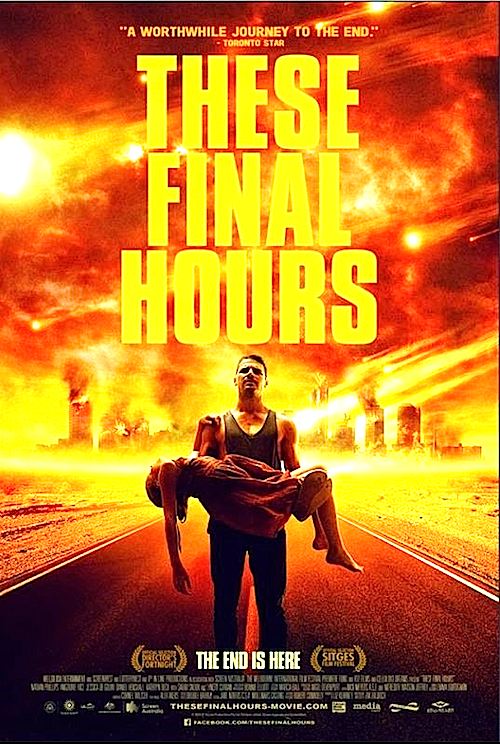

By Joe Bendel. James has mainly gone through life as a surly, self-absorbed slacker, but he is turning over a new leaf. Frankly, his efforts to reform his worthless life come in just under the wire. However, they still count for a lot in Zak Hilditch’s doomsday drama, These Final Hours, which opens today in New York.

The comet or whatever it was originally impacted in the North Atlantic. Western Europe was wiped out first and New York soon followed. We were probably fortunate in that respect. The apocalyptic shockwaves rippling across the globe will reach Western Australia last, giving the citizens of Perth enough time to anticipate the wrath about to hit them. They will deal with it in very different ways.

The immature James is determined to meet his end in a state of debauched delirium, so he leaves the lover he is with to join his even shallower girlfriend at a hedonistic end of the world party. In doing so, he fully realizes he is leaving the woman he always should have been with, in favor of the profoundly wrong one. Yet, fate intervenes when he observes two pedophiles abducting a young girl. Even after saving Rose, he is uncomfortable playing the role of her protector, but he eventually agrees to escort her to the aunt’s home where she hopes to meet up with her father. Of course, this trip becomes increasingly perilous, considering the end is nigh.

There is no doubt this particular apocalypse is a complete downer in every respect. Hilditch’s screenplay is nothing like cult favorite Night of the Comet, in which the end of the world was a total blast. Despite being a somewhat genre-ish film, TFH is emotionally heavy and deeply resonant. Yet, in a strange way it makes a hopeful statement, arguing redemption is still possible up until the very point we are engulfed in continent-buckling fireballs.

There is no doubt this particular apocalypse is a complete downer in every respect. Hilditch’s screenplay is nothing like cult favorite Night of the Comet, in which the end of the world was a total blast. Despite being a somewhat genre-ish film, TFH is emotionally heavy and deeply resonant. Yet, in a strange way it makes a hopeful statement, arguing redemption is still possible up until the very point we are engulfed in continent-buckling fireballs.

Nathan Phillips has kicked around for a while doing Australia TV and movies (such as the original Wolf Creek) and the odd Hollywood gig, but his work in TFH is next-level worthy. He convincingly establishes all of James’ considerable personality flaws, but he soon takes us to some genuinely raw and cathartic places. For the most part, Angourie Rice is respectable child thespian, but the character of Rose is problematically passive at times, like a garden variety horror movie child-in-jeopardy. On the other hand, Lynette Curran’s scenes with Phillips as James’ semi-estranged mother pack a real punch.

This is sort of film that does the little things right, such as the unseen David Field, who sets the perfect tone with some of the best voiceovers of the year as the intrepid radio broadcaster. Hilditch and his SFX team also pull off a fitting finale that feels appropriately all-encompassing without looking excessively 1990s Roland Emmerichian. This is a very well-crafted film that should generate positive attention for all involved, but you might want to follow it up with something more upbeat, like Comet. Recommended for fans of apocalyptic cinema, These Final Days opens this Friday (3/6) in New York, at the Village East.

LFM GRADE: A-

Posted on March 6th, 2015 at 1:24pm.