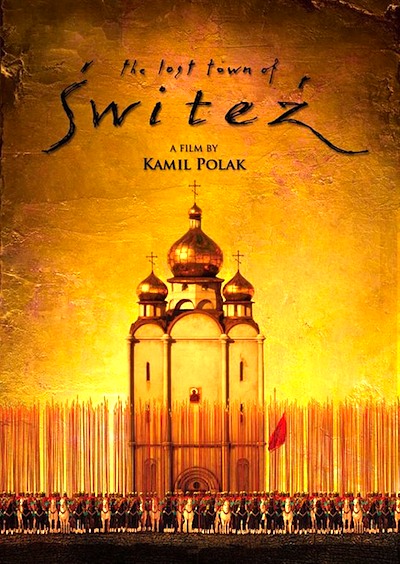

By Joe Bendel. So deeply ingrained are the images of a devastated Poland during WWII and the Soviet era, many Americans forget the millennia-old country was one of the great European powers during the Middle Ages. Poland’s Casimir III was the first crown head of Europe to grant legal protection to Jewish subjects. It was also one of the few European countries untouched by the Black Death, perhaps the result of good national karma. The glory of Medieval Poland is evoked in Kamil Polak’s visually arresting animated short The Lost Town of Świteź (trailer above), which screens this Saturday as part of the shorts program during the Film Society of Lincoln Center’s Transitions retrospective of recent Polish cinema.

Based on Adam Mickiewicz’s epic poem, one of many celebrating Poland’s folklore, Town begins on the proverbial dark and stormy night. A nineteenth century nobleman’s carriage is waylaid by the inclement weather. Far from a sanctuary, this forest appears to be enchanted. Seeking refuge from spectral horse-soldiers, the man finds himself transported to the mythic city of Świteź, where he witnesses its destruction at the hands of the hordes pursuing him. As the city faithful send up orisons to heaven, a choir of angels comes down to bear witness to man’s carnage (and perhaps the salvation of the next life).

Based on Adam Mickiewicz’s epic poem, one of many celebrating Poland’s folklore, Town begins on the proverbial dark and stormy night. A nineteenth century nobleman’s carriage is waylaid by the inclement weather. Far from a sanctuary, this forest appears to be enchanted. Seeking refuge from spectral horse-soldiers, the man finds himself transported to the mythic city of Świteź, where he witnesses its destruction at the hands of the hordes pursuing him. As the city faithful send up orisons to heaven, a choir of angels comes down to bear witness to man’s carnage (and perhaps the salvation of the next life).

Combining specially commissioned oil paintings, rendered in a style suggestive of great Polish artists like Józef Chełmoński and Aleksander Gierymski, with state of the art computer animation, Town has a rich, ethereal look unlike any in recent animation. Some enterprising film festival ought to program it with Lech Majewski’s The Mill and the Cross, which in many ways is the nearest comparable film.

Perhaps though, what is most striking about Town is the unapologetically powerful Christian imagery. Completely without irony, Polak’s film conveys an apocalyptic Christian vision with far greater overwhelming immediacy than anything attempted in recent evangelical cinema. Yet it can also be enjoyed simply as a Slavonic variant on the Atlantis archetype. The film is also perfectly scored by Irina Bogdanovich, whose compositions unambiguously suggest the Middle Ages, but with a hint of romanticism.

Town truly proves animation can be both a form of entertainment as well as high art. Best appreciated on the big screen, Polak will present his painterly canvas in-person when Town screens this Saturday (9/10) at the Walter Reade Theater, as part of Transition’s shorts block. It will also screen again in New York later in the month (9/23) at the 2011 NYC Short Film Festival as part of program A.

Posted on September 8th, 2011 at 3:02pm.