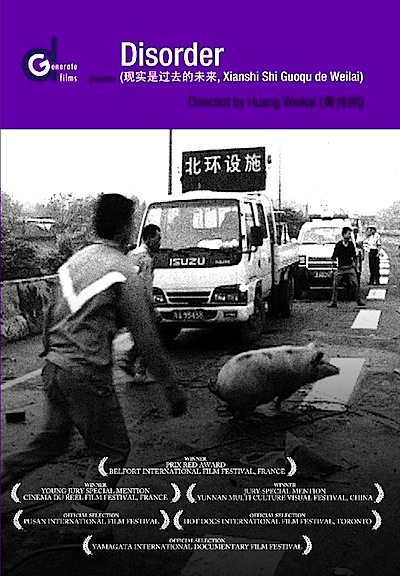

By Joe Bendel. Word to the wise, take care crossing the streets of Guangzhou and the surrounding suburbs. If you are hit by a car, the driver might just try to stuff some cash in your pocket and toss you out of the way. For their part, the police appear woefully inadequate at managing accidents. It is all rather messy and unfortunate, but it’s easy to understand how such episodes caught the attention of scores of Chinese digital video enthusiasts, whose most “youtube-able” footage has been edited together in Huang Weikai’s collage-like Disorder, which screens during the 2011 Documentary Fortnight now underway at MoMA.

China has a reputation for being a tightly regulated society, perhaps tragically so. However, the amateur video assembled by editor-director (emphasis on editor) Huang paints a more anarchic picture. At times, it is somewhat amusing. The face of a restaurant customer finding a roach in his ramen is pure movie gold. Indeed, there are plenty of “you-don’t-see-that-everyday” moments in Disorder, as when a group of men try to corral a pack of panicky pigs on the highway – while the cops watch disinterestedly. They do that quite frequently in Disorder.

China has a reputation for being a tightly regulated society, perhaps tragically so. However, the amateur video assembled by editor-director (emphasis on editor) Huang paints a more anarchic picture. At times, it is somewhat amusing. The face of a restaurant customer finding a roach in his ramen is pure movie gold. Indeed, there are plenty of “you-don’t-see-that-everyday” moments in Disorder, as when a group of men try to corral a pack of panicky pigs on the highway – while the cops watch disinterestedly. They do that quite frequently in Disorder.

However, Disorder is not all light-hearted corruption and incompetence. There is real tragedy as well. Frankly, Huang somewhat downplays the most shocking incident, most likely a by-product of China’s strict one-child policy. Still, his concluding sequences logically have the most political bite, capturing full-scale police brutality in an incident that teeters on the brink of a legitimate riot.

They might be so-called amateurs, but the videographers who recorded these scenes deserve considerable credit for standing their ground and getting their shots. In his editorial judgment, Huang demonstrates a shrewd eye for visuals and a subversive sensibility. Whether he intended to or not, he conveys a sense of the anger and frustration bubbling beneath the surface of many average citizens. Yet they never seem to release it in a coordinated, efficacious manner, as the audience witnesses in graphic terms.

At just about an hour’s running time, Disorder is a particularly manageable dose of the Digital Generation-style of independent Chinese filmmaking, appropriately distributed by dGenerate Films, the Chinese indie specialists. Short but sometimes shocking, it is a strong selection for this year’s Documentary Fortnight. It screens again tomorrow (2/20) as the annual doc festival continues at MoMA, and it might be a ticket in high demand. There were a few technical glitches at last night’s screening (ultimately resolved well enough), so some of the near capacity audience might be back for the second go-round.

Posted on February 19th, 2011 at 2:05pm.