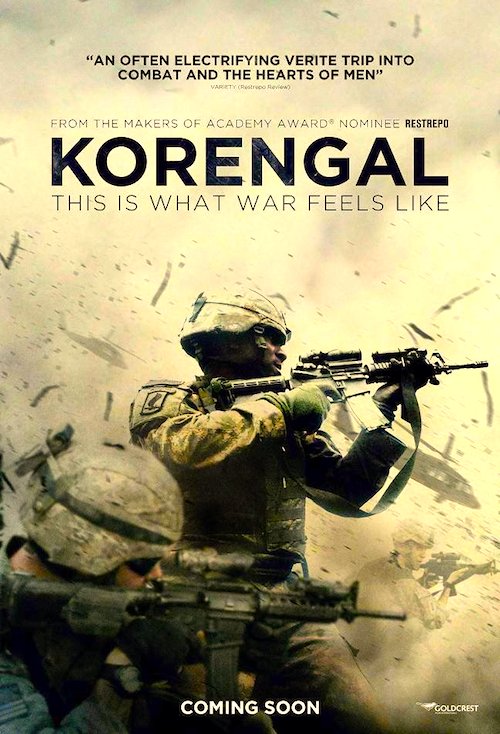

By Joe Bendel. Stationed in a remote outpost in the Korengal Valley dubbed Camp Restrepo (in honor of a late, beloved medic), the men of the Airborne Brigade’s Battle Company, 2/503 were supposed to be the tip of the spear for the American military in Afghanistan. However, in 2010, the administration decided the spear no longer needed a tip and closed all the American outposts in the deadly Korengal. Through new interviews and previously unseen footage, Sebastian Junger revisits the men featured in his Academy Award nominated documentary Restrepo, analyzing the impact of war on those who fight it in Korengal, which opens this Friday in New York.

Tragically, Junger completed Korengal without his late partner Tim Hetherington, who shot his share of the footage and served as co-director of Restrepo and the subject of Junger’s elegiac tribute documentary, Which Way is the Front Line from Here? In fact, they had always planned a more reflective companion film to Restrepo that would allow audiences to become better acquainted with the men of Battle Company.

So now that Restrepo has been decommissioned, do they miss it? More than you might think. War can be shocking and profoundly unfair, as Junger’s first film with Hetherington documents, but it can also be bracing. Nothing clears the head like a morning fire fight, especially for the athletically inclined. (In a rueful aside, one Airborne infantryman casually observes the Korengal mountain ridge would be “sports paradise” were it not for all the warfare going on.)

So now that Restrepo has been decommissioned, do they miss it? More than you might think. War can be shocking and profoundly unfair, as Junger’s first film with Hetherington documents, but it can also be bracing. Nothing clears the head like a morning fire fight, especially for the athletically inclined. (In a rueful aside, one Airborne infantryman casually observes the Korengal mountain ridge would be “sports paradise” were it not for all the warfare going on.)

However, Junger will not allow ideological viewers to conveniently dismiss the men as adrenaline junkies. That might play a part in their adaptation to the harsh duty conditions, but the men form a strong camaraderie with one another and consciously shield their loved ones from the realities of their service as best they can. They also develop unromanticized opinions of the assorted clan leaders operating within the Korengal. Frankly, they probably have a much better understanding of the country than their current civilian leadership (not that that is a particularly high standard to surpass). Indeed, they sound remarkably grounded, all things considered, despite all they have witnessed.

It is very clear why Junger made his Afghanistan films, including Front Line. They vividly capture the soldiering experience, very definitely including the sudden loss of a brother-in-arms. However, it is fair to wonder what was the purpose of the events they documented, if the strategy can be reversed at the drop of a hat? To Junger’s credit (and Hetherington’s too), the films scrupulously avoid politics, but once the house lights come back up, we exit into a political world.

Always fair to the men who appear in it, Korengal covers the full gamut of human emotions, while opening a window into one of the least forgiving corners of the world. Recommended for general audiences, perhaps even more highly than Restrepo, Korengal opens this Friday (5/30) in New York at the Landmark Sunshine.

LFM GRADE: A-

Posted on May 27th, 2014 at 2:03pm.