By Patricia Ducey. Miral, the latest from painter turned filmmaker Julian Schnabel, strives to marry lyricism to polemic; the clumsy union fails.Written by Schnabel’s collaborator and now girlfriend Rula Jebreal from her “fictionalized autobiography,” the resulting, uneven film has been soundly rejected by both critics and audiences alike. Schnabel’s prior efforts–The Diving Bell and the Butterfly, Before Night Falls, and Basquiat–chose real artists as their subjects and these unique stories, told with his exquisite painterly vision, proved eminently watchable and thoroughly satisfying as stories. Schnabel knows the territory of artist versus society, artist versus himself, and of the ecstatic vision that can sometimes destroy–he inhabits this milieu himself. He fancies himself a bit of an artistic rebel as well, clad always in his silk pajamas, carrying on his serial marriages in the NY gossip columns, all with a carefully calibrated dash of épater la bourgeoisie. Why then veer away from this successful, tragic-Romantic vein and choose the highly politicized Israeli-Palestinian conflict instead?

By Patricia Ducey. Miral, the latest from painter turned filmmaker Julian Schnabel, strives to marry lyricism to polemic; the clumsy union fails.Written by Schnabel’s collaborator and now girlfriend Rula Jebreal from her “fictionalized autobiography,” the resulting, uneven film has been soundly rejected by both critics and audiences alike. Schnabel’s prior efforts–The Diving Bell and the Butterfly, Before Night Falls, and Basquiat–chose real artists as their subjects and these unique stories, told with his exquisite painterly vision, proved eminently watchable and thoroughly satisfying as stories. Schnabel knows the territory of artist versus society, artist versus himself, and of the ecstatic vision that can sometimes destroy–he inhabits this milieu himself. He fancies himself a bit of an artistic rebel as well, clad always in his silk pajamas, carrying on his serial marriages in the NY gossip columns, all with a carefully calibrated dash of épater la bourgeoisie. Why then veer away from this successful, tragic-Romantic vein and choose the highly politicized Israeli-Palestinian conflict instead?

It would be too easy to suggest that Schnabel’s love affair with the beauteous Jebreal that began with their collaboration entirely influenced his adaptation. Instead, I attribute this filmic failure to a common psychological characteristic of the left: a veneration of victimhood that surpasses real understanding or compassion.

The Germans call it Leidensneid, or an “envy of suffering.” Based on exaggerated idealism, those who have not suffered much at all feel somewhat guilty for their good fortune (as if freedom and prosperity were mere happy accidents) and almost inexplicably offer support to ideals that they would never countenance in their own life. Communism, radical Islam, fascism; all have been momentary darlings of the left. This envy of suffering propelled the German and Italian activists/terrorists of the ‘60s to identify with the Vietnamese or the PLO against the West, for instance, and culminated in Entebbe – with the end always justifying the means, however murderous. In the leftist moral universe, the losing side is always right. Thus in Miral, if Israelis are prosperous and free thinking, the poverty stricken and devout Palestinians must be their victims.

When compared to the lot of the Palestinians, Harvey Weinstein’s trials and Schnabel’s tribulations must seem minute. Producing movies is not easy, nor is managing a successful art career, but these do not hold a candle to the vicissitudes of living in Ramallah. We must tell their story! Thus, by elevating this rosy-colored “autobiography” as the story of Palestine itself, these fortunate sons reject their own fears of seeming ordinary, unthinking or even trivial.

The first half of Miral concentrates on Palestinian woman Hind Husseini, who rescues children orphaned in the civil war that began in 1948. Her orphanage still stands today, and she would have been a fine subject for a biopic. The opening scene, a Christmas celebration at the British consulate, oddly reinforces the Anglophone values enforced during the British occupation. As the multicultural group parties on (presided over by Palestinian advocate Vanessa Redgrave) we can’t help but think that the dreaded colonialism seems like the good old days. The great teacher’s dialogue too often devolves into political exposition, but hers is a story colored in grey rather than black and white.

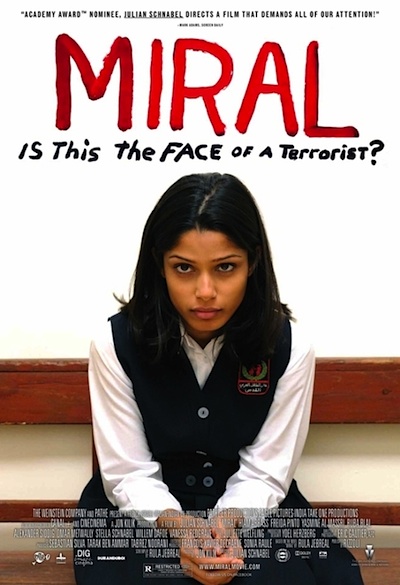

Miral’s father, a pillar-of-the-community imam (in real life, a groundskeeper) sends Miral to this orphanage after her troubled mother commits suicide. In the next scene, the story switches to Miral, now age 17, and the political story continues through the eyes of a school girl. As the intifada rages, young Miral falls in love with revolution and with a revolutionary leader. After being interrogated and beaten by the IDF, she reconsiders. She stays home to nurse her fatally ill father. She resents her brother’s Jewish girlfriend, but gets to know her and later enjoys sleepovers and rock and roll with her. The Palestinian “activists” brand her revolutionary boyfriend as a traitor for working with Israel on a two-state solution, so they murder him. Ms. Husseini eventually arranges for a scholarship, and off Miral goes to Rome to complete her education. Never do we learn what Miral thinks of all these hard life lessons or how she changes. She has no inner life; she is just a stand-in for Everywoman, Palestinian style.

The Israeli characters in the film are bigots or sadists or worse, while all the Palestinians are heroes or doomed victims. All of their violence is a reaction to Israeli oppression. Sadly, and predictably, Schnabel’s pity thus reduces them once more to subject rather than agent of their own story.

The artist Basquiat, the Elle editor Bauby in Diving Bell, the Cuban poet and novelist of Before Night Falls—all of these are individuals who suffered fates unique to each, and Schnabel illuminated them into universal stories. Miral is a composite “fictionalized” subject; she is a stand-in for the story of a collective–the ‘Palestinian,’ whatever that word means to you. Miral thus succeeds as drama or polemic about as well as The Red Detachment of Women or Reefer Madness.

[Footnote: This is interesting–my film school alma mater, Chapman Film (Dodge College of Film) built a professional style studio a few years back and has now formed its own production and distribution company, Chapman Entertainment, LLC, aiming to produce films on traditional and other platforms. Chapman alum Travis Knox (Bucket List producer) will helm production and development operations. Chapman, a private university, leans a bit right, so sharpen your pencils, writers, there’s a new playa in town!]

Posted on March 28th, 2011 at 5:38pm.

He left his Basque wife for her. I wonder if he’ll in turn leave her for an Ulster girl to complete the set?

I was really upset when I saw this trailer in the movie theater recently. With everything going on in the Middle East, I can’t believe the Weinsteins would back yet another movie that goes after Israel. Haven’t the Israeli’s been attacked enough? Why can’t there be any movies about all the terrorism that the Palestinians sponsor?

Unfortunately, the artistic community has abandoned that idea.

Patricia – thanks for another excellent review. There has been considerable controversy over the one-sided depiction of Israel in this film, especially after it was screened at the United Nations recently (a body well-known for its frequent denunciations of Israel). Julian Schnabel has responded that the film is intended to foster peace between Israelis and Palestinians, but how can any film foster peace when it unfairly portrays one side – the Israeli – as exclusively unjust and sadistic?

Thank you again for your thoughtful and articulate piece exploring this difficult issue.

It’s sadly ironic that the UN sponsored the premier of this anti-Israei film, yet they in fact “created” the state of Israel!