By David Ross. Nazism was history’s most despicable moral perversion and criminal conspiracy, but too often the examination of Nazism goes no farther than moral condemnation. This posture is perfectly understandable, but it does nothing to further the understanding of Nazism as a philosophy and historical development. The difficult thing is temporarily to relax the impulse to condemn and to bring a degree of detachment to the analysis of Nazism as a system of thought. As one who frequently teaches literary modernism – Yeats, Eliot, Pound, Lawrence, Wyndham Lewis – I must constantly address a certain kind of romantic conservatism, and this naturally raises questions about fascism and Nazism. I tell my students something like this: “Its not enough to call Nazism evil, though certainly it is evil. You have to consider the nature and logic of its evil. You have to engage its ideas.” At this point, I usually insert that I am myself Jewish, which lowers eyebrows somewhat. Two deeply thoughtful documentaries, one German, one American, attempt just this kind of work and make for important lessons in the history ideas.

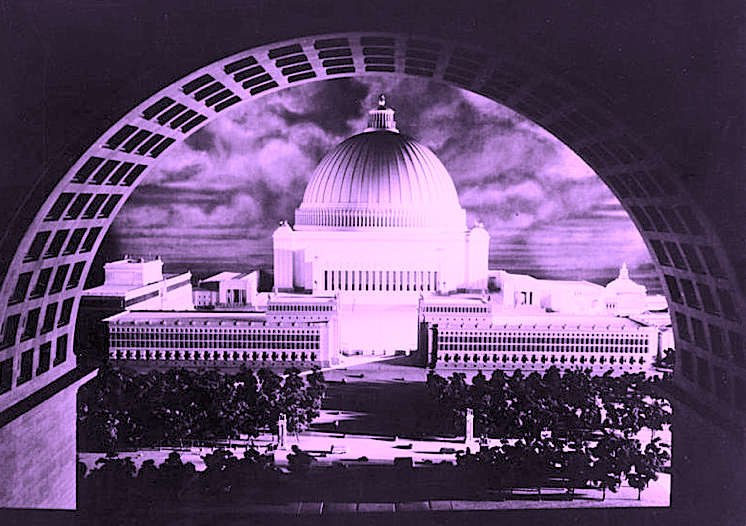

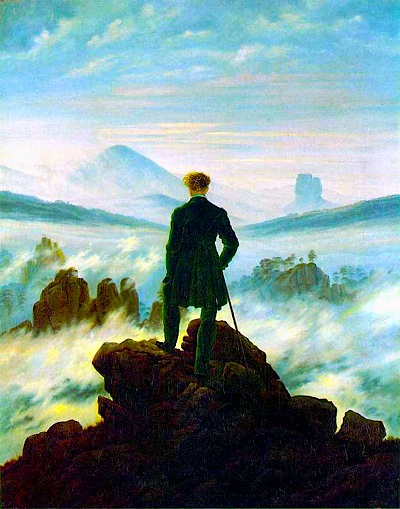

Peter Cohen’s The Architecture of Doom (1991) examines Nazi aesthetic theory and the Nazi obsession with art generally. Nazi artistic taste (a mélange of alpine-oriented romanticism and grandiose neo-classicism) was often kitschy and crass, but the Nazi cult of beauty was remarkably passionate and central. Hitler began as an artist, as everybody knows, but it’s less well known that he remained the most extraordinarily obsessed aesthete, buying and stealing works of art by the thousands and involving himself at every level with what may have been his greatest dream: the architectural recreation of Germany on a scale of classical magnificence to rival ancient Rome. The film’s crucial recognition is that Nazism’s aesthetic program partially or even largely drove its political and military program. Nazism did not conceive its program of conquest as an end in itself, but as a means of implementing the cultural and aesthetic renaissance that was Hitler’s chief fantasy. Likewise, the film clarifies the connection between Nazism’s aesthetic program and its campaign of hygiene, eugenics, euthanasia and genocide. Adulating the classical ideal suggested by the sculpture of antiquity, the Nazis conceived their murderous activities as a program of ‘beautification’ in the literal sense. The goal, according to Cohen’s film, was less to create a pure race than a physically beautiful race. The Nazis considered racial purity an indispensible basis of this beauty, but they did not necessarily consider this purity an end in itself.

This aestheticism does not in the least mitigate the Nazis’ vast crimes, but it does force us to move beyond the reassuring notion that Hitler was merely a maniacal sadist, a kind of Jeffrey Dahmer with a propaganda machine and vast army at his disposal. The scarier proposition is that aesthetic ideals we ourselves may share, or at least not entirely deplore, were mixed up in the vile stew of Nazism, and that ‘beauty’ itself may become a dangerous absolutism. Is our own culture implicated in this dynamic? Obviously we are not about to launch a racial genocide, but our popular culture may want to rethink its own extraordinary emphasis on physical perfection. Though this emphasis is not likely to lead to a renewal of the gas chambers, it may someday lead to a program of genetic selection and manipulation of the kind envisioned by a film like Gattaca. Mass-murdering the living is far worse than manipulating the unborn, but both programs share the dangerous premise that human beings are fundamentally stone to be carved, clay to be shaped. In this respect, The Architecture of Doom should give us pause.

Stephen Hicks’ Nietzsche and the Nazis (2006) delivers a whopping 166 minutes of philosophical disquisition in the attempt to explain the nature and impetus of Nazism. Unlike the graceful cinematic art of The Architecture of Doom, Nietzsche and the Nazis has the feel of a college lecture filmed on the cheap. It cuts between still photographs and Hicks himself speaking against a variety of nondescript backdrops, while the text itself is at best workmanlike. And yet Hicks, a philosopher at Rockford College in Illinois and author of a book likewise titled Nietzsche and the Nazis (2006), makes a lucid and thoroughly intelligent case that Nazism was not a function of economic conditions or social psychology or personal pathology – the usual notions – but of certain strands in the history of philosophy, and that it enacted ideas that were deeply embedded in the German culture and the German philosophic tradition. Hicks mentions Hegel, Fichte, and Marx, but gives primacy to Nietzsche, whom Hitler revered.

The question is not whether the Nazis appropriated Nietzsche – they did – but whether the Nazis accurately or inaccurately interpreted his work. On this all-important question, Hicks says that a “split decision is called for.” Hicks makes a strong case that Nietzsche was a genuine proto-Nazi (in his rebellion against the Judeo-Christian ethic of compassion, his avowal of military conflict, his embrace of the master-slave distinction, his aversion to democracy, his tendency to depose reason, his celebration of the “overman”), but he notes a number of complications that the Nazis themselves glossed over. The reverse of a German triumphalist, Nietzsche had no patience for notions of German racial superiority and was disgusted by the German character in its modern incarnation. He was particularly scathing on the subject of German anti-Semitism, which he considered a signal example of the Germans’ vulgarity and stupidity. By the same token, Nietzsche thoroughly respected Jewish intellect and racial toughness, considering the Jews superior to the Germans in these respects. Finally, Nietzsche tended to consider Judaism and Christianity equally objectionable manifestations of the “slave morality” he so much despised, while the Nazis made a sharp distinction between the two and preserved a sentimental Christianity of just the kind to disgust Nietzsche.

Hicks asks whether Nietzsche was fundamentally an individualist or collectivist. He concludes that he tended toward collectivism and thus toward the assumptions of Nazism, but this portion of Hicks’ discussion seems to me misstated. I would say that Nietzsche was in a sense both individualist and collectivist, holding that certain human beings transcend the collective, while others define it. This notion is dismaying in its own right, but it conflicts with the thoroughgoing prescriptive collectivism of Nazism, according to which all – even Hitler himself – should serve a collective interest. Hicks argues that Nietzsche considered even “higher men” mere vehicles of an impersonal, historical agency, and that they serve the impersonal end of the eventual emergence of the Overman. This interpretation is probably debatable, but in any case the mere subordination of the individual to an impersonal end is not really what we mean by collectivism. Collectivism is strictly the subordination of the individual to other people: the notion that human meaning can be fulfilled only cooperatively and in pursuit of shared purpose. In this more conventional sense, Nietzsche was not a collectivist, though he was obviously not a straightforward individualist either.

My principal objection to Hicks’ discussion, however, is its obliviousness to the enormous attitudinal discrepancy between the ironic, enormously subtle philosopher, and the semi-educated vulgarity of Nazism. Being too much the philosopher himself, Hicks does not recognize that the expression of ideas qualifies the content of ideas, and that Nietzsche’s mental suppleness in some manner complicates and even guards against the implications of his thought. Nietzsche’s ideas have a brutal thrust, but his language and manner are a constant moderating element, instantiating taste, judgment, erudition, reflection, and subtlety as informing or countervailing values. It’s not clear how Nietzsche’s complex thought might play out in an intellectually accurate social application, but very clearly Nazism was not that application. There can be no doubt that Nietzsche, had he lived to see the emergence of National Socialism, would have considered it an outbreak of intolerable boorishness and brainlessness, and that he would have considered Hitler an intellectual clown.

Does any of this exonerate Nietzsche? At the very least, he can be held accountable for failing to consider the near certainty that bumbling or pathological minds would misconstrue and misapply his ideas. To what extent is a writer responsible for his readers? To what extent must he guard against the stupidity of his readers? These are questions to which there are no easy answers, but Nietzsche, we can at least say, is the great test case.

Posted on September 26th, 2010 at 12:06pm.

The scarier proposition is that aesthetic ideals we ourselves may share, or at least not entirely deplore, were mixed up in the vile stew of Nazism, and that ‘beauty’ itself may become a dangerous absolutism.

In Peter Adams book/documentary Art in the 3rd Reich, the author mostly dismisses a theoretical National Socialist aesthetic in favor of the idea that restricting artistic expression to traditional and folk art forms was simply an Orwellian “new speak” type hijacking of German culture to the aims of the party. By definition, this is going to include a subset of our (and most everyone else’s) cultural aesthetic. This is how I see it. For one thing, it has implications for our present politically manipulative PC culture.

If you’re going to connect Nazi aesthetic theory to prior western cultural and philosophy, then that model also has to account for the remarkable similarity between Nazi art and architecture and the Communist version. IOWs, what would Engles, Marx and Lenin say about “bourgeois” art? Using the power of the state to change a people’s culture for political aims is, to my way of thinking, not an authentic cultural expression in any form. It’s a mechanistic expression of political power and may therefore theoretically belong in the realm of Nietzche for the purpose of coffee house discussion, but is more properly placed with Machiavelli in terms of history.

I really enjoy this website. Thank you.

I would re-read this post, but I do take issue with one important point you make. The “Judeo-Christian ethic of compassion” is an absurd construct. There is the Judaic ethic of compassion (or Jewish if you perfer) and the Christian ethic of compassion. By way of example, if you read the Torah you see Moses, Joshua, and the Hebrews wiped out city after city leaving no survivors – slaughtering innocent children in their cribs. That is very in keeping with Nietzsche’s “will-to-power” standard for behavior and an essential criticism of the Bible’s God. As far as the actual Christian ethic of compassion, only those willing to walk to their deaths rather than fight to defend themselves and their children rise to that standard so they are what I would call the fringe element. I paraphrase, but Nietzsche, who admired Jesus according to my recollection, wrote: “There was only one Christian and he died on the cross.”

I would contradict you to this degree. Nietzsche had contempt for undue compassion, i.e., that which enslaves an individual or a society.

‘Enthusiastic Fan,’ you are running up quite close to anti-Semitism in your remarks there. Would you care to rephrase your comments? Or at least clarify them? Is your point that Jews are incapable of compassion? I certainly hope that’s not what you’re suggesting, because you’ll be earning yourself a fast ticket off this site if you are.

Have not seen Nietzsche and the Nazis but find The Architecture of Doom very enlightening. You may find this documentary I made in graduate school to be of interest:

http://www.vimeo.com/12393284

Individual Jews, here meant those who identify themselves as Jewish, are wonderfully compassionate.

Moreover, individual Christians have commited genocide.

But Moses, Joshua, and the Hebrews commited genocide again and again. That is a fact derived from their own scripture.

My point is to indentify a fact that distinguishes Judaism from Christianity effectively. The former includes the capacity for absolute warfare including the extermination of it’s enemies. It’s an uncomfortable fact for Jews, but it is a fact. Iti not anti-Semitic and it is not even criticism here written, but information meant to point out that the term “Judeo-Christian ethic” is incorrect, misleading, and absurd. The latter requires (depending on interpretation) a self-sacrificing pacifism. Those are facts and there is not one word that in in appropriate in the above. To accuse me of impropriety would be like accusing someone of writing the history of the Inquisition of being anti-Christian.

What I wrote is not “close to anti-Semitism.” Rather what you wrote is innocently deceptive. You would make Judaism something it is not, a religion of peace. This is not a criticism of Judaism, but an informed understanding of it.

I invite you to clarify yourself would you identify one incorrect or unfair word I’ve written. Rather you ought to clarify yourself for incorrectly impugning the character of Friedrich Nietzsche.

For my part, I did not mean to offend (nor would I shy away from it in pursuit of the truth) and am not offended.

First of all, David Ross wrote the post – and I think he’s made his meaning clear beyond any need for any further clarification.

Secondly, you appear unaware that Judaism has evolved in rather dramatic ways since the days of the Old Testament – as has Christianity, as has Islam, as have Hinduism and Buddhism – and so there’s something ‘technically’ correct about what you’re saying with respect to the Judaism of thousands of years ago, while at the same time your remarks strike me as being something of an irrelevancy. We’re living in 2010, not 5000 B.C.

And also, may I be blunt? Your remarks on ‘impugning the character of Friedrich Nietzsche,’ combined with your frosty attitude toward Judaism, is sort of creeping me out here.

You are wonderfully forthright. Thank you. Also, I am grateful you have permitted me to be more precise. I’m thrilled to learn where I am mistaken, so if I’m wrong I’d be pleased to know it. I’m not irrational but might tend toward hyper-precision in my studies.

Well, the evolution of Judaism, Christianity, Islam, etc., is really your opinion of the changes to broad concepts that are impossible to correctly define, right? I think humanity has changed over the millennia and in so changing so have Jews, Christians, Muslims, Buddhists, Hindus, etc. But studies show Moses is still the most revered Jewish prophet and as I’ve indicated was categorically (while not exactly) as merciless in battle as the Mongols, the Huns, the Spanish, the Nazis, and the Japanese at their worst. I don’t find anything hyper-technical about identifying that fact however disturbing it might be to anyone. Those disturbed ought to be reminded of Jewish history, I’m quite sure. And I’d gladly have this point disputed were it inaccurate. While Jews have changed, it is still the same Old Testament that rabbis and fundamentalist Jews study and invoke and meditate upon repeatedly. You’d be in difficulty to find a Jew who feels Moses (and Joshua) behaved reprehensibly by committing genocide against the Canaanites. So, I think it’s all very complicated and while individual Jews and Jewish communities have changed, the idea that Judaism has evolved is debatable. But this is not a criticism of Judaism; I merely point out that your concieved “Judeo-Christian ethic of compassion” is an absurd construct and I indicate here that Judaic ethics are as broad as humanity’s. [King David is another case in point.] More precisely, Judaism is a broad basket of various sentiments among which are the most kind and the most vicious. The later prophets, particularly Isaiah, waxed wonderfully about a charity toward one’s community and a more generous relations among the nations on the earth. And Christianity, however pacifist it’s scripture, has inspired horrible individuals to commit as vicious acts as humanity has ever commited. Islam is a warrior faith bent toward the conquest of the earth for Allah and Islam and that is that. Anyone who says different has not read the Koran. Individual Muslims might be pacifist, but that is in disregard of the Koran. I’d welcome a contradiction.

SO PLEASE NOTE, Jews, Christians, and Muslims (etc.) may be peaceful individually – that does not mean their faiths are accurately described that way.

What bothers me is the general ease with which people seem to use the term “Judeo-Christian ethic.” It renders Jesus Christ a mere addendum when in fact he was the most radical ethical revolutionary the earth has seen for which he was crucified. He advocated an extreme pacifism that departed radically from Judaism or Paganism. Returning to the point of this post I would say it was a pacifism that was too extreme for life on earth and that was Nietzsche’s point. It would render it’s adherents and their families slaves to brutes were it taken literally.

So in summary, the idea that Judaic ethics and Christian ethics are the same is wrong (in my opinion). This does not make the point that one is better than the other or that Jews and Christians are better or worse than one another. They are different faiths and different demographics (significantly, each of course rife with hypocrites) and you are free to study each to figure out how they differ (or have evolved). I think you might begin by recognizing that Judaism is not pacifist and Christianity is pacifist (however much in thought than in deed). In any case, each individual is what they are based on their actions.

And by saying Nietzsche contravened a “Judeo-Christian ethic” you indicate in your way he was a vicious man, lacking in human kindness. No and I’d like to see evidence he was in any way cruel. Specifically, I don’t think he spoke of Judaism much at all. [I do know he had a great regard for Jews.] Rather, he criticized Christianity for it’s absurd pacifism. That does not make him mean or uncharitable but a philogist who took scriptures and faiths seriously as I do and had criticisms of all faiths as I do. So I think you kind of made him seem somehow unkind in your post without basis. I recognize you wrote without intending to mischaracterize Nietzsche, of course.

Lastly, I don’t approve of Judaism. If you read the Old Testament, you’d see the God of Abraham is horrific and I find the idea that THE GOD of the universe that controls all things and is looking out only for the chosen Jews is repugnant however rationalized. But all that means is I’m not Jewish and have well-thought out reasons why. So? Is that wrong? I don’t think so. But I don’t have animosity toward the Jewish people or any ill will toward any people. I merely disagree with them.

I just think Nietzche was a great man totally misunderstood, poorly rendered, and too often slandered, by the 21st century who strove for social justice – actually. I’d be thrilled for someone to post something that indicates otherwise.

Anyone who cares to correct me you’d be doing me a favor. But please don’t delete this without explaining to me why.

Thanks.