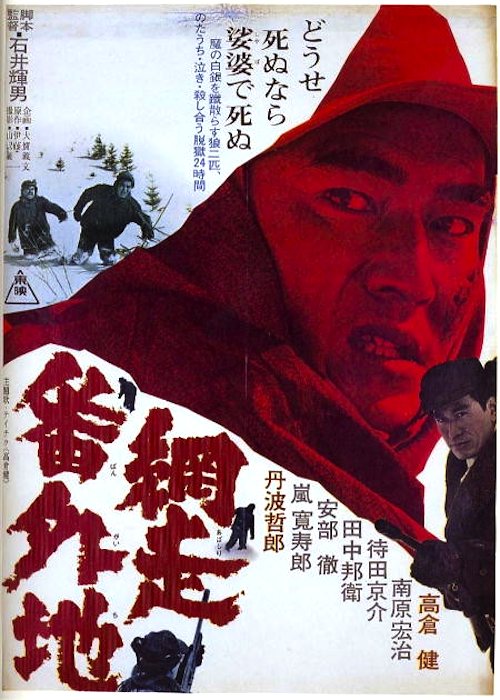

By Joe Bendel. This fortress like turn-of-the-century prison in northern Hokkaido is so harsh, it inspires country-style ballads. You can hear one right over the opening credits. Of course, it is not too tough for a hardnosed Yakuza like Shin’ichi Tachibana. However, when it comes to his mother, he turns all soft. He would like to see her again before it is too late, but the brewing prison break might not be the best way of doing that. Regardless of Tachibana’s immediate fate, lead actor Ken Takakura would soon return to the remote Hokkaido setting when his 1965 hit spawned an immensely profitable franchise. Fittingly, Teruo Ishii’s Abashiri Prison screens as part of the 2015 New York Asian Film Festival’s mini-tribute to Ken Takakura and Bunta Sugawara.

When Tachibana arrives in Abashiri, he represents the greatest challenge to the authority of Heizo Yoda, the boss of his nine-man cell. Tachibana is definitely a keeps-to-himself kind of guy, but he knows a phony blowhard when he sees one. Since he has more or less kept his nose clean, Tachibana might be eligible for parole, especially since his ailing mother is not expected to live much longer. Unfortunately, Yoda and his sociopathic running mate Gonda are plotting a cell-wide escape and they want Tachibana in on it. Naturally, they play the Yakuza loyalty card in a big way. Of course, this would irreparably cross up Tachibana’s situation. They also intend to sacrifice their elderly cellmate Torakichi Akuta in the process. Yes, you could definitely say Tachibana is facing a prisoner’s dilemma.

When Tachibana arrives in Abashiri, he represents the greatest challenge to the authority of Heizo Yoda, the boss of his nine-man cell. Tachibana is definitely a keeps-to-himself kind of guy, but he knows a phony blowhard when he sees one. Since he has more or less kept his nose clean, Tachibana might be eligible for parole, especially since his ailing mother is not expected to live much longer. Unfortunately, Yoda and his sociopathic running mate Gonda are plotting a cell-wide escape and they want Tachibana in on it. Naturally, they play the Yakuza loyalty card in a big way. Of course, this would irreparably cross up Tachibana’s situation. They also intend to sacrifice their elderly cellmate Torakichi Akuta in the process. Yes, you could definitely say Tachibana is facing a prisoner’s dilemma.

There is something very Cagney-esque about Tachibana, the sentimental Yakuza. Indeed, it is not hard to see why Abashiri launched Takakura’s career. You can see elements of plenty of previous prison genre films in it, especially when Tachibana finds himself chained to Gonda and reluctantly on the lam, as the result of some not so well thought out extemporizing. However, Ishii’s execution is lean and mean, while his cast is pitch-perfect, elevating each stock character to new tragic heights. Especially look out for Kunie Tanaka as old Akuta, because he nearly walks away with the picture in a key turning point scene.

Abashiri Prison is totally about manly men snarling at each other while freezing their manly business off. Despite a wild climax on the rail lines, it is a grungy, intimate film that is relatively narrow in scope. Ishii makes it palpably clear just how small and chilly their world has become. It is a great prison movie that will give Yakuza genre fans all sorts of happy vibes. Highly recommended for mainstream audiences as well, Abashiri Prison screens this Friday (7/3) at the Walter Reade, as part of this year’s NYAFF.

LFM GRADE: A-

Posted on July 3rd, 2015 at 12:31am.