Altmann’s childless aunt. The Bauer sisters had married the Bloch brothers, so the entire family lived together in their elegant Elisabethstrasse home during Adele’s lifetime. Sadly, Adele Bloch-Bauer died tragically prematurely from meningitis in 1925, but she would be spared the horrors that her family would face. She also made quite an impression on young Altmann, which is why her portrait meant more to the niece than its mere one hundred million dollar-plus estimated value.

For years, the Belvedere simply dubbed the painting “The Woman in Gold” to disguise its Jewish provenance, but the world knew it for what it was. Eventually, Austria announced a new restitution process, in hopes of improving its post-Waldheim image, but it was mostly just for show. Altmann and her initially reluctant lawyer Randol Schoenberg (grandson of the composer) make a good faith try to work within the Austrian legal framework, but soon find a more hospitable reception in the U.S. Federal court system. Whether or not Altmann even has standing to sue the Belvedere, an agency of a foreign government, becomes the crux of the litigation dramatized in the film.

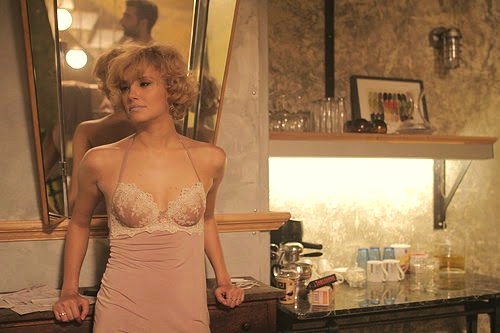

Curtis and screenwriter Alexi Kaye Campbell nicely illuminate the various legal technicalities of the case without getting bogged down in excessive detail. Curtis also juggles the 1938 Austrian timeline with the more contemporary legal drama rather adroitly. He was particularly fortunate to find such a convincing younger analog for Dame Helen Mirren in Orphan Black’s Tatiana Maslany, who grew up listening to her German language speaking parents in their Canadian household.

Of course, Dame Helen dominates the film and she is terrific as usual. She projects Altmann’s regal bearing as well as her no-nonsense pragmatism. While Schoenberg’s character is somewhat underwritten in the first two acts, Ryan Reynolds capitalizes on some crucial humanizing moments down the stretch. He gives some bite to what might otherwise been a relatively milquetoast role.

On the other hand, Katie Holmes really has nothing interesting to do as Schoenberg’s wife, Pam—and never elevates the thankless part either. However, Jonathan Pryce absolutely kills it in his too brief scene as Chief Justice William Rehnquist, portraying the jurist as quite a witty and gracious gentleman, which is rather sporting of the film, considering he ruled against Altmann in his dissent.

With Gold, Curtis does justice to a fascinating story with far reaching political and cultural implications. He helms with a sensitive hand, while maintaining a healthy pace. Frankly, it represents a marked improvement over My Week with Marilyn, which always seemed to focus on the blandest actor in any given scene. That never happens in a Dame Helen film. Still, the documentary The Rape of Europa remains the most authoritative and comprehensive cinematic word on the disputed ownership of Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer and the systematic National Socialist looting of Jewish property in general (catch up with it now, if you haven’t already). Highly recommended (in its own right) for general audiences, Woman in Gold opens nationwide this Wednesday (4/1), including the venerable single-screen Paris Theatre in New York.

LFM GRADE: B+

Posted on March 31st, 2015 at 3:34pm.