By David Ross. The Obamas have invited some apparently outrageous rapper to the White House to participate in a ‘poetry reading,’ with predictable repercussions. The left-wing radio host Randi Rhodes fumes:

Look, the conservatives, if Shakespeare were alive, and he went to the White House to get, you know, some sort of a reading, they would be outraged about him – talking about killing his brother, and the father had to go, and a mother he slept with – They’d be out of their fricking minds with this. They don’t understand culture! Or literature!

Conservatives – at least the many who ridiculed this comment online – do know the difference between Shakespeare and Sophocles, and know that Oedipus killed his father and not his brother. Or is Rhodes hazily thinking of Hamlet? Who can tell?

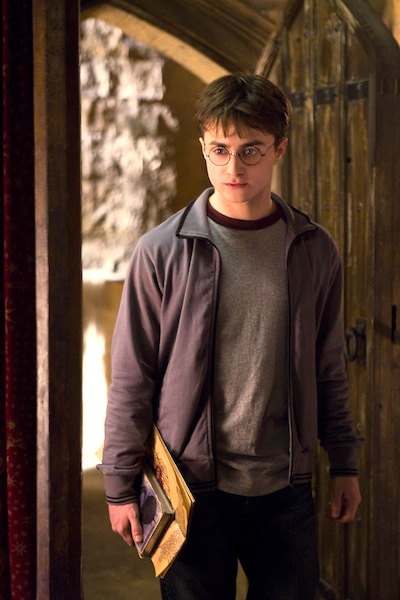

The NPR-ish notion that conservatives are sub-literate is so annoyingly counter-factual, as the central vein of Anglo-American literature for the last two hundred and more years has been essentially conservative: Swift, Burke, Coleridge, Jane Austen, Carlyle, Trollope, Thoreau, Ruskin (a self-described “violent Tory of the old school”), Yeats, Lewis, D.H. Lawrence, Pound, Eliot, Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Nabokov, Waugh, Flannery O’Connor and the Southern agrarian writers in toto, Saul Bellow. Only Dickens and possibly George Eliot, among the greatest writers, can be neatly grafted onto a liberal moral or political scheme. Even self-professed radicals, like William Morris, Virginia Woolf, and George Orwell, are only superficially or problematically so, while the elusive James Joyce is imaginable as a conservative but inconceivable – utterly self-contradictory – as a liberal of any sort. I myself consider Morris the most conservative man who ever lived and attribute his communism to a complete and rather silly misunderstanding: his communist utopia was not progressive but maniacally reactionary, a fantasy of the Middle Ages idealized and restored. Not for nothing did Yeats call Morris his “chief of men.” Some day, I believe, a scholarly fellow with a certain entrepreneurial instinct will write a fascinating book on the conservatism of Harry Potter, which borrows more than plot conventions from Tolkien and Lewis, and harks back, in its fundamentals, to the monasticism of the Middle Ages and to the legend of St. George.

In the coup de grace to the Rhodes stereotype, David Mamet, our most renowned playwright, has announced his conservative conversion with a splashy new book (see here).

In strictly political purlieus, in what are supposed to the Neanderthal caves of the right, conservatism has always been bookish. Its twentieth-century heroes – Henry Adams, Albert Jay Nock, T.S. Eliot, C.S. Lewis, Friedrich Hayek, Ayn Rand, Whittaker Chambers, Russell Kirk, Irving Kristol, William F. Buckley, Allan Bloom – were all significant men and women of letters. Even in the contemporary trenches, conservative politics remains bibliophilic. I recall a particularly asinine New York Times article that described how the Tea Party had formed a cult of Hayek, with the implication that Hayek is some sort of fringe weirdo, the half-educated Ivy League reporter apparently not understanding that he’s an Einstein-figure of world economics (speaking of whom).

Yeats, writing in 1930, theorizes the intrinsic relation between literature and the conservative sense of the world:

I would found literature on the three things which Kant thought we must postulate to make life livable – Freedom, God, Immortality. The fading of these three before “Bacon, Newton, Locke” has made literature decadent. Because Freedom is gone we have Stendhal’s “mirror dawdling down a lane”; because God has gone we have realism, the accidental, because Immortality is gone we can no longer write those tragedies which have always seemed to me alone legitimate – those that are a joy to the man who dies.

I remember, also, that Tennyson escorted George Eliot to his door and bid her adieu with the words, “I wish you luck with your atoms.” On that note, conservatism and liberalism likewise go their separate ways.

Feeling bold, one might argue that ‘liberal art’ is an oxymoron, and that liberals have produced great art only when they have temporarily transcended their own liberalism, which is to say, their faith in “Bacon, Newton, Locke.” I can think of only one great artist – Dickens – who is truly a liberal even in the moments of his greatness. As I see it, Dickens’ verbal and creative power is so fantastically hypertrophied that it largely compensates for his core shallowness (cf. Wilde’s famous quip: “One must have a heart of stone to read the death of little Nell without laughing.”).

How can it be, then, that liberals and liberalism so utterly dominate the cultural scene, from Broadway to Hollywood, while conservatives have so universally abdicated? What explains this perversion of cultural logic? The leftward trend of the arts most basically has to do with the conflation of a debased romantic pose with artistic enterprise itself. Blake, Coleridge, Shelley, Baudelaire, Rimbaud, Van Gogh, and so forth, bequeathed to us a mythos that requires the artist, heroically aflame with his own insanity, to cast himself against the prison walls of social convention and political empire. The most iconic artists of recent generations – Jackson Pollock, Marlon Brando, Allen Ginsberg, Jimi Hendrix, Jim Morrison, John Lennon, Curt Cobain – have intentionally and unintentionally affirmed this sensibility, and it has become permanently entwined with the rock’n’roll culture and its pop-cultural offshoots. All of this, of course, involves a misunderstanding. The romantics succeeded not because of but in spite of their insanities and drug addictions and half-baked radicalisms. Fundamentally they were men of enormous learning and craft. Shelley may have disseminated subversive pamphlets by hot air balloon, but he also translated Plato. Conservatives have capitulated to this misunderstanding and to their own exclusion from the creativity of the culture, and in consequence we have much self-important and tortured posturing but little real art.

Posted on May 17th, 2011 4:02pm.

I’m always amused when I argue with liberals and they discover I read, and I’m a relative literary lightweight. Honestly, it’s almost an unfair advantage because so many times they fall back on the stereotypes they themselves create and when it’s revealed that their stereotypes fall apart, so does their ability to make any argument.

But to the topic, I agree wholeheartedly. And one thing I’ve always felt is that there was a clear line between what does and doesn’t constitute art. Even if you couldn’t elaborate on why, you can clearly see that pissing on Christ isn’t art.

Excellent analysis. The only major name I would add is “Leo Strauss”–although his status as godfather to “neo-conservatism” is ridiculous–to your list of bibliophile conservatives. As a political philosopher, he explicitly recommended the study of “Great Books.”

This leads me to another consideration, namely the political problem of “conservatism.” More so than liberalism, which may be said to consist of specific dogmas, conservatism is a critical perceptive that rests on the assumption that the past is somehow greater (or nobler) than the present. For us living in the post-modern 21st century, there may be some truth to that statement. Unfortunately conservatism is ultimately a relative concept: one is only conservative to the status quo and depending on what that is our beliefs are subject to change. The American Revolution was undoubtedly fought by radicals but I would not call Washington, Jefferson, or Madison “leftists.” The same can be said for the Civil War.

All this to say that it is advisable to qualify our “conservatism”, which Yeats in your post apparently does. Although I’m unsure how the good Locke is somehow responsible for discrediting “immortality”, I would add “equality” to Yeats’ list. Not equality in the Marxist sense but in the Jeffersonian or Lincolnian sense: “All men are created equal […]” Man’s freedom is quite useless to him if he is born under a regime where his social caste determines his existence. Burke was horrified at the decapitation of Marie-Antoinette but he did not seem to mind the millions who lived in utter misery because they lacked noble blood. “A Connecticut Yankee” makes that point forcefully. In fact Mark Twain exemplifies this problem of political conservatism: although the contemporary left has largely appropriated him into their ranks, his beliefs in free-will, equality, and political liberty are complete at odds with the post-modern impulse. A 19th liberal Missourian? Yes, but there’s no American author who so completely understood and glorified the natural and universal principles of the Declaration of Independence. Nowadays the concept of natural rights is not even considered conservative but downright reactionary!

“Nowadays the concept of natural rights is not even considered conservative but downright reactionary!”

For some reason, I think that’s changing, Guillaume — at least amongst grass-roots conservatives. I’d even go so far as to say it’s a major force in the new movement.

I also think you’re on to something here: “… conservatism is a critical perceptive that rests on the assumption that the past is somehow greater (or nobler) than the present.”

The part with which I disagree is that conservatism doesn’t necessarily think the past is better, but rather we can learn from it — particularly the Founders .. American conservatism rests on this.

All this approach is saying is that if the constitutionality of something is in dispute, let’s go back and read what the Founders meant (if you haven’t already, I would rush out to read the minutes to the Constitutional Convention … they’re astounding), rather than have some left-wing activist judge do it. I believe that approach has been the greatest force in the deterioration of the U.S.

This all brings be back to the concept of natural rights. There has never — in the history of the world — been such a forward-thinking idea. Imagine … in 1776, when most civilized countries believed that God’s grace was only handed to you through a King or a Queen, a group of men said no — you are born free! Men didn’t give you rights, and men can not take them away.

THAT is what we seek to “conserve”. That is what has been taken away from us. So when my opponents tell me than my belief structure is an antiquated notion, I ask how? How can personal accountability and self-governance EVER be antiquated?

A guy I work with is a raging leftist. We both have English degrees, but he thinks I’m the biggest idiot for seeing great literary value in Ayn Rand’s works. We always have arguments based on this piece here at Libertas — fascinating.

“How can it be, then, that liberals and liberalism so utterly dominate the cultural scene, from Broadway to Hollywood, while conservatives have so universally abdicated? What explains this perversion of cultural logic?”

I’ll take a shot at this. For decades, leftists have been surgically implementing ideas of politically correctness, collectivism, and moral equivalence. It’s actually scary to read old Soviet documents that detail how to destroy American culture. The book “The Black Book of Communism” deals with a lot of this.

Liberalism is based on feelings, whereas conservatism is an intellectual pursuit of truth. That fact makes the thesis of this article here even more tragic — there’s simply no struggle in stories based on moral equivalence … Shakespeare mocked that type of storytelling, which has to tell you something.

Real struggle, real conflict is born when lines are drawn — when characters know what they have to confront. It’s also harder for the writer to achieve this, because it actually makes you work.

I just finished a novel (which I will be putting on Amazon), and I found one of the greatest challenges was to harness the narrative and make sure the conflict resonates. My main goal was to identify the story’s themes, illustrate them through motifs, imagery, and any other device I had, and — most importantly — make sure my main character didn’t turn into a naval-gazing, hand-wringing fish.

My final product — hopefully — is about maintaining faith, courage, grace, and love in the face of the most challenging situation a human can imagine.

“Liberalism is based on feelings, whereas conservatism is an intellectual pursuit of truth. That fact makes the thesis of this article here even more tragic — there’s simply no struggle in stories based on moral equivalence.”

Exactly. That’s one reason why movies and literature, the modern relativist stuff, are so lackluster. Narrative power rests on a disruption of the moral order and its consequences. If there is no morality, no story.

What you are missing as to why the liberal/left point of view has prevailed in literature is that the government leftists fund, pay, encourage, grant and basically purchase writers by the job lot. Leftists have found out how to insert probiscus into the body politic and siphon off taxpayer money. Lots of it.

But haven’t conservatives brought this on themselves to a certain degree? Who routinely bans books like Harry Potter, promotes creationism over evolution, and celebrates brawniness over brains? Plain talkin’ and beer drinkin’ as opposed to effete wine sipping? Current (incredibly popular) conservative pundits routinely mock intellectuals. When William F. Buckley died there went conservative’s open embrace of intellectuals. (although George Will is trying his best) I think to some degree the very definition of conservatism suggests sticking to the old ways, not forging innovative paths in art and letters, and too many conservatives not only accept but embrace this notion in practice.

I’d like to jump in here on David’s post and say, M, that I completely agree with your point. Buckley (and also Reagan) initially inspired my interest in conservatism, and things have changed so dramatically within the movement since his heyday. Buckley today would likely be run out on a rail from the conservative movement, would never get a gig on Fox News or on talk radio, and would probably be ridiculed by certain conservative media personalities as an ‘elitist.’

This is reasonable in its way, but it runs the danger of slipping into the same Randi Rhodes type of cliche. Do conservatives really celebrate “brawniness over brains”? The writers on this site have, between them, four Yale degrees and a couple of top-flight Ph.Ds. Are we not conservatives?

Conservatives have always embraced the past as a spiritual and cultural reference point, but they have by no means slavishly adhered to its forms. Think again of Yeats, Pound, Eliot, and Wyndham Lewis, who represented the twentieth-century’s most militant and successful avant-garde.

I have never watched Glenn Beck or anyone of his ilk, as I have no cable and could not care less anyway, but the contemporary pundits I do follow — Mark Steyn, Charles Krauthammer, Terry Teachout, Christopher Hitchens — are writers of enormous erudition. Krauthammer is not only a political pundit but a psychiatrist.

There is entire universe of conservative intellectualism that you many not have noticed. I suggest you consult Commentary and the City Journal for starters:

http://www.commentarymagazine.com/

http://city-journal.org/

All of this being said, conservatives must indeed do more to involve themselves in the culture. Conservative talk radio is a start, but along the same lines we need alternative universities, publishers (more of them), theater companies, and movie studios. The goal is not to push some narrow conservative political agenda, but to reopen the field of cultural expression in a general way and to restore an inquisitive humanism. This site, I hope, is part of that movement.

David, I’m certainly not claiming those with degrees can’t be conservative, but you can’t look at conservative culture today and say it’s embracing a life of the mind and academia. This site has a piece on Larry the Cable Guy–do you think more conservatives feel he represents them, or does David Mamet? And c’mon–many conservatives feel the cultural goal is _precisely_ to push a political agenda, IMHO. Look at Republican politicians of the last, what, 15 years? They all tout their hardscrabble early jobs and blue collar upbringing–_never_ their college and advanced degrees. The current bogeymen of the right, after terrorists, are TEACHERS, for God’s sakes.

My point is that we’re conservatives and we’re embracing the life of the mind and there are many more like us out there. The anti-intellectualism canard collapses once you pierce the MSM-cliches. Conservatism is as much a phenomenon of the library stacks as the pick-up truck. The liberal media prefers the pick-up truck narrative, of course.

I honestly don’t know who Larry the Cable Guy is. Movie? TV show? No idea.

I should have added to my list Victor Davis Hanson, a professor of classics at Cal. State, and a brilliant commentator.

http://www.victorhanson.com/

There’s no lack of thought on the right. What there may be is lack of recognition of this thought on the left and in the mainstream media.

You mentioned George Will. I liked his book on baseball (Men at Work), but otherwise I find him ponderous and predictable and a bit posturing with his professorial bow-tie. He doesn’t impress me.

In any case, thanks for your comments. I’m glad to have critical readers like yourself.

David, I would only disagree that what M is expressing here is an “anti-intellectualism canard” driven by major media. I must personally confess to being underwhelmed by what passes for today’s conservative ‘intellectual elite’ – who, whatever their virtues, are in any case unable to compete with the megawatt noise generated by talk radio and certain cable news personalities. The era of Buckley and Chambers is, alas, very much gone.

Someone pointed out to me that Auden was pretty conservative, too, seeing the world as split between the Arcadians and Utopians, as in Vespers.

In my Eden a person who dislikes Bellini has the

good manners not to get born: in his New

Jerusalem a person who dislikes work will be very sorry

he was born.

Which Bellini do you mean? The painter or the composer? I have a feeling that you are referring to Giovanni (the painter), but I don’t catch the allusion to “his New Jerusalem.” Does this refer to a painting? Can you explain? I’m interested.

I think he meant the composer.

I’m not an expert reader of Auden, but others say that he is contrasting his faith-based values against the techno-socialist values of some New Jerusalem here.

Coincidentally, I’ve been working precisely on Auden and the pastoral lately. His comments on the Arcadia/Utopia divide come from his Lectures on Shakespeare (not sure which play, though I seem to remember As You Like It). The relevant excerpt appears in The Pastoral Mode, ed. Bryan Loughrey, pp. 90-3.

The poem is Vespers from Horae Conanicae.

I can’t locate the article I read about it, but this one is good, too.

http://www.highbeam.com/doc/1G1-66681248.html

Sorry! I didn’t realize you were quoting Auden. Dumb of me. I get it now.

Didn’t Dos Passos wind up a conservative as well?

The basic idea, as far as I’m concerned, is that any intelligent literature or art is going to have a hefty dose of conservatism, whether or not written by conservatives. The problems today of conservatives and their relation to culture is a complex problem that can’s solely be laid at the feet of “anti-intellectual” conservatives. To a large extent they are reacting to the silly and childish iconoclasm of the leftist cultural gatekeepers, both in the “art world” and in academia. That’s no excuse to not try and get involved, but one would have to be blind to think that the “anti-intellectual” conservatives don’t have a point in their overreaction to those in the art world who, quite literally, hate their guts, and with a passion. I myself am a conservative doctoral candidate in political science, and even with that pedigree I still succumb, on occasion, to sputtering rage against the leftists in academia and Hollywood and elsewhere that could easily seem like “anti-intellectualism.”

The $60,000 question, as noted by others here, is how cheap iconoclasm and decadence became synonymous with art. I think Mr. Ross has a point when he posits that it grew from a certain etiolated conception of romanticism; to which I would add the wreckage left by the admittance of Marxism into art – meaning above all not communism per se, but the idea that the be-all and end-all of art is “social significance.”

But w/r/t the whole “The Bow and the Wound” notion of the artist as flaming madman, anyone remember Lionel Trilling’s evisceration of that thesis? I can’t recall the name of the essay, and I’m too lazy to go look it up, but it’s in that collection called “The Moral Obligation to be Intelligent,” or something like that. Trilling was a treasure.

Points well taken and well put. Thanks very much.

I can assure you that I succumb to more than “occasional” sputtering rage! This is not anti-intellectualism, but anti-anti-intellectualism. Its a reaction against the putatively intellectual but actually moronic contemporary culture of the left. I believe much of conservatism’s alleged anti-intellectualism is actually this kind of anti-anti-intellectualism.

Thanks for the reply – I should have been clearer in my post that I wasn’t addressing some oversight on your part but rather a few of the points made by some commenters above me. That is, I didn’t mean to imply that you had said conservatives have an anti-intellectual problem.

I like the way you put it: anti-anti-intellectualism.

It just seems to me like people on the left could spend some time, perhaps with the example of Christopher Lasch and Lionel Trilling (both liberals) to guide them, reflecting on the ruins they have created in the world of art. It’s easy to score points by looking down one’s nose at one’s opponents, and some of the points made may even be legitimate. But if the left wants to truly deserve its cultural hegemony, it has a lot of recovery and rebuilding to do, and getting snooty with conservatives isn’t going to aid in that – indeed, the monomaniacal desire to use all of art and all of culture as one mammoth, endlessly looping two-minutes’ hate against the right is a big part of the reason why the left has bolloxed up the culture to the degree that it has.

At any rate they can’t have it both ways. If they wish to forward the claim, as they often do, that they are the natural and actual proprietors of all real culture and art, then they have to accept that if it’s a wasteland, it’s one largely of their own making. Your post goes towards addressing why the wasteland is there – they’re conception of culture as they ascended to its throne was badly misguided. Too political, too ideological, too sociological, too Marxoid and too fundamentally un-aesthetic. (Believe me, as a rule I don’t like one-dimensionally right-wing art either – ideological art can be done well, but it takes a rare talent, like a Solzhenitsyn or an Orwell.)

So again, when we see a lot of the embarrassingly lame attempts by right-wingers to make entries into the culture, it’s largely because they’ve bought the left’s idea of what culture is – a big political war. And that’s bad, and sad, for everyone.

“If they wish to forward the claim, as they often do, that they are the natural and actual proprietors of all real culture and art, then they have to accept that if it’s a wasteland, it’s one largely of their own making.”

Seasaw, this is an extremely deft formulation. The problem is that the left does NOT recognize the contemporary culture — at least in its middle-brow and putatively high-brow manifestations — for the waste land that it is. On the contrary, the left is busy celebrating its racial and sexual inclusivity, its environmental sensitivity, its egalitarian demoticism, its triumph over bourgeois superstition, its heroic iconoclasm, etc.

The debate about the state of the culture is merely symptomatic, however. The more fundamental debate is about the nature and meaning of art itself. Is art a mode of activism — a version of whatever the New York Times is up to, with white wine available at the intermission — or is art the chronicle of the deepest self-reckoning and world-reckoning and reality-reckoning?

“So again, when we see a lot of the embarrassingly lame attempts by right-wingers to make entries into the culture, it’s largely because they’ve bought the left’s idea of what culture is – a big political war. And that’s bad, and sad, for everyone.”

This is exceedingly well put.

Let me note, by way of addendum, a few films that seem to me very great examples of conservative expression in the arts; Tarkovsky’s “Solaris,” Sukorov’s “Russian Ark,” Assayas’ “Summer Hours,” Pavil Lungin’s “The Island,” and of course “The Lives of Others.”

Conservatives should make films — make art — along these lines: supple, profound, speaking to elemental human concerns.

One more reply – this one superficial – then I’ll leave you alone:

I love all the films you mentioned, with particular emphasis on “Solaris.” I’ve recently re-watched it (twice in one night), and I’ve been talking about it non-stop since. Tarkovsky’s films (not all of them I’m in love with, but who is?) can have that effect.

I always imagined that if someone like Russell Kirk (not all of whose thought I’m in love with either) made movies, then the result would be something like Tarkovsky.

I’m a freak for classical Japanese film (my two favorite directors are Kurosawa and Ozu- and as you probably know, Kurosawa went gaga over “Solaris”), and I think most of their work has exactly what someone Allan Bloom said was all-but-impossible to have in popular art. Those two had this remarkable “founding fathers” vibe, attempting to make transcendent art about manly and family virtues in order to inspire some sort of cement into existence that could hold a ravaged postwar Japan together. Playfully, but in the spirit of Bloom, I often say Kurosawa was the Plato and Ozu the Aristotle of Showa Japan.

* BTW several of my current profs were students of Bloom. Bet you could narrow down a guess as to where I study to about three schools on that info. alone.

“All stories are conservative.” – Mark Steyn.

All stories are efforts to achieve a particular goal. All stories, attempt to achieve a unique goal as they attempt to right a particular wrong based upon a principle idea. Please tell me what principle idea/s liberals all share? Reciting John Lennon’s liberal anthem “Imagine” does not count. Conservatives by their nature attempt to conserve and attend to founding Judeo/Christian principles.

Hmmm. As a conservative, I really like this argument. There are plenty of well-read, intellectually serious conservatives, and plenty of great artists of the last two centuries (and more) who were essentially conservative in ideas and ideals.

But at the same time, I’m not really sure that you can just call great art conservative in essence or co-opt great artists as conservative when they would have rejected that claim. Ezra Pound, for instance, was an American expatriate who ended up supporting fascism–not what I would call a conservative.

I also think there are plenty of liberal intellectuals who are critical of postmodernism in the arts and rail against the lack of morality in many works while pining for the days of the old masters. While this is a somewhat fundamentally conservative activity, it does not seem to necessarily require political or social conservatism from the actor. Harold Bloom, for instance, has often criticized modern political correctness and attempted to uphold and define the literary canon, to wild applause from the rest of the literary establishment. Among film critics, most of the greats criticize postmodern nihilism and regard grand old masters like Welles, Renoir, Bergman, and Chaplin–themselves all leftists–as great artists that modern filmmakers ought to aspire to be. They regularly criticize ideologically driven movies for being liberal pap, and find themselves disgusted by films too ironically distant and cynical. I kind of think of this crowd as The New Republic liberals–socially and politically, they associate themselves with the Democratic party and other liberal intellectuals, but most of them still believe in old classically liberal ideals, or at least think they do, and wouldn’t support anything they saw as really radical.

The definition of liberal you seem to be working with is New Left-radical, which is obviously destructive and crazy, and leads to mostly weak, “shocking” art that only gains social acceptance and praise for a brief moment before disappearing into the dusts of history. It’s not that this isn’t a major strain of contemporary culture, it’s just that I think there’s plenty of people who consider themselves liberal who feel they can rightly criticize this strain from a liberal perspective, and I’m not sure why they’d be wrong.

Am I missing the point? Help me out here.

Stephanie,

You don’t miss the point at all. Your comments are entirely cogent. I agree that many Kennedy-type liberals are on the right side of things, but I also think that many such liberals suffer from a certain cognitive dissonance and have not realized — or are not willing to admit — that they are actually conservatives. Bloom is a splendid case in point.

You may be interested to know that Jason, Govindini, and I are all former students of Bloom, and his form of conservatism — such as it is — is very much our form. I believe we are all holding our breaths and waiting for a Mamet-style conversion. It’s not likely to happen, but one can hope.

In response to your final point, I would not say that I am unfairly collapsing liberalism into New Left radicalism. What’s happened is that strains of New Left radicalism have gone mainstream and now infect much of the liberal culture, including universities, schools, museums, journalism, the arts, and Hollywood. This is the central story of our time: the mainstreaming of New Left radicalism and the conflation of the radical perspective with the “cultured” perspective. I think it’s possible to criticize these developments from a liberal perspective, but this Trilling-esque liberalism is essentially vestigial. This kind of liberalism is really only conservatism in denial.

Keep in mind that conservatism is not a monolith. It has strands, nuances, competing emphases, and so forth. Conservatism is an intellectual disposition that can manifest itself in any number of policy preferences. You can be a conservative in favor of the Iraq War; you can also be a conservative against. Some things of course — Brutalist architecture, for example — are incompatible with conservatism in all its forms.