By Jason Apuzzo. We’re all looking for signs of hope in the Islamic world – signs of liberalization, of Westernization, of modernity seeping its way through the cracks. Some of the most hopeful signs in this regard are starting to appear in the arts – and particularly in film. Recently here at LFM we’ve talked about films like Four Lions, The Infidel, No One Knows About Persian Cats, and the striking web series Living with the Infidel (my personal favorite). These are all projects that have either received mainstream distribution, have screened to critical acclaim at festivals like Sundance and Cannes, or have in some cases – particularly Four Lions – done killer business at the indie box office. [The weekend it opened in the UK, Four Lions actually had a better per-screen average than Iron Man 2, which opened that same weekend.]

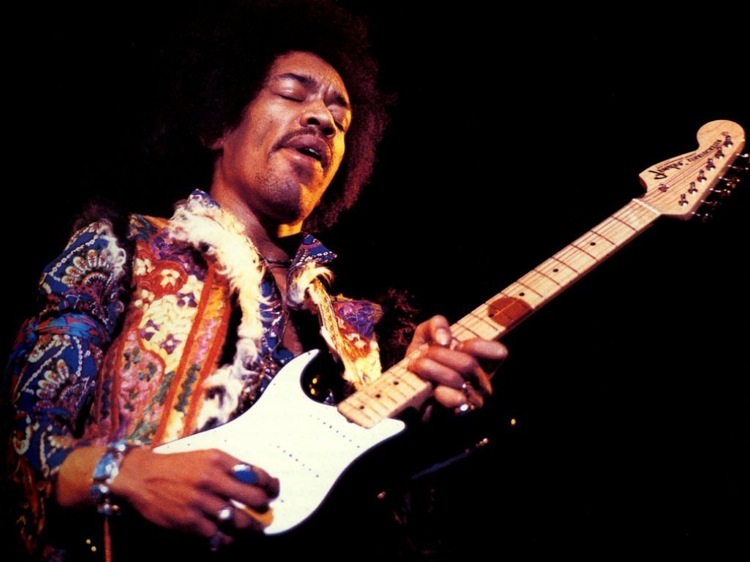

Of all these films, No One Knows About Persian Cats may have surprised me the most (see my review) – in part because it revealed how deeply Westernized today’s Iranian youth already are. I hadn’t been aware that Iran’s young people already have a sound – a kind of pop music signature – around which they are rallying against the oppressive forces of religious conformity in their society. This is an extremely encouraging sign that leads me to believe that revolutionary change is coming to Iran sooner rather than later.

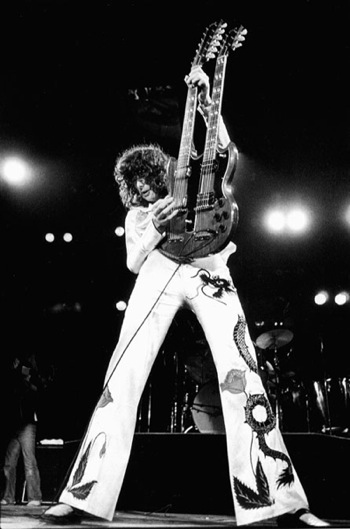

And now another new film is coming down the pike – not specifically dealing with Iran, but more generally with Islamic young people in America for whom music is their vehicle of protest. The name of this film is The Taqwacores (the title combines “taqwa” – the Arabic word for “piety” – with the English word “hardcore”). You can catch the trailer for The Taqwacores above – the film premiered at this year’s Sundance Film Festival, and also ran at the South by Southwest Festival. The Taqwacores is about an imaginary punk rock band made up of disaffected young Islamic guys in Buffalo.

And now another new film is coming down the pike – not specifically dealing with Iran, but more generally with Islamic young people in America for whom music is their vehicle of protest. The name of this film is The Taqwacores (the title combines “taqwa” – the Arabic word for “piety” – with the English word “hardcore”). You can catch the trailer for The Taqwacores above – the film premiered at this year’s Sundance Film Festival, and also ran at the South by Southwest Festival. The Taqwacores is about an imaginary punk rock band made up of disaffected young Islamic guys in Buffalo.

Does the subject matter sound obscure? It might, except for the fact that as The New York Times reports, The Taqwacores is based on a popular and influential novel – written by 32 year old Michael Muhammad Knight – that’s already become a kind of Catcher in the Rye for young American Muslims. Indeed, an entire music/youth sub-culture has apparently grown up around Knight’s novel in Islamic communities all across America – communities that are now eagerly anticipating the release of the film this autumn.

Here’s a synopsis of the film, provided by the Sundance film festival:

Yusef, a straitlaced Pakistani American college student, moves into a house with an unlikely group of Muslim misfits—skaters, skinheads, queers, and a riot grrrl in a burqa—all of whom embrace Taqwacore, the hardcore Muslim punk-rock scene. They may read the Koran and attend the mosque, but they also welcome an anarchic blend of sex, booze, and partying. As Yusef becomes more involved in Taqwacore, he finds his faith and ideology challenged by both this new subculture and his charismatic new friends, who represent different ideas of the Islamic tradition.

Just because these young Muslims embrace America’s punk-rock subculture, and reject more traditional modes of Islamic observance, don’t expect that they’re watching Fox News or attending Tea Partys. That’s not quite the vibe, if you know what I mean. It’s obvious from the reporting on this film that post-9/11 Islamophobia is a still a concern among young American Muslims, although one would hope that the election of an American President with the name ‘Barack Hussein Obama’ – with roots in the Islamic world – would have at least comforted them somewhat on this point. In any case, one senses that such anxieties will probably ease over time.

First time Director Eyad Zahra struck a very positive note in an interview he did several months ago:

Ultimately, we hope that this film can generate new kinds of discussion within America, for both non-Muslims and Muslims. This film is trying to crush all social barriers that have been thrown up in recent years. The hope is that Americans can truly see Muslims as Americans, and that Muslims can truly see themselves as American. We are tired of the ultra politically correct, sugarcoated community bridging that been going on lately, and obviously, we aren’t fans of the disgusting Islamaphobia that has been projected on the other side of the spectrum either. We want things to have more honest discussions about this kind of stuff, because that how things will really change for the better.

I think that’s just the right tone. And something that would really help matters in this regard would be if America’s more conservative-leaning media outlets would give this film a chance when it comes out this fall. Although I haven’t had the pleasure yet of seeing the film myself, The Taqwacores has gotten positive reviews, and could use the extra attention such media outlets would bring. It’s sometimes difficult to take seriously the incessant complaining about Hollywood from America’s right wing, when so little effort is ever made by them to positively promote the work of brave filmmakers who break from conventional Hollywood liberalism. We’ll see if this film gets the chance it deserves.