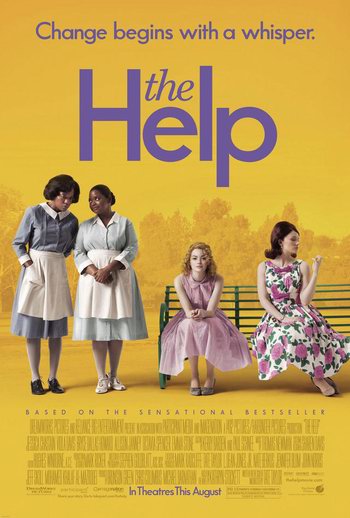

By Govindini Murty. The Help has been a truly surprising hit this summer. In a season full of alien invaders and spandex-clad superheroes, audiences are flocking to see a female-driven domestic melodrama. Based on Katherine Stockett’s best-selling novel (with over five million copies sold to date), The Help dramatizes the plight of black maids working for white families in the racially divided society of early ’60s Mississippi. The film features engaging performances from a talented cast that includes Viola Davis, Octavia Spencer, Emma Stone, Allison Janney, Jessica Chastain, and Cicely Tyson. What truly makes the film appealing, though, is its heartfelt, optimistic spirit, which ultimately suggests that reconciliation is possible even in the midst of the worst racial intolerance.

The Help is a welcome real-world antidote to the extravagant CGI fantasy films of this summer. It may not depict earth-shaking cataclysms, but the real life injustice the film depicts is just as consequential. The Help shows what happens when people allow themselves to be co-opted by group pressure into acting in inhuman ways. The white women in The Help may not all be naturally evil, but through social pressure they acquiesce to evil behavior. Their weakness, malice, and cowardice is motivated by the most mundane of reasons: the desire to be included in a bridge party, to get a medal from a women’s organization, to have the best dress or the best cook in town. Yet the decisions they make have a catastrophic effect on their fellow black citizens, depriving them of their civil rights, their livelihoods, their dignity, and even their families and their freedom.

The Help centers on the story of Eugenia “Skeeter” Phelan (Emma Stone), a well-to-do white girl who returns home to Jackson, Mississippi after graduating from college. Unlike her childhood friends who have gotten married and had children, Skeeter dreams of pursuing a career as a writer. She’s applied for a job as an editor at Harper & Row in New York, but when she’s turned down, Skeeter interviews at the local newspaper and is assigned the task of ghost-writing a house-cleaning column. Skeeter’s desire to write bewilders her mother and her friends, all of whom are apparently satisfied with their lives as decorative society wives. Skeeter’s wish to have her own career is one of the most appealing aspects of the film, one that pretty much any woman can identify with. It doesn’t hurt that the New York publishing world is depicted in such a glamorous way in the film, with the editor Skeeter writes to, Elain Stein (Mary Steenburgen), living a life of independence with a fabulous office and apartment, dressed in sleek black cocktail dresses and surrounded by handsome, well-tailored young men.

In any case, since Skeeter knows nothing about housecleaning, she turns for advice to the black maids who work for her friends. Skeeter starts talking to Abileen Clark (Viola Davis) and then meets Abileen’s best friend Minnie Jackson (Octavia Spencer). As Skeeter gets to know the maids, she witnesses first-hand the humiliating way they are are treated by the women who are her friends. In particular, Skeeter sees that her childhood friend Hilly Holbrook (Bryce Dallas Howard) has become a hectoring full-time racist who uses her position as head of the Junior League to bully the young women of Jackson into treating their black maids abusively. Skeeter is deeply pained by this. You see, Skeeter herself was raised by a black maid, Constantine, who was actually more of a mother to her than her own mother Charlotte. Constantine has mysteriously disappeared, and part of Skeeter’s quest to record the lives of the maids is motivated by her own wish to make sense of the central role that Constantine played in her life – and to figure out why Constantine would have left her family.

The Help thus explores the central dichotomy that faced many black women in the South when they were forced to work as maids because of a lack of any other opportunities. These hard-working and dignified women did the valuable work of raising the white children in their communities, yet were treated as third-class citizens who couldn’t sit on the same bus seats, eat in the same restaurants, drink from the same water fountains, send their children to the same schools, or walk in through the same entrance in a movie theater as the whites they had raised.

Such black women were exploited by a monopolistic white power structure in the South that apparently couldn’t survive if it allowed free competition and free enterprise in the black community. Thus, black Americans who could have succeeded on their own merits were systematically restricted to low-paying, menial labor, physically assaulted if they attempted to register to vote, denied loans to send their children to college or to start businesses, subjected to police brutality, and robbed of their constitutional rights. This was contrary to both the founding principles of America and to the Enlightenment ideals that form the backdrop of our Western political tradition. Continue reading LFM Review: The Help and The Importance of Individual Conscience

Even with his foibles and arguable failings totted up, DFW was the redeemer of his literary generation. He saved it from the humiliation of being the first generation in American history to lay nothing – not the least nosegay – on the graves of Emerson, Thoreau, and Whitman. He saved it from the gaping wound of a great naught.

Even with his foibles and arguable failings totted up, DFW was the redeemer of his literary generation. He saved it from the humiliation of being the first generation in American history to lay nothing – not the least nosegay – on the graves of Emerson, Thoreau, and Whitman. He saved it from the gaping wound of a great naught.